My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

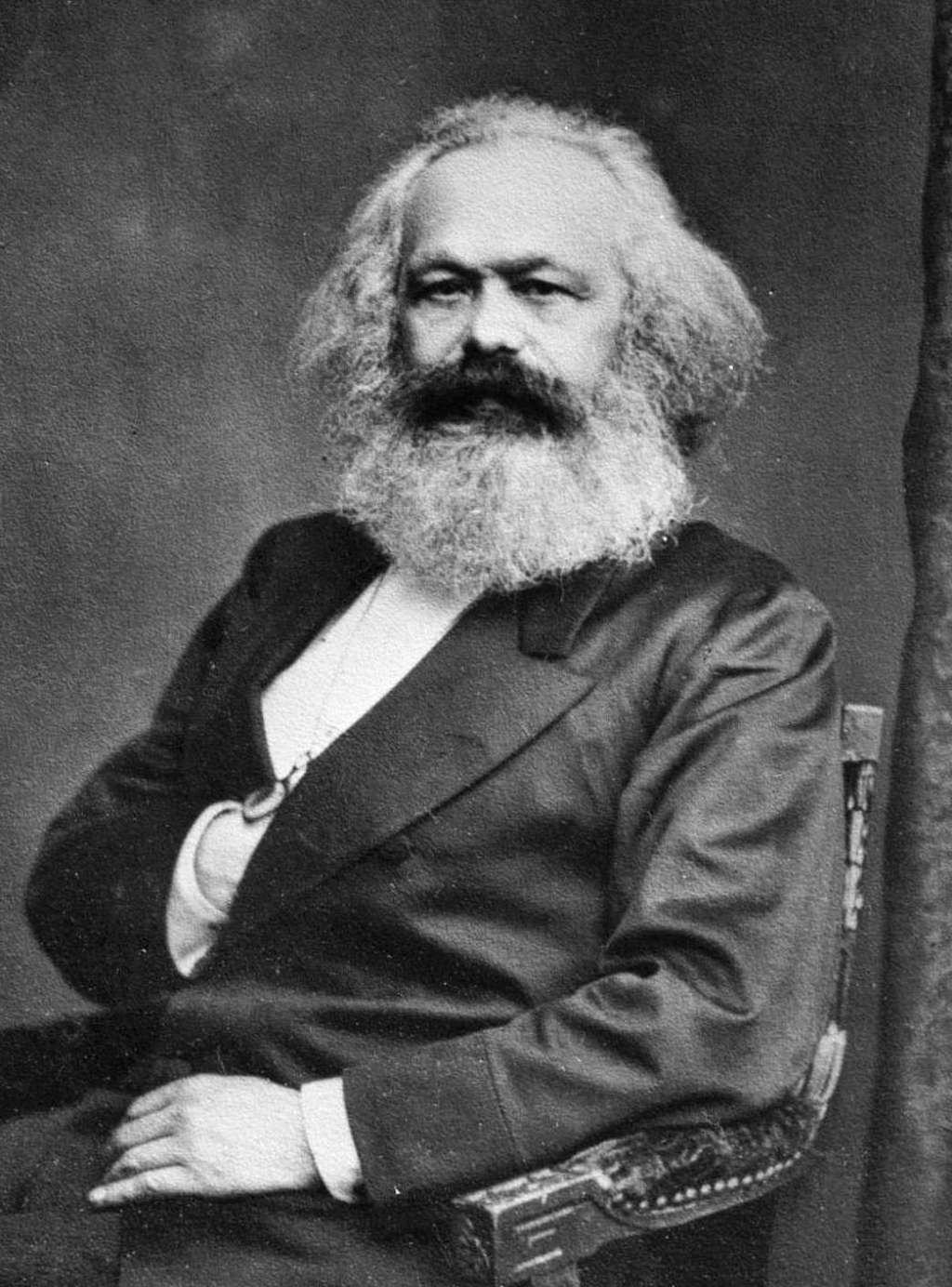

Karl Marx was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist whose ideas gave rise to the foundation of modern communism and deeply influenced critical social theory. Born in Trier in the Rhineland to a middle-class family of Jewish descent (later converted to Christianity), Marx studied law and philosophy at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. Influenced early on by Hegelian philosophy and the Young Hegelians, Marx’s intellectual journey gradually diverged toward a materialist critique of existing society, religion, and the state.

Marx’s mature thought emerged in the 1840s through close collaboration with Friedrich Engels. Their joint work, The German Ideology (written 1846, published posthumously), laid out the framework of historical materialism—the theory that material conditions and economic practices drive historical development. This period also produced the fiery polemic The Communist Manifesto (1848), written amid the revolutionary ferment across Europe. Its famous rallying cry, “Workers of the world, unite!” encapsulated Marx’s lifelong commitment to proletarian revolution.

Exiled from Germany, France, and later Belgium, Marx eventually settled in London in 1849, where he remained for the rest of his life, working in relative poverty. It was during this long exile that he undertook his magnum opus, Capital (Das Kapital), a multi-volume critique of political economy. Volume I (1867), the only volume published in his lifetime, analyzes the capitalist mode of production, especially the dynamics of surplus value, commodity fetishism, and exploitation. Engels later edited and published Volumes II and III posthumously, based on Marx’s extensive notes.

Marx’s approach to theory was not academic in the conventional sense but revolutionary. He insisted on the unity of theory and praxis—“The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” His economic theory, while deeply grounded in classical economics (notably Adam Smith and David Ricardo), departed fundamentally by foregrounding labor exploitation and class antagonism as the engine of historical change. Marxism, as later theorized, combines his contributions to philosophy (especially dialectical and historical materialism), political science (class struggle, revolution), and economics (value theory, crisis theory).

Marx was also a journalist and political organizer, playing a key role in the International Workingmen’s Association (First International). Though plagued by illness and hardship in his later years, his intellectual productivity remained high, and his legacy endured through revolutionary movements, from the Russian Revolution to global anti-colonial struggles, and remains influential in academic disciplines including sociology, critical theory, and political philosophy.

Influence and Legacy

Marx’s thought formed the cornerstone of Marxist theory and had a seismic impact on 20th-century history, from Leninism and Maoism to the Frankfurt School and contemporary critical theory. His influence stretches across disciplines, from anthropology and historiography to art criticism and literary theory. Scholars continue to debate and reinterpret his ideas in light of global capitalism, environmental crisis, and digital labor in the 21st century.

His grave in Highgate Cemetery, London, bears the inscription: “Workers of all lands unite” and “The philosophers have only interpreted the world—the point is to change it.”

Select Bibliography

Primary Sources (by Marx):

• Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I. Translated by Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin Classics, 1990.

• Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. Edited with an introduction by Gareth Stedman Jones. London: Penguin Classics, 2002.

• Marx, Karl. The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. In Political Writings, Vol. 2, edited by David Fernbach. London: Verso, 2010.

• Marx, Karl. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Martin Nicolaus. London: Penguin Books, 1973.

• Marx, Karl. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Translated by Martin Milligan. New York: Prometheus Books, 1988.

Secondary Sources:

• McLellan, David. Karl Marx: A Biography. 4th ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

• Wheen, Francis. Karl Marx: A Life. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

• Harvey, David. A Companion to Marx’s Capital. London: Verso, 2010.

• Stedman Jones, Gareth. Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2016.

• Mandel, Ernest. The Formation of the Economic Thought of Karl Marx. London: Verso, 2015.

Leave a comment