My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

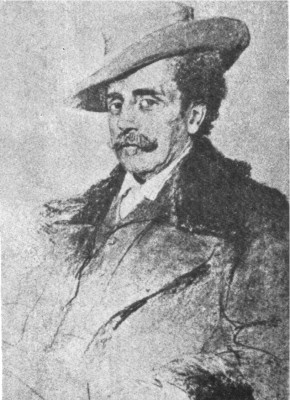

Antonio Labriola stands at the point of origin for an autonomous, philosophically serious Marxism in Italy. Trained within the currents of post-Hegelian Italian philosophy, he became—without ever becoming a party functionary—the country’s first systematic expositor of historical materialism and one of its most acute critics of positivist “economism.” Teaching at the University of Rome from 1874 until his death in 1904, Labriola forged a distinctive reading of Marx that would decisively shape the generation of Benedetto Croce and, later, the revolutionary problematic of Antonio Gramsci.

Born in Cassino (then San Germano) on July 2, 1843, Labriola’s early philosophical itinerary passed through the Italian Hegelian milieu (notably the circle of Bertrando Spaventa) before he settled into academic life in Rome. His university lectures moved from ethics and pedagogy to the philosophy of history; the decisive turn to Marx came in the 1890s amid Italy’s social conflicts and the consolidation of the Socialist Party. Even then, Labriola remained an intellectual independent, engaging socialist militants and public debates but pursuing Marxism primarily as a scientific and critical method rather than as a closed doctrine.

Historical Materialism as Critical Method

Labriola’s central contribution was to insist that Marxism is not a metaphysical “philosophy of history,” but a critical, historical science of social formations. In a series of essays—In memoria del Manifesto dei comunisti (1895), Saggi sulla concezione materialistica della storia (1896–97), and Discorrendo di socialismo e di filosofia (1897)—he argued that historical materialism explains how forms of life (productive forces, relations of production, institutions, ideologies) are made and unmade through human practice. Against both crude determinism and abstract idealism, Labriola emphasized the category of praxis: history as the product of collective activity under determinate material constraints. This insistence on praxis became a signature of Italian Marxism, later re-elaborated by Gramsci as the filosofia della prassi.

Labriola was particularly alert to the ideological misreadings of Marx current in the Second International. He criticized “vulgar materialists” who dissolved class struggle into evolutionary automatism and warned against converting Marxism into a teleological panorama of world history. For Labriola, the dialectic was not a speculative schema but a method for grasping concrete totalities in motion—class conflicts, state forms, and cultural practices—without collapsing them into a monocausal economic base-superstructure caricature.

Style, Audience, and European Reception

The rhetorical style of Labriola’s essays—discursive, polemical, and pedagogical—reflected his conviction that Marxism had to be learned as a method of research and political education. His works circulated widely beyond Italy. The 1897 French edition of the Essais sur la conception matérialiste de l’histoire appeared with a prefatory essay by Georges Sorel, who recognized in Labriola an antidote to both “orthodox” dogma and a purely economistic socialism. Early English translations (notably those issued by Charles H. Kerr) helped form a transnational reception.

Against Colonialism and Opportunism

Situated amid Italy’s fin-de-siècle crises—agrarian unrest, the repression of the Fasci Siciliani, and the colonial disaster at Adwa—Labriola’s political writings combated both bourgeois nationalism and the temptations of socialist “ministerialism.” He identified colonial ventures as bourgeois solutions to domestic contradictions and insisted that socialism could not be a mere ameliorative program within a capitalist horizon. While he engaged party leaders tactically, his enduring stance was theoretical intransigence combined with methodological openness—a refusal of both revisionist dilution and scholastic ossification. (On the breadth of his polemics and their timing see the biographical syntheses and document archives below.)

Influence on Croce and Gramsci

Labriola’s immediate intellectual afterlife ran along two divergent tracks. For Croce, Labriola opened a path from Hegel to a historicism emancipated from positivist determinism; Croce would later move beyond Marxism, but retained Labriola’s insistence that history is made through human activity embedded in institutions and culture. For Gramsci, Labriola’s repeated description of Marxism as a philosophy of praxis was foundational: it oriented Gramsci’s analyses of hegemony, civil society, intellectuals, and the party as an “educator”—all premised on the primacy of organized collective activity that transforms both structures and subjectivities. Contemporary scholarship on the “Italian road” from Labriola to Gramsci has recovered this lineage with renewed precision.

Legacy

Labriola died in Rome on February 12, 1904. His corpus is compact but generative: a handful of essays, prelections, and letters that redirected Italian socialism toward a non-positivist, conflictual, and cultural understanding of Marxism. Across the twentieth century his writings remained a touchstone—reprinted in multiple languages and periodically rediscovered whenever Marxism sought to reassert itself as a critical method rather than a catechism. Recent reassessments emphasize precisely this: Labriola’s Marxism was an open research program anchored in praxis.

Selected Bibliography

Primary Works (originals and translations)

• Labriola, Antonio. In memoria del Manifesto dei comunisti. Rome: Loescher, 1895. (Also in Saggi sulla concezione materialistica della storia.)

• ———. Saggi sulla concezione materialistica della storia (1896–97). Paris: V. Giard & E. Brière, 1897 (French translation with Sorel’s preface: Essais sur la conception matérialiste de l’histoire).

• ———. Discorrendo di socialismo e di filosofia. Naples: Loria, 1897; later eds. Rome: Loescher, 1902.

• ———. Essays on the Materialistic Conception of History. Trans. (early English ed.) by/for Charles H. Kerr, 1908; digitized ed., Project Gutenberg, 2010.

Secondary Sources

• Britannica, “Antonio Labriola.” Concise biographical overview with dates, institutional positions, and intellectual profile.

• Croce, Benedetto. Scritti varii: editi e inediti di filosofia e politica. Bari: Laterza, 1906. (Includes early memorial/assessments of Labriola’s work and influence.)

• Dainotto, Roberto. “Antonio Labriola Knew That Marxism Was a Philosophy of Action.” Jacobin, July 30, 2023. A synthetic, contemporary reassessment of Labriola’s praxis-centered Marxism and its relation to Gramsci.

• “Antonio Labriola Archive.” Marxists Internet Archive (texts, biography, and translations). Useful primary-source hub.

• Viewpoint Magazine Editors. “Between Dialectical Materialism and Philosophy of Praxis: Gramsci and Labriola.” Viewpoint Magazine, 2016. On Labriola’s anti-deterministic reading of Marx and Gramsci’s uptake.

• Frosini, Fabio, et al. Marxism and Philosophy of Praxis. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. Traces the intellectual line from Labriola to Gramsci in Italy, 1895–1935.

• “Labriola, Antonio (1843–1904).” Encyclopedia.com. Brief scholarly reference on his teaching in Rome and role as first Italian Marxist philosopher.

• Sorel, Georges. Preface to Antonio Labriola, Essais sur la conception matérialiste de l’histoire. Paris: V. Giard & E. Brière, 1897. (Preface text available via UQAM Classiques des sciences sociales.)

Leave a comment