My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

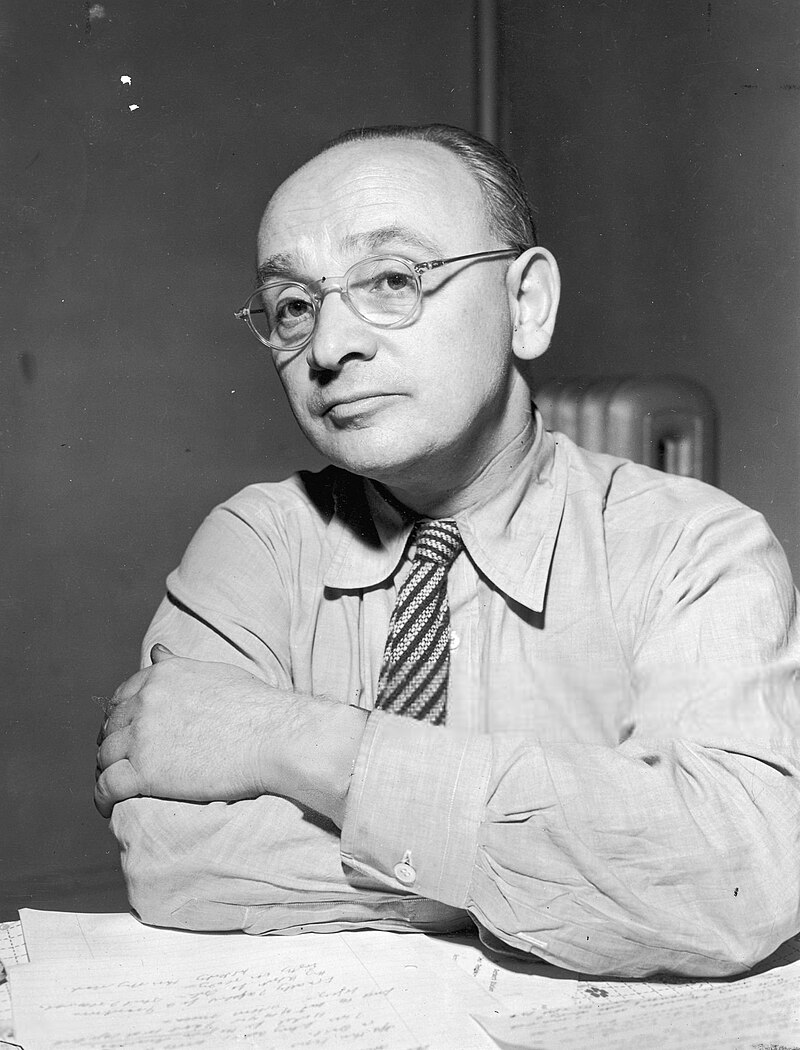

Gerhart Eisler (1897–1968) was a German communist intellectual, journalist, and political operative whose career spanned the tumultuous first half of the twentieth century—from the ideological crucible of Weimar Germany to the early Cold War confrontation between East and West. A key yet often overshadowed figure within the international communist movement, Eisler’s life reflects the contradictions, ambitions, and repressions that shaped the global Left in the twentieth century.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Born on February 20, 1897, in Leipzig, Germany, Gerhart Eisler was the son of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Eisler, a secular humanist of Jewish origin, and Ida Maria Fischer, a teacher. His siblings, the composer Hanns Eisler and the feminist writer Ruth Fischer, would also become significant figures in Marxist cultural and political life. The Eisler household, steeped in intellectual radicalism, instilled in Gerhart an early commitment to critical thought and social justice.

Eisler’s education was interrupted by World War I, during which he served in the Austro-Hungarian Army. The experience radicalized him, leading to his alignment with the revolutionary socialist movements that emerged in Central Europe following the 1917 Russian Revolution. By 1918, he had joined the Austrian Communist Party (KPÖ), becoming active in its propaganda and organizational efforts. His early writings reveal a synthesis of Marxist theory and a deep skepticism toward bourgeois liberalism—a stance that would define his political orientation for life.

Comintern Years and International Activity

In the 1920s and 1930s, Eisler became an important functionary in the Communist International (Comintern), the Moscow-based organization dedicated to coordinating revolutionary movements worldwide. He worked under various aliases—including “Hans Berger” and “Gerhart Langer”—as he carried out assignments across Europe, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

Eisler was known for his discipline, discretion, and strategic acumen—qualities that led to his appointment as a liaison between the Comintern and various national parties. In the late 1920s, he helped organize communist propaganda operations in China and later played a role in coordinating European anti-fascist efforts during the rise of Nazism. His work was shaped by the Stalinist consolidation of power within the Comintern; Eisler proved a loyal executor of Moscow’s directives, a stance that often placed him at odds with his sister Ruth Fischer, who was expelled from the German Communist Party (KPD) as a “Trotskyist deviationist.”

Eisler’s loyalty to the Soviet line during the Great Purges ensured his survival within the perilous Comintern apparatus—a testament both to his political skill and to his complicity in the bureaucratic mechanisms of Stalinism.

Exile, Imprisonment, and Flight

With the Nazi rise to power in 1933, Eisler fled Germany and lived in exile, working in various capacities for the Comintern. By the late 1930s, he was stationed in the United States, where he served as a covert political coordinator for Communist operations in the Western Hemisphere. During this period, he came under the scrutiny of U.S. authorities for alleged espionage and subversive activities.

Following World War II, as Cold War tensions intensified, Eisler became a target of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In 1947, he was arrested and charged with perjury and contempt of Congress for refusing to disclose details of his affiliations. Labelled “the No. 1 Communist in America” by the press, Eisler became emblematic of early Cold War anti-communist paranoia.

In 1949, facing renewed imprisonment, Eisler escaped aboard the Polish liner Batory and fled to East Germany via Britain and Czechoslovakia. His daring escape made international headlines and was widely seen as a propaganda victory for the socialist camp.

Later Years in East Germany

Settling in the newly formed German Democratic Republic (GDR), Eisler became a senior official within the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and played a central role in the organization of the state’s broadcasting and information apparatus. As head of Radio DDR and later chairman of the State Committee for Broadcasting, Eisler was instrumental in shaping the ideological messaging of East German media, emphasizing cultural education, socialist realism, and anti-imperialist solidarity.

Although Eisler publicly championed Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, his private correspondence reveals an increasingly disillusioned intellectual struggling with the ossification of East German socialism. His role as both a loyal servant and an uneasy critic of bureaucratic socialism mirrored the broader tensions within the GDR’s ruling elite.

Eisler died suddenly on March 21, 1968, during a diplomatic trip to Yerevan, Armenia. His death, occurring amid the upheavals of 1968, symbolized the passing of a generation of revolutionary functionaries whose lives were shaped by the paradoxes of faith and pragmatism, idealism and authoritarianism.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Gerhart Eisler’s legacy is complex and contested. To some, he was a disciplined internationalist—a committed revolutionary who devoted his life to the global struggle against fascism and capitalism. To others, he exemplified the moral compromises of Stalinist communism: a bureaucrat who subordinated ethics to ideological loyalty.

In recent scholarship, Eisler has been reassessed not simply as a political operative but as a product of the intellectual and moral dilemmas of twentieth-century Marxism. His life traces the arc from revolutionary hope to bureaucratic disillusionment, revealing how the dream of emancipation could become ensnared in the machinery of state power.

Selected Bibliography

• Bachmann, Dieter. Gerhart Eisler: Funktionär im Jahrhundert der Extreme. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 1997.

• Fischer, Ruth. Stalin and German Communism: A Study in the Origins of the State Party. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948.

• Klehr, Harvey, John Earl Haynes, and Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov. The Secret World of American Communism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

• McLellan, Josie. Antifascism and Memory in East Germany: Remembering the International Brigades, 1945–1989. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004.

• Scherstjanoi, Elke. Gerhart Eisler in Amerika: Kommunismus, Kalter Krieg und die Flucht auf der Batory. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2010.

Leave a comment