My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

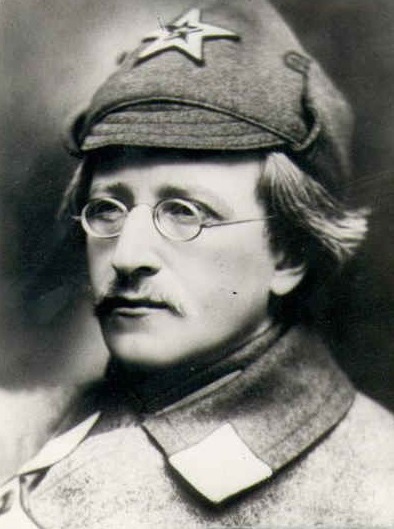

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko—soldier, Bolshevik organizer, civil-war commander, diplomat, prosecutor, and finally victim of Stalin’s Great Terror—embodied the arc of the first Soviet generation. Born in Chernihiv (Chernigov, Russian Empire) to a tsarist infantry officer, he received a military education but broke with the imperial order early: in 1901 he was expelled from the Nikolaev Military Engineering School for refusing to take the oath of allegiance, soon joining Marxist circles and the RSDLP. Through arrest, prison, and exile, he honed a profile as a militant with organizational flair and audacity, qualities that would define his role in 1917.

From 1905 to Exile

During the 1905 Revolution, Antonov-Ovseenko helped organize attempted military uprisings in Poland and at Sevastopol. Repeatedly arrested, sentenced to death (commuted to penal servitude), and famously escaping by a carefully staged ruse, he continued clandestine work before leaving Russia and participating in émigré politics. In Paris during World War I he co-edited the anti-war socialist paper Nashe Slovo with Leon Trotsky and Julius Martov, reflecting a consistent internationalist position against the imperialist conflict and a lifelong tendency to ally with the Left Opposition in intra-party disputes.

1917 and the October Insurrection

Returning to Russia after the February Revolution, Antonov-Ovseenko joined the Bolsheviks and became a key operative in Helsingfors (Helsinki), agitating among soldiers and sailors. Arrested during the July Days and imprisoned with Trotsky, he was released after Kornilov’s failed putsch and was soon appointed secretary of the Petrograd Soviet’s Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC). In the “operational troika” with N. I. Podvoisky and G. Chudnovsky, he coordinated the seizure of strategic points and personally led the storming of the Winter Palace on October 25/November 7, 1917, arresting the Provisional Government’s ministers—a tableau later mythologized in Soviet iconography. Trotsky himself praised him as personally courageous and capable of initiative, if politically “shaky.”

Civil War Commander in Ukraine and the South

In December 1917 Antonov-Ovseenko was appointed to command Bolshevik forces in Ukraine and southern Russia. His units helped establish Soviet power in Kharkiv and combated Cossack forces under Ataman Kaledin as well as Ukrainian nationalist and socialist formations. He opposed Brest-Litovsk and was briefly removed in 1918 for encouraging guerrilla resistance to German occupation, but soon returned as People’s Commissar for Military Affairs in Ukraine. By war’s end, he also played a prominent role in suppressing the Tambov peasant uprising (1920–21) alongside M. N. Tukhachevsky—an episode associated with extreme methods, including the use of chemical agents against insurgents.

Antonov-Ovseenko recorded these years in his multi-volume Zapiski o grazhdanskoi voine (Notes on the Civil War, 1924–33), still valued by historians for operational detail and candid political observations from a senior Bolshevik field commander.

From Oppositionist to Diplomat and Prosecutor

After the war he headed the Political Directorate of the Red Army (1922), publicly attacked the New Economic Policy, and aligned with Trotsky in the intra-party struggles—signing the “Declaration of 46” (1923). Dismissed by the Orgburo in early 1924, he was shifted into foreign service: missions to China (1923), then envoy posts to Czechoslovakia (mid-1920s), Lithuania (from 1928), and Poland (from 1930).

In 1934 he was recalled and made Prosecutor General of the RSFSR (1934–36), participating in the first Moscow show trial (Zinoviev–Kamenev) and publicly endorsing executions—an irony not lost on later commentators given his own fate. He subsequently served briefly as People’s Commissar for Justice (September–October 1937).

Barcelona, 1936–37: Consul and Enforcer

Between those judicial appointments, Moscow sent Antonov-Ovseenko to Barcelona as Consul General during the Spanish Civil War, where he became a pivotal broker of Soviet aid and a political enforcer urging the Republican government to marginalize anti-Stalinist left currents such as the POUM. His own diaries from October 1936—preserved in archival excerpts and analyzed by scholars—offer an unusually intimate diplomatic window onto Soviet policy and the fractious Republican camp during the “May Days” and after.

Arrest, Execution, and Posthumous Rehabilitation

Recalled amid the purges, Antonov-Ovseenko was arrested on the night of 11–12 October 1937, accused of belonging to a “Trotskyist terrorist and espionage organization,” and shot on February 10, 1938; his wife was executed two days earlier. He was posthumously rehabilitated on February 25, 1956, the first former Trotskyist publicly restored after Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech,” an act later defended by his son, the historian Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko.

Assessment

Antonov-Ovseenko’s political personality—impulsive, operationally gifted, and inclined to the militant left—made him indispensable in moments of insurrection and war but vulnerable in times of bureaucratic consolidation. As an executor of revolutionary violence (not least in Tambov) and later as a prosecutor endorsing lethal repression, he was both agent and victim of the Bolshevik state’s coercive turn. His Notes on the Civil War remain an essential primary source on the southern fronts, while his Barcelona diaries deepen our understanding of Soviet diplomacy within the Spanish Republic’s internecine conflicts. The trajectory from Winter Palace to Kommunarka encapsulates the paradox of the revolutionary generation: creators of a new order consumed by its terrors.

Selected Bibliography

Primary and Contemporary Sources

• Antonov-Ovseenko, Vladimir. Zapiski o grazhdanskoi voine [Notes on the Civil War]. 4 vols. Moscow: Vysshii Voen. Red. Sovet, 1924–33. (reprint: 1976).

• Antonov-Ovseenko, Vladimir. Diaries and reports from Barcelona (October 1936), archival excerpts: Russian Presidential Library, “Letter with excerpts from the diary of Consul General of the USSR in Barcelona V. Antonov-Ovseyenko…” (30 Sept–4 Oct 1936).

• Reed, John. Ten Days That Shook the World. New York: 1919. (Eyewitness characterizations of Antonov-Ovseenko’s role in Petrograd.)

• Trotsky, Leon. History of the Russian Revolution, vol. 2. London: Sphere, 1967. (Assessments of Antonov-Ovseenko’s actions in October.)

Secondary Literature

• Kowalsky, Daniel. Stalin and the Spanish Civil War (Gutenberg-e, Columbia University Press). (On Antonov-Ovseenko’s Barcelona tenure and Soviet policy.)

• Farràs, Joan Pedro. “An intimate diplomatic view: The Spanish Civil War according to the personal diaries of the Soviet Consul Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko,” International Journal of Iberian Studies 29, no. 1 (2016): 21–39.

• Conquest, Robert. The Great Terror. London: 1968; rev. eds. (Context on the 1937–38 purges and Antonov-Ovseenko’s execution).

• Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Civil War. New York: Pegasus, 2007. (Campaigns in Ukraine and the south; Tambov).

• Figes, Orlando. A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. London: Jonathan Cape, 1996. (Background on October and the Civil War).

• Antonov-Ovseyenko, Anton. The Time of Stalin: Portrait of a Tyranny. New York: Harper & Row, 1981. (Memoir-history by his son; includes rehabilitation politics).

Leave a comment