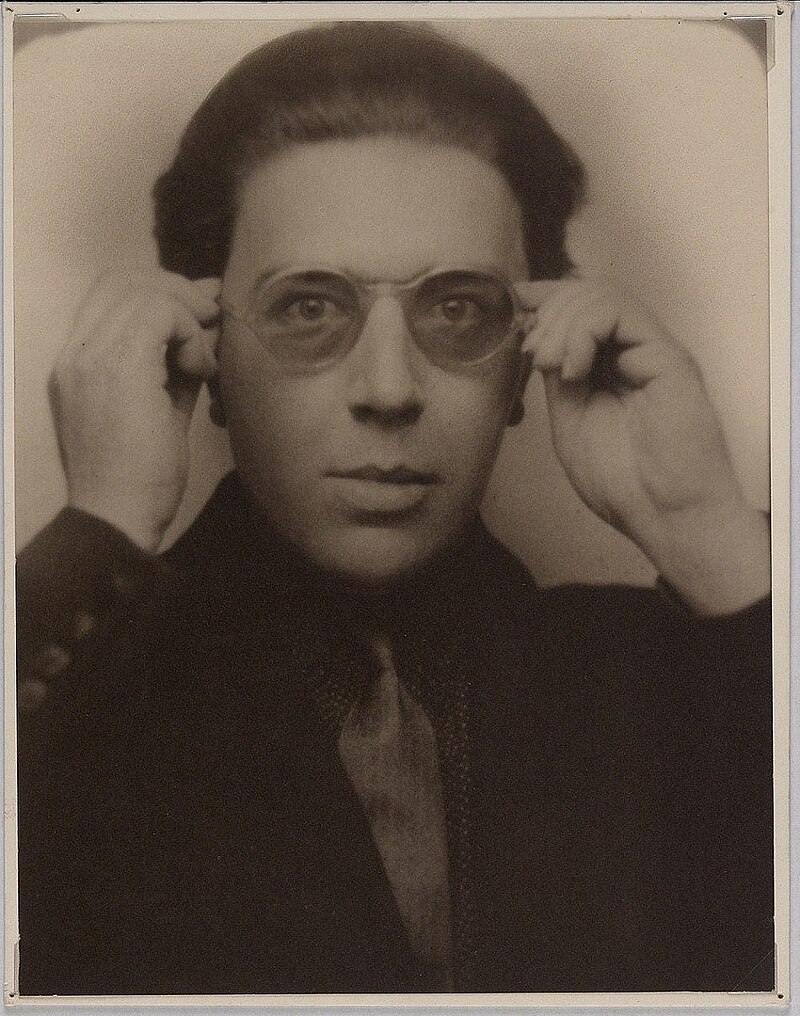

My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

André Breton (1896–1966) was born in Tinchebray, Normandy, into a modest, middle-class family. His early interest in literature was shaped by Symbolist and Decadent writers, most notably Stéphane Mallarmé and Charles Baudelaire. Initially drawn to medical studies, Breton trained in psychiatry and neurology during World War I, serving as a medical auxiliary. His exposure to shell-shocked soldiers and psychiatric patients at military hospitals in Nantes and Saint-Dizier proved formative, leading to his lifelong fascination with the unconscious, automatism, and dream states.

During this period, Breton encountered the works of Sigmund Freud, which profoundly influenced his understanding of the psyche. Freud’s ideas on dreams, repression, and the unconscious provided a theoretical framework that Breton would later fuse with radical avant-garde aesthetics.

Dada and the Birth of Surrealism

Breton’s first literary activities were intertwined with the Dada movement, which emerged in Zurich and spread to Paris in the late 1910s. He collaborated with Tristan Tzara, Louis Aragon, and Philippe Soupault, participating in Dada performances and provocations. However, Breton’s intellectual seriousness and political inclinations soon set him apart from Dada’s nihilistic anti-art stance.

In 1919, Breton and Soupault published Les Champs magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields), the first work of “automatic writing,” which attempted to transcribe thought without rational control. This experiment laid the groundwork for Breton’s leadership in the founding of Surrealism, a movement he defined in his Manifeste du surréalisme (1924) as “pure psychic automatism,” seeking to reconcile dream and reality into a superior form of truth.

Surrealism: Theory and Leadership

As the self-proclaimed “pope of Surrealism,” Breton was both its guiding force and its most dogmatic figure. He edited the influential journal La Révolution surréaliste and gathered a circle of artists and writers including Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte, and Paul Éluard. Breton envisioned Surrealism not merely as an artistic style but as a revolutionary force that could liberate human consciousness from repression.

His theoretical writings, particularly the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1930), reveal both the strength and fragility of this vision. Breton demanded loyalty to the movement’s principles, often expelling members for ideological deviations, yet his uncompromising stance also preserved the coherence of Surrealism as a radical project.

Politics and Marxism

Breton’s relationship with Marxism and revolutionary politics was complex. In the 1920s and 1930s, he attempted to align Surrealism with the revolutionary left, forging alliances with the French Communist Party (PCF). He admired Marx, Lenin, and particularly Trotsky, whose insistence on permanent revolution resonated with Surrealism’s demand for total liberation.

His 1938 Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art, co-signed with Leon Trotsky (though published under Diego Rivera’s name for political reasons), remains a landmark document. It insisted that revolutionary art must be free from both bourgeois commodification and Stalinist bureaucracy. This intervention cemented Breton’s position as an intellectual who sought to bridge avant-garde experimentation with emancipatory politics.

Nonetheless, Breton’s politics were uneven. He was expelled from the PCF for “idealism” and later clashed with figures who accused him of authoritarianism within Surrealism. Yet, from a Marxist perspective, Breton’s importance lies in his attempt to connect artistic liberation with social revolution, resisting both aesthetic formalism and Stalinist dogma.

Later Years and Legacy

Breton spent World War II in exile in the United States and the Caribbean, where he interacted with American artists and continued to champion Surrealism as a global movement. He maintained an interest in esotericism, myth, and non-Western art, broadening Surrealism’s horizons while also exposing its tensions between materialist and mystical tendencies.

Returning to France in 1946, Breton continued to write, organize exhibitions, and defend Surrealism against rival artistic movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Existentialism. His later writings emphasized ecology, myth, and the transformative power of imagination.

Breton died in Paris in 1966, leaving behind a movement that, though fractured, had permanently altered 20th-century art and literature. Surrealism’s fusion of Freudian psychoanalysis, Marxist critique, and avant-garde experimentation remains one of the most significant attempts to integrate artistic and political emancipation.

Conclusion

André Breton was not merely a poet or cultural leader but an intellectual who sought to transform consciousness and society alike. His commitment to Surrealism as both an aesthetic and revolutionary project marks him as one of the central figures of 20th-century cultural history. From a Marxist perspective, his life’s work illustrates both the promise and the contradictions of avant-garde movements: their potential to shatter bourgeois ideology, but also their susceptibility to fragmentation and idealism.

Breton’s legacy is thus dual: the visionary founder of Surrealism and the often-contradictory revolutionary who strove to reconcile art, politics, and desire into a single emancipatory project.

Bibliography

• Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969.

• Breton, André. Nadja. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Grove Press, 1960.

• Breton, André. Mad Love. Translated by Mary Ann Caws. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987.

• Caws, Mary Ann, ed. Surrealism and the Literary Imagination: A Study of Breton and Bachelard. The Hague: Mouton, 1966.

• Polizzotti, Mark. Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995.

• Rosemont, Franklin, ed. What Is Surrealism? Selected Writings of André Breton. New York: Pathfinder, 1978.

• Alexandrian, Sarane. Surrealist Art. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1970.

• Balakian, Anna. Surrealism: The Road to the Absolute. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Leave a comment