My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

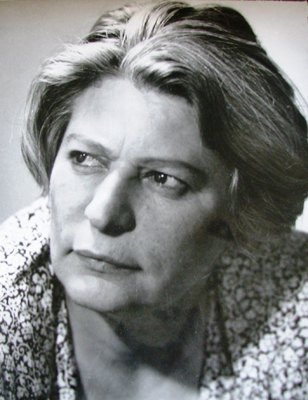

Ana Pauker—born Hana (Ana) Rabinsohn on 13 December 1893 in Codăești, Vaslui County—was the most visible face of Romanian communism in the first postwar years and, for a time, arguably the most prominent woman in the international communist movement. Her career illuminates the entanglement of ideology, empire, and national politics in East-Central Europe’s Stalinization, as well as the precarious position of Jewish communists in the late Stalin era.

Early life, political formation, and Comintern years

Raised in a poor Jewish family—her father a traditional religious scholar—Pauker trained as a teacher and was drawn into the socialist circles that flourished among radicalizing students, workers, and minority communities in the last decades of the Romanian kingdom. She affiliated with the socialist movement during World War I and, after the Bolshevik Revolution, helped found the (illegal) Romanian Communist Party (Partidul Comunist din România, PCR) in 1921.

In 1921 she married the engineer-activist Marcel Pauker, a technically trained communist whose cosmopolitan credentials and Comintern ties foreshadowed both opportunity and doom. The couple’s political work took them across interwar Europe—Vienna, Paris, Geneva, and Moscow—where Ana became a reliable Comintern cadre, able organizer, and skilled negotiator. Arrested more than once in Romania for illegal communist activity, she gained a reputation for personal austerity and party discipline.

The Great Purges in the USSR marked a private catastrophe. Marcel Pauker, recalled to Moscow, was arrested and executed in 1938. Ana, who was then working under Comintern auspices, neither publicly broke with Stalin nor voiced dissent, an accommodation that would later anchor both her authority and her vulnerability. Arrested again in Romania in 1935 and sentenced to long imprisonment, she was released in 1941 in a prisoner exchange following the Soviet annexations in 1940 and spent the war in the USSR. There she served among the Romanian émigré leadership (the so-called “Muscovite” faction), broadcasting propaganda, training cadres, and preparing for a postwar seizure of power.

Return to Romania and ascent to power

Pauker returned to Romania in late 1944 alongside the Red Army and the Soviet political apparatus. Between 1945 and 1948 she emerged—together with Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Vasile Luca, and Teohari Georgescu—as one of the pivotal actors in the forced transformation of Romania’s political order. She played key roles in the capture of the state: the subordination of the monarchy (culminating in King Michael’s abdication, 30 December 1947), the reorganization of ministries, the neutralization of rival parties, and the consolidation of a security apparatus geared toward class-war repression.

Internationally, Pauker served as Romania’s foreign minister from December 1947 to July 1952—often described as the world’s first woman to hold such a portfolio in modern times. In that capacity she executed Stalinist foreign policy: binding Romania to the emerging Soviet-led bloc, participating in the institutional architecture of the Cold War (including early COMECON coordination), and managing relations with neighboring “people’s democracies.” In the Western press—famously on the cover of Time in 1948—she was depicted as “the most powerful woman in the world,” a label that mixed fascination with Cold War orientalism and gendered sensationalism. Domestically, her authority was always contingent, embedded in factional rivalries (Muscovites vs. “prison communists” who had endured Antonescu’s jails) and ultimately dependent on Stalin’s favor.

Policies, contradictions, and the Jewish question

As a senior party leader, Pauker endorsed the core Stalinist program: land reform evolving toward collectivization, rapid nationalization of industry, political purges, strict censorship, and the suppression of real or imagined “class enemies.” Yet her tenure also contained notable inflections. She was associated with a comparatively pragmatic economic stance in 1948–50 debates (prioritizing recovery and trade channels that sometimes cut against dogmatic autarky) and, most consequentially, with a permissive policy on Jewish emigration to the new State of Israel. Between 1948 and 1951, Romania allowed a large number of Jews to emigrate—an exception in the region. Pauker’s role in facilitating this (amid negotiations that also brought hard currency and goods into Romania) became central to later accusations that she harbored “Zionist” sympathies.

These accusations intersected with the late-Stalinist campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans,” which in practice mobilized anti-Semitic tropes to police the party and the intelligentsia. In Romania, as elsewhere in the bloc, the anti-cosmopolitan turn became a weapon in factional struggles. Gheorghiu-Dej and his allies leveraged it to weaken the Muscovites and, by 1952, to eliminate Pauker from power.

Purge, eclipse, and death

In June–July 1952, Pauker was removed as foreign minister and from the party’s top leadership, along with Vasile Luca and Teohari Georgescu. She was arrested and interrogated but never publicly tried—an ambivalence reflecting both shifting signals from Moscow and intra-party calculations in Bucharest. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the climate changed; Pauker avoided a show trial but remained under surveillance and political quarantine. She died of cancer in Bucharest on 3 June 1960. Under Nicolae Ceaușescu’s bid to distance himself from Gheorghiu-Dej’s legacy, aspects of the 1952 purge were reinterpreted, and some victims were partially rehabilitated in 1968, but Pauker’s image remained contested: for official historiography, a symbol of “Muscovite” subservience; for émigré and later scholarly literature, a case study in Stalinism’s gendered and ethnic politics.

Assessment and historiographical debates

Three themes dominate the scholarly reassessment of Pauker:

1. Agency within dependency. Pauker possessed real political skill, broad networks, and tactical flexibility; yet her authority was inseparable from Soviet power. Romania’s Stalinization was not a simple imposition from Moscow nor a purely indigenous project: it was a negotiated domination in which figures like Pauker mediated, translated, and enforced a shared ideological program with local inflections.

2. Gender and representation. Pauker’s prominence destabilizes assumptions about the masculine monopoly of high politics in early Cold War Eastern Europe. At the same time, the spectacularization of her image—in Western media and domestic propaganda alike—was infused with gendered stereotypes (the iron-fisted “Red Pasionaria”) that alternately demonized and instrumentalized her.

3. Jewishness, anti-cosmopolitanism, and the politics of loyalty. A Jewish communist at the apex of a Stalinist party, Pauker embodied the paradox of inclusion and exclusion: elevated by a universalist ideology that claimed to transcend ethnicity, then targeted by a state campaign deploying ethno-nationalist suspicion. Her support for Jewish emigration—interpreted by some as humanitarian pragmatism and by others as factional or “Zionist” deviation—proved politically ruinous in the climate of 1952.

Today, Pauker stands as a prism through which to analyze the logics of Stalinist rule: its promise of revolutionary transformation, its reliance on coercive modernization, its suspicion of plural identities, and its cyclical purging of loyal servants. The best scholarship neither rehabilitates nor demonizes her; it situates her choices within a system that rewarded ruthlessness, punished nuance, and ultimately consumed many of its architects.

Bibliography

• Deletant, Dennis. Romania under Communist Rule. Bucharest: Civic Academy Foundation, 1997.

• Hitchins, Keith. Romania 1866–1947. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

• Iordachi, Constantin, and Dorin Dobrincu, eds. Transforming Peasants, Property and Power: The Collectivization of Agriculture in Romania, 1949–1962. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2009.

• Levy, Robert. Ana Pauker: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Communist. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

• Levy, Robert. “Ana Pauker and the Cold War in Romania.” Cold War History 2, no. 3 (2002): 1–26.

• Tismăneanu, Vladimir. Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

• Verdery, Katherine. National Ideology under Socialism: Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceaușescu’s Romania. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. (For broader interpretive context.)

• Vescovi, Maria Bucur (Bucur, Maria). Heroes and Victims: Remembering War in Twentieth-Century Romania. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009. (Memory politics context.)

• Zahariade, Ana-Maria, ed. The Red Mouth of the Dragon: Romanian Communism and Its Legacies. Bucharest: New Europe College, 2010. (Essays on structures and legacies.)

• Time. “Romania: Red Queen in the Balkans.” Cover story on Ana Pauker. 20 September 1948. (Contemporary Western representation.)

Leave a comment