My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

Introduction

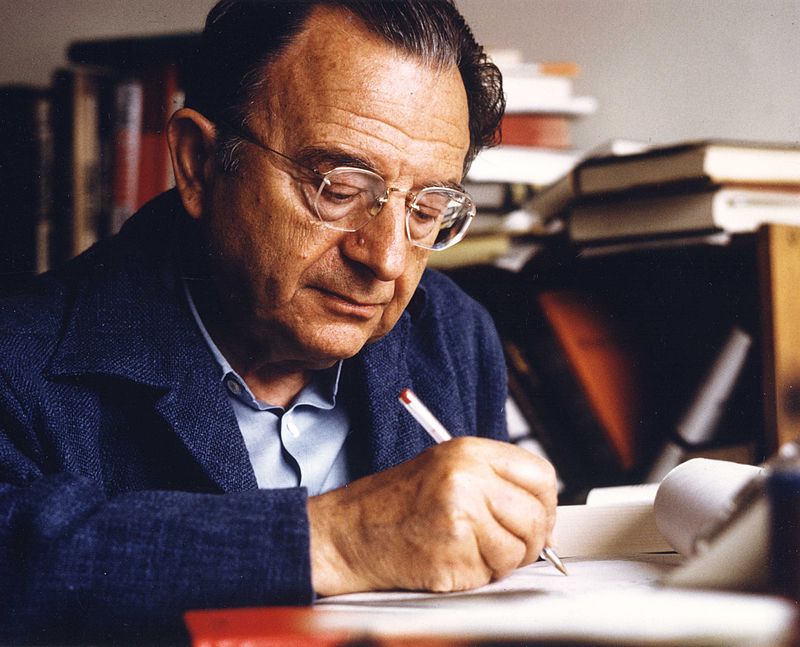

Erich Fromm (1900–1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, humanist philosopher, and Marxist thinker whose interdisciplinary synthesis of psychology, sociology, and critical theory profoundly shaped 20th-century social thought. A member of the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory, Fromm bridged the gap between Freudian psychoanalysis and Marxist social critique, arguing that the crisis of modern civilization lay in the alienation of the individual within capitalist society. His central project was the recovery of human freedom through an ethics of love, creativity, and social solidarity—what he called “humanistic socialism.”

Early Life and Education

Born on March 23, 1900, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Erich Fromm was the only child of Orthodox Jewish parents, Naphtali and Rosa Fromm. His upbringing in a devout household instilled a deep engagement with moral and existential questions that would later inform his intellectual humanism. After completing secondary school, Fromm studied sociology at the University of Frankfurt under Alfred Weber and Karl Mannheim, and received his Ph.D. from the University of Heidelberg in 1922 with a dissertation on Jewish law (Das jüdische Gesetz: Ein Beitrag zur Soziologie des Diaspora-Judentums).

His intellectual formation occurred amid the ferment of the Weimar Republic, where psychoanalysis, Marxism, and sociology converged as tools to interpret modernity’s discontents. Fromm trained as a psychoanalyst at the Berlin Institute for Psychoanalysis between 1924 and 1930 under Hanns Sachs and Theodor Reik, affiliating himself with the left wing of psychoanalytic thought.

The Frankfurt School and Exile

Fromm’s collaboration with the Institute for Social Research (founded in 1923 and later known as the Frankfurt School) began in 1929. There, he developed a socio-psychological dimension to Marxist theory, proposing that economic structures not only condition social relations but also produce distinct psychological types—the “authoritarian character” and the “marketing character,” for example. His 1932 essay The Method and Function of an Analytic Social Psychology outlined a synthesis of Freud and Marx, suggesting that the contradictions of capitalist society were internalized within the individual psyche.

The rise of Nazism forced Fromm, who was of Jewish descent, to flee Germany in 1934. He settled first in Geneva and then in New York, where he joined the faculty of Columbia University and helped to establish a psychoanalytic practice. His intellectual break with orthodox Freudianism became increasingly evident during this period: unlike Freud, Fromm rejected instinctual determinism and the death drive, emphasizing instead the social origins of psychic pathology and the potential for human self-realization within a rational, cooperative society.

Major Works and Intellectual Development

Fromm’s prolific writings during the mid-20th century reflect his attempt to articulate a comprehensive critique of capitalist modernity and a vision for human liberation.

• Escape from Freedom (1941) — perhaps his most famous work—analyzes the psychological conditions that make modern individuals susceptible to authoritarianism. Written during the ascent of fascism, it argues that capitalism’s atomization of the individual creates unbearable anxiety, prompting a retreat into submission or conformity.

• Man for Himself (1947) expands on his humanistic ethics, advocating for a morality grounded in productive love and self-realization rather than obedience to external authority.

• The Sane Society (1955) represents a critique of postwar consumer capitalism, where individuals become commodities within a “marketing orientation.”

• The Art of Loving (1956), his most widely read book, distills his philosophical humanism into an accessible exploration of love as a discipline and practice—a form of active, creative care for others and oneself.

• Marx’s Concept of Man (1961) and Beyond the Chains of Illusion (1962) reaffirm Fromm’s lifelong commitment to the humanist essence of Marx’s early writings, countering both Stalinism and mechanistic interpretations of Marxism.

• Later works such as The Revolution of Hope (1968) and To Have or to Be? (1976) continue this humanistic socialism, opposing the acquisitive “having” mode of existence to the creative “being” mode, a distinction deeply resonant with ecological and existential thought.

Philosophical and Theoretical Contributions

Fromm’s theoretical synthesis can be understood as a dialectical project uniting Marxian social theory and Freudian depth psychology. While his contemporaries in the Frankfurt School (notably Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse) often viewed him as overly idealistic, Fromm insisted that genuine social transformation must be accompanied by psychic transformation. Alienation, he argued, is not merely an economic condition but an existential one: capitalism estranges individuals from their own human potential, transforming living persons into things.

Fromm’s humanistic psychoanalysis emphasized the capacity for love, reason, and creative work as the essence of human nature. He defined freedom not simply as the absence of constraint but as the positive ability to realize one’s humanity in community with others. In this respect, he departed from both Freudian pessimism and Marxist determinism, articulating a humanism of praxis grounded in ethical socialism.

His concept of the “social character”—a patterned matrix of psychological traits shared by members of a society—remains one of his enduring contributions to critical social psychology, anticipating later developments in political psychology and cultural studies.

Later Life and Legacy

Fromm emigrated to Mexico in 1950, where he joined the faculty of the National Autonomous University of Mexico and founded the Mexican Institute of Psychoanalysis. He later maintained affiliations with Michigan State University and New York University. His writings from this period reflected both his growing ecological concern and his disillusionment with Cold War capitalism and bureaucratic socialism alike.

Fromm spent his final years in Muralto, Switzerland, where he continued to write until his death in 1980. His thought remains influential across multiple disciplines—psychology, sociology, theology, philosophy, and political theory.

Fromm’s fusion of Marxist humanism and existential psychoanalysis inspired figures from Paulo Freire to liberation theologians, and his insistence that “the full development of man is the end of all social arrangements” situates him firmly within the emancipatory tradition of critical thought.

Conclusion

Erich Fromm’s intellectual legacy lies in his profound defense of human dignity against the twin threats of authoritarianism and commodification. His critique of alienated modernity anticipated the psychological malaise of neoliberalism, while his vision of a “sane society” remains a challenge to both capitalist and bureaucratic rationality. By linking the inner world of desire to the outer world of social relations, Fromm offered a dialectical humanism grounded in both love and revolution—a synthesis as ethically compelling as it is politically urgent.

Selected Bibliography

Primary Works

• Fromm, Erich. Escape from Freedom. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1941.

• ———. Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics. New York: Rinehart, 1947.

• ———. The Sane Society. New York: Rinehart, 1955.

• ———. The Art of Loving. New York: Harper & Row, 1956.

• ———. Marx’s Concept of Man. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1961.

• ———. Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx and Freud. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.

• ———. The Revolution of Hope: Toward a Humanized Technology. New York: Harper & Row, 1968.

• ———. To Have or to Be? New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Secondary Sources

• Burston, Daniel. The Legacy of Erich Fromm. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

• Funk, Rainer. Erich Fromm: His Life and Ideas—An Illustrated Biography. New York: Continuum, 2000.

• McLaughlin, Neil. Erich Fromm and the Critical Imagination: Beyond the Authoritarian Personality. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999.

• Thompson, Michael. The Politics of Truth: From Marx to Foucault. New York: Peter Lang, 2004.

• Bronner, Stephen Eric. Critical Theory and Its Theorists. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Leave a comment