Book Review

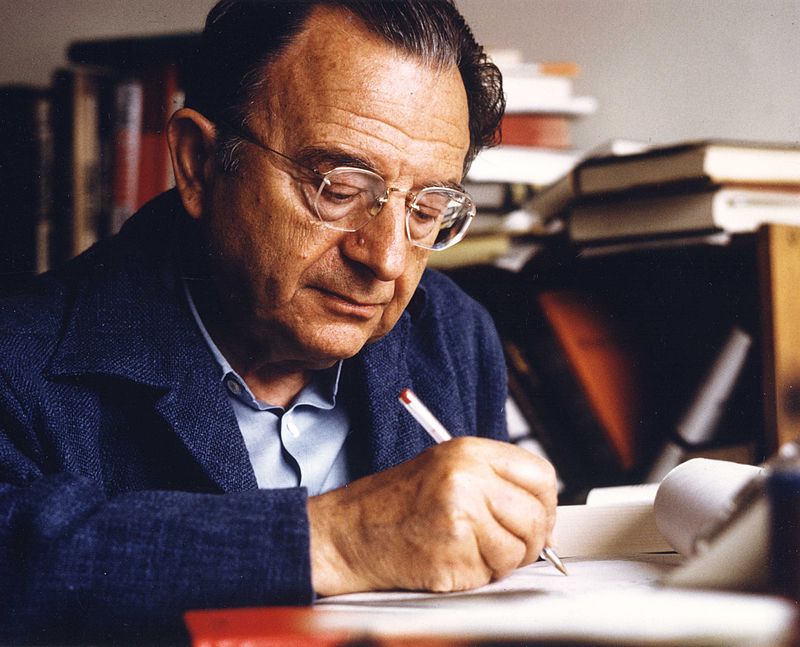

Fromm, Erich. Escape from Freedom. Holt Paperbacks, 1994.

Erich Fromm’s Escape from Freedom (originally The Fear of Freedom, 1941; Holt, 1994 reprint) stands as one of the most penetrating psychoanalytic examinations of modern bourgeois society through a dialectical lens. Though not a Marxist in the orthodox sense, Fromm’s analysis of individual autonomy under capitalism converges profoundly with revolutionary Marxist critique. His fusion of Marx and Freud anticipates the later Frankfurt School’s efforts to integrate the economic and the psychological dimensions of domination.

Freedom, Alienation, and the Bourgeois Self

Fromm’s central thesis—that modern “freedom from” traditional authority masks a deeper “freedom to” conform to the demands of capital—resonates with Marx’s early writings on alienation. The bourgeois subject, ostensibly emancipated from feudal constraints, finds himself ensnared in new forms of dependence: wage labor, market competition, and ideological interpellation. Fromm’s notion of “escape” through authoritarianism, destructiveness, or automaton conformity parallels Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism: both identify how freedom under capitalism becomes distorted into submission to impersonal forces.

Fromm situates fascism as a pathological reaction to the anxiety produced by capitalist individuation. This insight carries revolutionary weight: the fascist psyche, in his account, is not an anomaly but the logical outgrowth of a social order that replaces solidarity with competition. His psychological diagnosis complements Marx’s structural one—together they expose how the capitalist mode of production engenders the very authoritarian personalities that sustain it.

The Dialectic of Freedom and Necessity

Fromm’s analysis implicitly develops the dialectical relation between freedom and necessity that Marx treats in Capital. The “freedom” of the modern subject is abstract, formal, and emptied of material content; it conceals the necessity imposed by class domination. True freedom, in a Marxist sense, emerges only through the collective transformation of social relations—the abolition of private property and the end of alienated labor. Fromm’s call for “positive freedom,” rooted in spontaneous activity and productive love, thus gestures toward the humanist core of Marx’s communism: the liberation of creative powers from the fetters of capital.

While Fromm couches his vision in existential and humanist terms rather than in the language of class struggle, his critique of capitalist personality formation opens a pathway toward revolutionary praxis. The psychological mechanisms he exposes—fear of isolation, compulsive conformity, the worship of authority—remain the interior armature of ideological control. A revolutionary Marxist reading of Escape from Freedom thus interprets Fromm’s “escape” not merely as a psychological event but as a social process to be overcome through collective emancipation.

Fromm’s Legacy in Revolutionary Thought

Fromm’s synthesis of psychoanalysis and Marxism anticipates the critical theory of Herbert Marcuse, whose Eros and Civilization extends Fromm’s insight into the libidinal economy of repression. For revolutionary Marxists, Escape from Freedom endures as an indispensable text for understanding how capitalism reproduces itself through subjectivity. Its enduring relevance lies in revealing that the struggle for socialism must be fought not only in the realm of production but within the psyche itself.

Far from being a liberal plea for tolerance, Fromm’s book, when read dialectically, becomes a radical indictment of bourgeois “freedom.” It exposes how individualism under capitalism functions as a mechanism of control and how only a revolutionary transformation of society can reconcile individuality and solidarity.

Conclusion

In sum, Escape from Freedom is not simply a work of social psychology—it is a prefiguration of revolutionary humanism. Fromm’s insistence that true freedom demands active, conscious participation in shaping history aligns profoundly with Marx’s dictum that “the philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point, however, is to change it.”

Leave a comment