My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

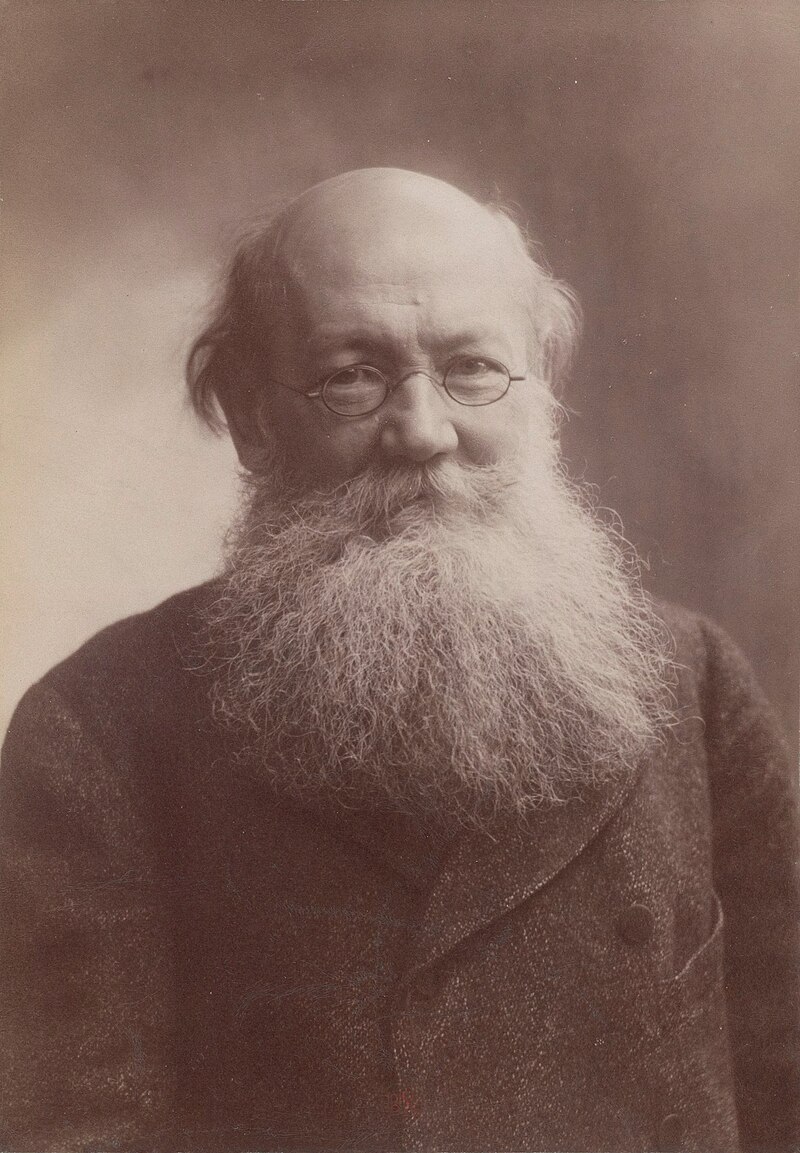

Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (1842–1921) stands as one of the foremost revolutionary thinkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—a scientist, geographer, and anarchist communist whose life and writings synthesized Enlightenment rationalism, Darwinian science, and socialist ethics into a coherent theory of mutual aid and decentralized social cooperation. His intellectual trajectory, shaped by both aristocratic privilege and revolutionary conscience, embodies the dialectic between scientific materialism and moral insurgency that animated the broader socialist movement of his time.

Early Life and Education

Born into the Russian nobility in Moscow, Kropotkin was the son of Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, a general in the imperial army, and Yekaterina Nikolaevna Sulima. His early education at the Corps of Pages in St. Petersburg—an institution reserved for the sons of the elite—placed him in proximity to Tsar Alexander II’s court, where he first developed a critical awareness of autocracy and social inequality. Rejecting the privileges of his class, Kropotkin volunteered for service in Siberia in 1862, an experience that would profoundly shape his worldview.

In Siberia, as an officer and later as a geographer attached to the Russian Geographical Society, Kropotkin conducted expeditions that yielded significant contributions to physical geography and glaciology, particularly his studies of the orography of Eastern Siberia and the glacial formation of the Eurasian plains. Yet the stark poverty of the peasants and the cruelty of the penal colonies transformed him into a revolutionary. By 1872, after reading the works of Proudhon and encountering the International Workingmen’s Association in Switzerland, he declared himself an anarchist.

Revolutionary Activity and Imprisonment

Kropotkin’s return to Russia marked the beginning of his political militancy. He joined the radical “Circle of Tchaikovsky,” an organization that propagated socialist ideas among workers and peasants. Arrested in 1874, he was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress. His escape in 1876, through a daring plan involving friends and a waiting carriage, became legendary among Russian revolutionaries. Fleeing to Western Europe, he settled in Switzerland and later in France, where he became a central figure in the development of anarchist communism.

His years in exile were marked by continuous activism: he co-founded the Le Révolté newspaper (later La Révolte and Les Temps Nouveaux) and participated in international anarchist congresses. Arrested again in 1882 in France during the wave of repression following the Lyon trial, he served three years in the Clairvaux prison, during which he wrote extensively on political economy and evolutionary ethics.

Theoretical Contributions

Kropotkin’s theoretical corpus redefined anarchism in scientific and ethical terms. In works such as Words of a Rebel (1885), The Conquest of Bread (1892), and Fields, Factories, and Workshops (1899), he elaborated a vision of a decentralized, cooperative society rooted in communal ownership and voluntary association. Rejecting both state socialism and laissez-faire capitalism, Kropotkin argued that the state itself was an instrument of class domination and that genuine social order could only arise from the free federation of communes and labor associations.

His scientific background informed his political philosophy. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902) stands as his most enduring contribution, challenging the Social Darwinist emphasis on competition. Drawing from extensive zoological and ethnographic evidence, Kropotkin argued that cooperation and solidarity were key evolutionary mechanisms, both biologically and socially. This work bridged evolutionary theory and socialist ethics, prefiguring later ecological and communitarian thought.

Later Life and the Russian Revolution

Kropotkin died in Dmitrov in 1921. His funeral became the last public demonstration of anarchist sentiment in Soviet Russia, attended by tens of thousands who carried black flags emblazoned with “Where there is authority, there is no freedom.”

Legacy and Influence

Kropotkin’s influence extends far beyond the confines of anarchist theory. His synthesis of science and socialism provided a foundation for ecological and communitarian thought, influencing figures such as Lewis Mumford, Murray Bookchin, and even elements of modern environmental ethics. His critique of hierarchy and advocacy for decentralized cooperation anticipated twentieth-century discussions on participatory democracy and cooperative economics.

Within Marxist circles, Kropotkin was often dismissed for his idealism and anti-statism, yet his ethical socialism and faith in human solidarity continue to resonate as a counterpoint to authoritarian models of revolution. As a thinker, he straddled the intellectual fault lines between positivism and utopianism, materialism and moral idealism, revolution and reform.

Kropotkin remains, in the words of historian George Woodcock, “a prince who abandoned his heritage to become the prophet of a humanity freed from both state and capital.”

Bibliography

• Avrich, Paul. The Russian Anarchists. Princeton University Press, 1967.

• Cahm, Caroline. Kropotkin and the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism, 1872–1886. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

• Kropotkin, Peter. The Conquest of Bread. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906.

• ———. Fields, Factories, and Workshops. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1912.

• ———. Memoirs of a Revolutionist. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1899.

• ———. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. London: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1902.

• Miller, Martin A. Kropotkin. University of Chicago Press, 1976.

• Shatz, Marshall S. Kropotkin: The Politics of Community. Black Rose Books, 1993.

• Woodcock, George, and Ivan Avakumović. The Anarchist Prince: A Biographical Study of Peter Kropotkin. New York: Schocken Books, 1950.

Leave a comment