My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

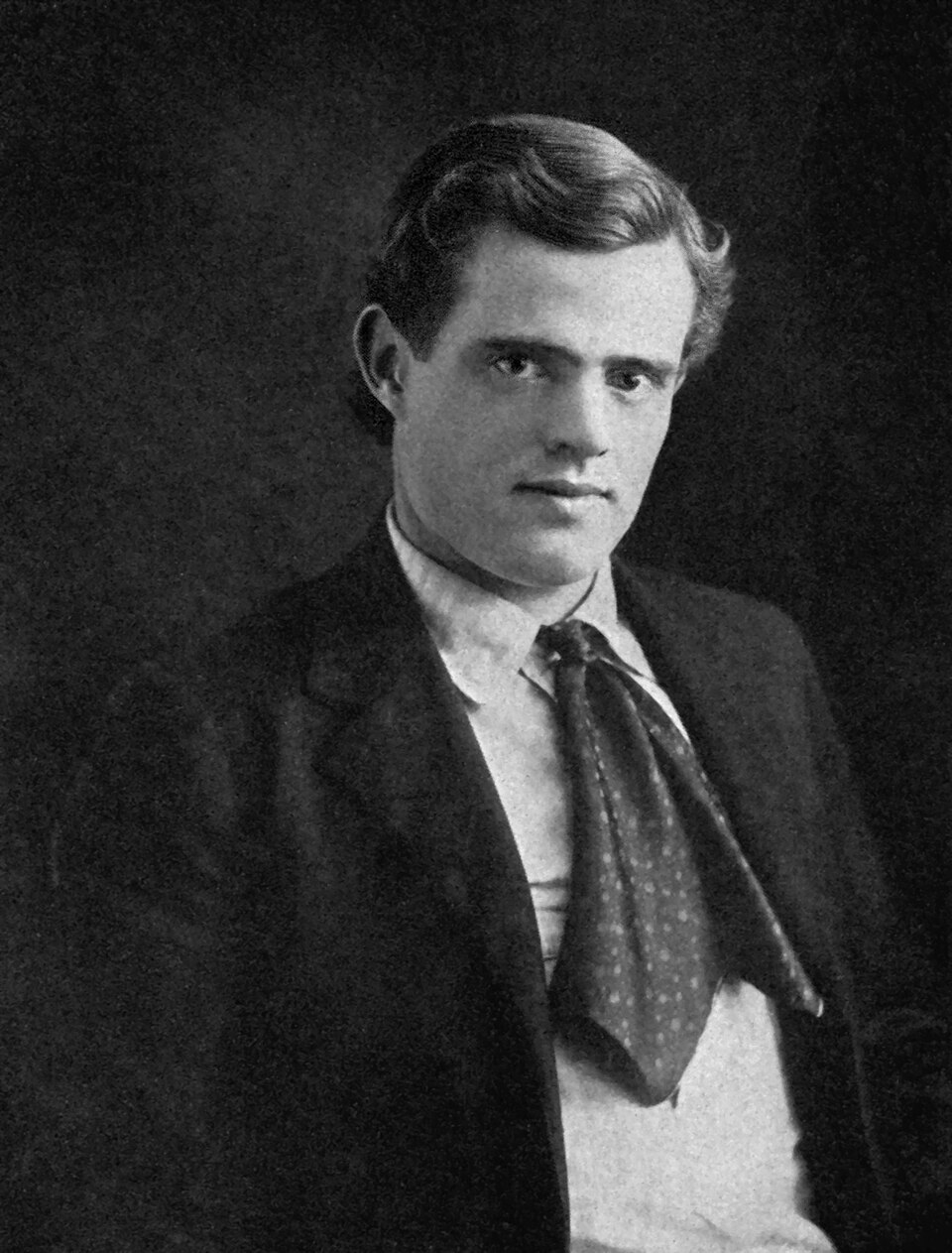

Jack London (1876–1916) remains one of the most widely read American authors of the early twentieth century, acclaimed for adventure novels such as The Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906). Yet beneath the veneer of rugged individualism and frontier adventure lies a writer deeply engaged with the contradictions of industrial capitalism, class struggle, and the socialist movement. His life and works must be understood as both products of, and interventions in, the era of rapid capitalist expansion and imperial conquest in which he lived.

Early Life and Class Experience

Born in San Francisco to a working-class family of precarious means, London’s youth was marked by economic hardship. He worked in canneries, as a sailor, and as a tramp laborer—experiences that shaped his early sense of exploitation and solidarity with the dispossessed. These years instilled in him a visceral awareness of class struggle, which he would later articulate in his political essays and socialist fiction. His autodidactic education, gained largely in public libraries and later at the University of California, Berkeley (which he attended briefly), exposed him to evolutionary theory, Marxist thought, and the radical press.

Socialist Convictions and Political Engagement

London joined the Socialist Labor Party in the 1890s and later the Socialist Party of America, becoming one of its most prominent literary figures. His speeches and articles often targeted the injustices of capitalism, and he twice ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Oakland on the Socialist ticket (1901 and 1905). His political commitments were not merely rhetorical; they reflected a broader attempt to integrate art with agitation.

In essays such as How I Became a Socialist (1903), London grounded his socialism in direct personal experience of poverty and wage labor. He frequently emphasized the dehumanizing effects of industrial capitalism, which he saw as reducing workers to “beasts of burden” while concentrating wealth in the hands of a few. His socialism was heavily inflected with a Darwinian materialism: he accepted the struggle for survival as a natural law, but insisted that collective organization and socialist transformation were the only means to humanize that struggle.

Socialist Themes in Literature

London’s fiction reflects his socialist convictions as much as his essays. The People of the Abyss (1903), a documentary account of his time living among the poor in London’s East End, exposed the brutal realities of urban poverty in the world’s leading capitalist metropolis. The Iron Heel (1908), perhaps his most overtly socialist novel, anticipates the rise of a corporate oligarchy that crushes working-class uprisings—a prescient dystopia that foreshadowed later critiques of fascism and monopoly capitalism.

Even works popularly understood as tales of individual adventure can be read through a socialist lens. The Call of the Wild dramatizes the brutality of natural selection, but also the possibility of community and collective survival. Martin Eden (1909), a semi-autobiographical novel, critiques the ideology of rugged individualism by depicting a working-class writer who pursues bourgeois success only to discover its emptiness, culminating in despair and suicide. These works reveal London’s ambivalence toward American capitalism—admiring its dynamism while condemning its exploitative core.

Contradictions and Limitations

London’s socialism was not without contradiction. His embrace of scientific materialism sometimes shaded into biological determinism, and at times he espoused views—particularly on race and eugenics—that sat uneasily with his egalitarian commitments. He admired Nietzsche as much as Marx, and his political writings oscillate between proletarian solidarity and elitist notions of the “superman.” Nevertheless, his commitment to socialism was sincere and persistent; he consistently used his platform to popularize the socialist cause and to dramatize the stakes of class struggle.

Legacy

Jack London’s legacy as a writer is inseparable from his socialist politics. While he achieved immense commercial success, he remained committed to articulating the struggles of workers and envisioning alternatives to capitalist domination. His blend of adventure narrative, scientific materialism, and socialist critique made him a unique voice in American letters. Today, his writings offer both a record of early twentieth-century socialist thought and a still-relevant indictment of capitalism’s dehumanizing tendencies.

Bibliography

• London, Jack. The Iron Heel. New York: Macmillan, 1908.

• London, Jack. The People of the Abyss. London: Isbister & Co., 1903.

• London, Jack. How I Became a Socialist. The Comrade, Vol. 2, No. 5, 1903.

• London, Jack. Martin Eden. New York: Macmillan, 1909.

• London, Jack. The Call of the Wild. New York: Macmillan, 1903.

Secondary Sources

• Foner, Philip S. Jack London: American Rebel. New York: The Citadel Press, 1947.

• Labor, Earle, ed. The Letters of Jack London. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

• Labor, Earle, and Jeanne Campbell Reesman. Jack London: A Life. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

• Walker, Franklin. Jack London and the Klondike. San Marino: Huntington Library, 1966.

• Williams, Jay. Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London, 1893–1902. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Leave a comment