My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

Introduction

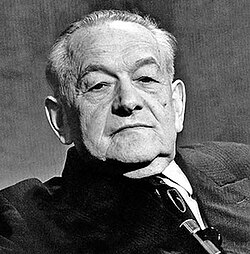

Leopold Trepper (1904–1982) stands as one of the most significant figures in the history of twentieth-century espionage, resistance movements, and Soviet intelligence operations during World War II. As the chief architect of the “Red Orchestra” (Rote Kapelle), Trepper orchestrated one of the most effective and complex anti-Nazi intelligence networks in occupied Europe. His life intersects with the history of European communism, Jewish resistance, and Cold War politics, offering a lens into the transnational networks of the revolutionary left and Soviet clandestine operations.

Early Life and Political Formation

Born on February 23, 1904, in Nowy Targ, in the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia (today Poland), Trepper came from a poor Jewish family. He grew up amid the economic hardships and ethnic tensions of post-World War I Eastern Europe, experiences that profoundly shaped his political consciousness. Drawn to Marxism and revolutionary politics in his youth, he joined the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) in the 1920s. His early political activity included organizing strikes and disseminating communist propaganda, actions that led to his first arrests and encounters with the repressive apparatuses of interwar states.

By the early 1930s, Trepper was increasingly integrated into the international communist movement, aligning himself with the Comintern and Soviet intelligence services. His linguistic skills—fluent in Polish, French, Russian, and German—and his cosmopolitan experiences made him particularly valuable as a courier and operative in transnational communist networks.

Rise within Soviet Intelligence and the Red Orchestra

In 1932, Trepper emigrated to the Soviet Union, where he formally entered the orbit of Soviet military intelligence, the GRU. The Stalinist purges of the late 1930s decimated much of the Soviet intelligence leadership, but Trepper survived this political upheaval and was soon deployed to Western Europe.

In 1938–39, he established the foundation for what became the Red Orchestra, a sprawling network of communist, anti-fascist, and sympathetic informants across Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Germany itself. Operating primarily under commercial cover—including the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company in Brussels—Trepper constructed parallel communication and intelligence-gathering infrastructures that funneled vast amounts of military, political, and economic data back to Moscow.

During the early years of World War II, the Red Orchestra provided critical intelligence on German military planning, including details on Operation Barbarossa, the planned invasion of the Soviet Union. Although Stalin notoriously dismissed many of these warnings, the network’s contributions to Soviet and Allied intelligence efforts remain historically significant.

Arrest, Imprisonment, and Postwar Complexities

In late 1942, Trepper was betrayed and captured by the Gestapo in Paris. Remarkably, he managed to manipulate his German captors, maintaining secret contacts with the French Resistance while ostensibly cooperating with Nazi intelligence. In 1943, he escaped from German custody under dramatic circumstances, hiding in France until the war’s end.

However, Trepper’s postwar fate reflected the Stalinist regime’s deep suspicion of returned operatives. Upon his return to the USSR in 1945, he was arrested by the NKVD and spent a decade in Soviet prisons and labor camps. Only after Stalin’s death in 1953 and the subsequent political thaw was Trepper rehabilitated and allowed to leave the USSR.

Later Life, Memoirs, and Legacy

In 1973, Trepper emigrated to Israel, though he maintained a complicated relationship with Zionism, communism, and the Soviet legacy. His memoir, The Great Game (Le Grand Jeu), published in 1975, remains a seminal firsthand account of Soviet espionage and anti-Nazi resistance, blending personal narrative with political history.

Leopold Trepper died on January 19, 1982, in Jerusalem. Historiographically, he occupies a liminal position: celebrated as a resistance hero, criticized for his ties to Stalinism, and studied as a central figure in the history of twentieth-century intelligence. Scholars continue to debate the full scope of his network’s contributions and the political ambiguities of his life under communism and Cold War realpolitik.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

• Trepper, Leopold. The Great Game: Memoirs of the Spy Hitler Couldn’t Silence. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977.

• Trepper, Leopold. Le Grand Jeu. Paris: Editions Robert Laffont, 1975.

Secondary Sources

• Jeffery, Keith. The Secret History of MI6: 1909–1949. New York: Penguin Press, 2010.

• Nelson, Anne. Red Orchestra: The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends Who Resisted Hitler. New York: Random House, 2009.

• West, Nigel. MI6: British Secret Intelligence Service Operations, 1909–1945. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1983.

• Dallin, David J. Soviet Espionage. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955.

• Andrew, Christopher, and Vasili Mitrokhin. The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. London: Penguin, 1999.

Leave a comment