Introduction

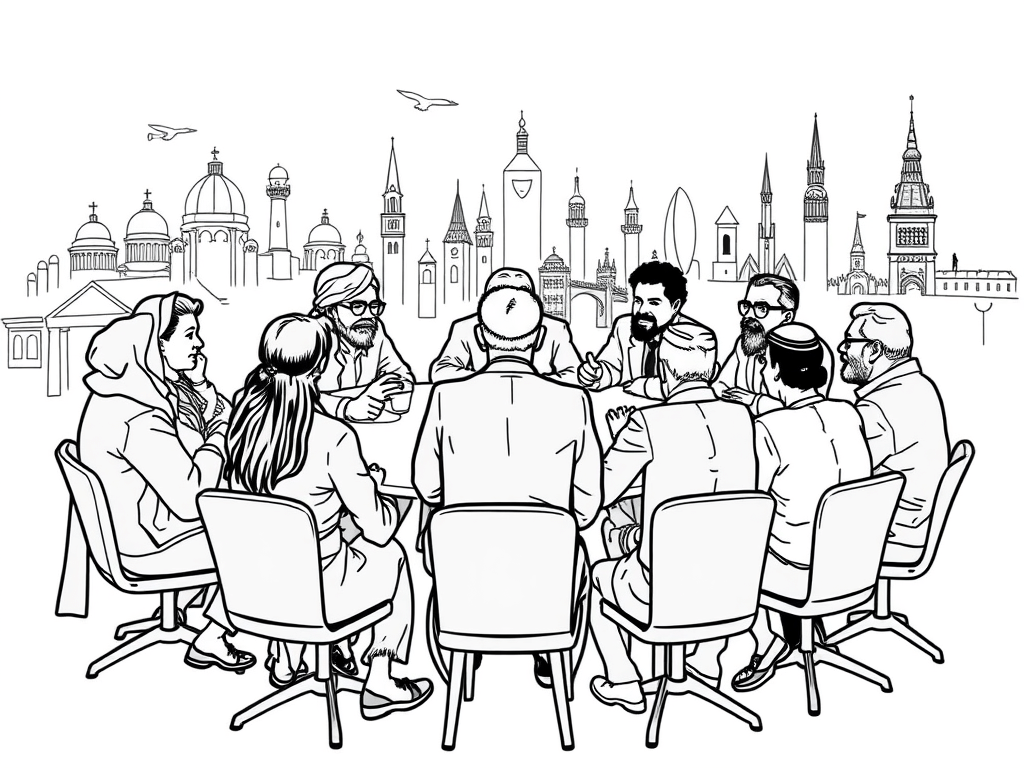

In the decade from 2015 to 2025, Marxist philosophy has experienced a notable revival and diversification worldwide. Ongoing crises of global capitalism – from financial instability to soaring inequality and climate emergency – have spurred renewed interest in Marx’s critique of society. Across Western Europe, North America, Latin America, Asia, and beyond, intellectuals have reinterpreted Marxism in dialogue with regional contexts and other critical theories. Marxist thought has both drawn on its traditional frameworks and ventured into new syntheses, intersecting with feminism, post-colonialism, critical race theory, and ecological thought. Major conferences (such as the “Marx 200” bicentenary events in 2018) and publications have marked this resurgence, bringing together veteran theorists and new voices. This essay surveys the key global trends in Marxist philosophy over the last ten years, highlighting influential figures, schools of thought, and debates that have shaped contemporary Marxist discourse. It is organized by region and theme, to illuminate both geographical developments and thematic intersections. The overall picture is one of a pluralistic Marxism evolving to address 21st-century realities while remaining grounded in core critiques of capitalism.

Western Europe: Revivals and Reinterpretations

Western Europe has long been a cradle of Marxist theory, and in the past decade it continued to produce vibrant philosophical debates. A significant trend was a “return to Marx” in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the Eurozone turmoil. Intellectuals revisited Marx’s Capital to analyze austerity and neoliberalism’s failures. In Germany, for example, the Neue Marx-Lektüre (“New Reading of Marx”) school gained traction, offering fresh interpretations of Das Kapital and Marx’s value theory. Thinkers like Michael Heinrich questioned orthodox views on value and crisis, sparking debates in Marxist journals on the labor theory of value and the falling rate of profit. These scholarly debates kept Marx’s economic philosophy alive and contentious. At the same time, Western European theorists grappled with the political legacy of Marxism in the post-Soviet era. Italian philosophers Gianni Vattimo and Santiago Zabala, in their Hermeneutic Communism (2011), proposed a “weak communism” adapted to democratic contexts, praising Latin America’s socialist experiments as a new model. This reflected a broader Western European interest in reformulating Marxist strategy for pluralistic societies.

Prominent figures such as Slavoj Žižek and Alain Badiou remained influential. Žižek, a Slovenian theorist rooted in the Western Marxist tradition, continued his blend of Marxism with Lacanian psychoanalysis, famously insisting “Why I am still a Communist” in debates and writing about the prospects of radical change on Marx’s bicentenary. Badiou, in France, upheld the “communist hypothesis,” suggesting that the idea of communism is an eternal possibility to be reinvented. Conferences like “The Idea of Communism” (held in various European cities earlier in the decade) and Historical Materialism annual gatherings in London and Athens drew large audiences, evidencing Marxism’s enduring appeal in theoretical circles. Another noteworthy current was the accelerationist debate that emerged from British academia. Left-accelerationists such as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams argued in Inventing the Future (2015) that technological acceleration under capitalism could be repurposed to hasten a post-capitalist society. While some traditional Marxists saw this as heretical, it stimulated discussion on automation, universal basic income, and the future of work. Meanwhile, European social movements – from the rise of Syriza in Greece to Spain’s Podemos and Britain’s Jeremy Corbyn phenomenon – drew intellectual support from Marxist analyses of capitalism’s contemporary contradictions. Although these left-populist movements were political, they invigorated Marxist philosophical discussions about strategy: the balance between class politics and “populist” appeals, and the relevance of Leninist party organization today. Figures like Jodi Dean (an American often engaged in European debates) advocated a return to disciplined party politics in Crowds and Party (2016), resonating with some European Marxists seeking an organizational answer to neoliberal hegemony.

Despite these innovations, Western Marxism also faced self-critique. Some argued it had become too academic and detached from praxis. As Marxist scholar Alex Callinicos quipped, Western Marxists at times resemble Narcissus, “in love with [their] own reflection,” producing highly theoretical writings “incomprehensible to all but a tiny minority.” This tension between theory and practice remains a central concern. Nonetheless, the Western European scene of 2015–2025 shows a rich tapestry: re-readings of Marx’s texts, philosophical experiments (from hermeneutic communism to accelerationism), and ongoing dialogue about how Marxist theory can guide transformative action in liberal-democratic conditions.

North America: Marxism, Intersectionality, and Renewal

In North America, Marxist philosophy over the last decade has both drawn from Europe’s theoretical contributions and developed in distinctive directions. The United States and Canada saw a modest resurgence of socialist ideas in the public sphere alongside new theoretical syntheses in the academy. A notable trend was the intersection of Marxism with analyses of race and gender, reflecting the diverse fabric of North American society. Critical race theory and Marxism found points of convergence in the concept of racial capitalism, which examines how capitalism and racism are mutually constitutive. The late historian Cedric J. Robinson’s work Black Marxism (reissued and discussed widely in the 2010s) introduced the idea that modern capitalism emerged entwined with racial hierarchies, a thesis taken up by scholars like Robin D.G. Kelley and widely cited during the Black Lives Matter era. This helped foreground a Marxist analysis of racial oppression in mainstream discourse, in contrast to older class-reductionist approaches. Debates ensued between proponents of “race-first” perspectives and classical Marxists: for instance, writers like Adolph Reed Jr. critiqued what they saw as excessive identity politics, arguing for the primacy of class in anti-capitalist strategy, whereas others insisted Marxism must account for specific histories of racialized exploitation. Such debates, often heated, have nonetheless enriched Marxist philosophy by forcing it to address the racial blind spots in its tradition. The concept of intersectionality – originating in Black feminist thought – became increasingly incorporated into Marxist or socialist-feminist frameworks. Thinkers like Nancy Fraser, Cinzia Arruzza, and Tithi Bhattacharya advanced a Marxist-feminist analysis that treats class, gender, and race as interlocking systems rather than isolated issues. Their influential manifesto Feminism for the 99% (2019) exemplifies this synthetic approach, calling for an anti-capitalist feminism that rejects both class reductionism and liberal “lean-in” feminism. Such efforts show North American Marxist theorists pushing the tradition to grapple with the “matrix of domination” – the intersecting oppressions of capitalist society.

North America also contributed significantly to Marxist feminist theory in the form of Social Reproduction Theory (SRT). Scholars and activists (many in the U.S. and Canada, often working with European allies) revisited questions of unpaid domestic labor, care work, and the reproduction of labor power – issues first raised by Marxist feminists in the 1970s. The 2017 collection Social Reproduction Theory, for example, mapped how activities traditionally performed by women (child-rearing, housework, caregiving) are foundational to the capitalist economy, even though they are unpaid. By conceptualizing these activities as part of the “production of life” necessary for production of goods, SRT has expanded Marxist philosophy’s understanding of labor and value. This has led to new analyses of how capitalism relies on gendered and racialized divisions of labor, aligning with intersectional critiques. As one commentator noted, many feminists in the 2010s “re-engag[ed] Marx’s ideas in the face of global economic crisis and the dismantling of social programs,” seeing his framework as crucial for understanding how austerity and neoliberalism exacerbated gender oppression.

Meanwhile, the general public climate in the United States saw terms like “socialism” lose some of their Cold War stigma, partly due to the 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders and the growth of organizations like the Democratic Socialists of America. Although these are political developments, they influenced Marxist philosophical discourse by bringing classic concepts (class struggle, capitalism’s contradictions) to new audiences and energizing young scholars. Journals such as Monthly Review, Science & Society, and Capital & Class continued to provide venues for Marxist analysis, often bridging academic and activist concerns. Canadian political economists (e.g., Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, until Panitch’s death in 2020) wrote about the crisis of global capitalism and the prospects for socialist renewal. In the cultural realm, Marxist literary criticism and media analysis remained vibrant: for example, the late Mark Fisher’s concept of “capitalist realism” (though introduced in 2009) became a touchstone for many examining why it seems so hard to imagine alternatives to capitalism. Fisher’s work, along with Fredric Jameson’s continuing output on culture and Marxism, kept the Marxist critique of ideology in the spotlight.

Overall, in North America the last decade’s Marxist philosophy has been marked by a fusion of traditional Marxist political economy with critical theories of race, gender, and culture. This blending has arguably produced a more nuanced Marxism that addresses the lived experience of oppression in its multiple forms. It also generated internal debates (class-first vs. intersectional approaches) that have, on the whole, broadened the scope of Marxist theory and made it more relevant to contemporary social movements for racial, gender, and economic justice.

Latin America: Decolonizing Marxism and “21st Century Socialism”

Latin America’s Marxist intellectual tradition has been deeply shaped by the region’s history of colonialism, dependency, and revolutionary movements. Between 2015 and 2025, Latin American Marxist philosophy continued to evolve through engagement with indigenous perspectives, anti-imperialist thought, and the practical experiences of left-wing governments. A defining trend was the ongoing project of “Socialism of the 21st Century,” a model associated with the late Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and his allies during the “Pink Tide” of leftist governments. While the political fortunes of the Pink Tide rose and fell in this decade (with setbacks in countries like Brazil and Venezuela, and new left governments in Mexico and elsewhere), the ideas behind 21st-century socialism were actively discussed and theorized. These ideas emphasized democratic participation, regional integration, and the blending of Marxist economics with indigenous and nationalist traditions. For example, in Bolivia, Vice-President Álvaro García Linera – himself a prominent Marxist intellectual – wrote about merging Marx’s insights with the indigenous concept of ayllu (communal life) and what he termed the “communitarian” mode of production. Linera’s works in the mid-2010s analyzed how indigenous communal practices could interface with socialist policies, an attempt to indigenize and decolonize Marxist theory. Similarly, the concept of Buen Vivir (“good living”), drawn from Andean indigenous cosmologies, entered debates on development, suggesting alternatives to Western capitalist paradigms that Marxists engaged with. In this way, Latin American Marxism of the past decade often sought a synthesis between classical Marxist analysis and the pluricultural realities of the continent.

Latin American theorists also critically engaged with post-colonial and decolonial theory. While postcolonial theory (largely originating from South Asia and the Anglophone academy) sometimes distanced itself from Marxism, Latin America developed its own decolonial thought (with figures like Aníbal Quijano, Enrique Dussel, and Walter Mignolo) which both critiques Eurocentric narratives and, in some cases, builds on Marxist ideas of liberation. A noteworthy dialogue unfolded between Marxism and decoloniality: some scholars argued that Marxism needed decolonization (to shed Eurocentric assumptions), while others contended that decolonial theory underestimates the universal structures of capitalism that Marxism illuminates. This tension was visible in conferences and publications under the auspices of CLACSO (Latin American Council of Social Sciences) and journals like Latin American Perspectives. For instance, the debate sparked by Indian Marxist Vivek Chibber’s critique of Subaltern Studies (though focused on South Asia) resonated in Latin America, where questions of how global capitalist processes interact with local histories of colonialism remain central. Many Latin American Marxist philosophers reaffirmed that class analysis must integrate issues of imperialism, race, and indigeneity – a perspective rooted in the legacy of thinkers like José Carlos Mariátegui (Peru) and José Mariátegui’s East-South decolonial experiment. In practice, this meant examining, for example, how global capital exploits Amazonian resources (eco-extractive capitalism) and how indigenous communities resist, using Marxist concepts of primitive accumulation alongside indigenous rights frameworks.

Feminist currents in Latin American Marxism also flourished in the last decade. Marxist feminists played leading roles in mass movements such as the “Ni Una Menos” protests against gender violence that swept countries like Argentina after 2015. Intellectuals like Verónica Gago linked these movements to an anti-capitalist critique, arguing that neoliberal austerity and patriarchal violence are interconnected. Latin American socialist-feminist thought often stresses the coloniality of gender relations, blending insights from Marxism and decolonial feminism. Publications and gatherings (for example, the Latin American Feminist Encuentros) provided platforms for these ideas, which in turn influenced global discussions (the concept of a “feminism for the 99%” drew inspiration from Latin American strike tactics).

The influence of Latin American Marxist philosophy was felt beyond the region as well. European and North American leftists looked to Latin America for inspiration on how to build mass socialist movements in the 21st century. The writings of the late Marta Harnecker (Chilean Marxist theorist, d. 2019) – such as A World to Build – synthesized lessons from Latin American movements for an international audience, emphasizing grassroots empowerment and new forms of socialist democracy. Latin America’s experience also reactivated interest in dependency theory and world-systems analysis (traditions pioneered by thinkers like Raúl Prebisch, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and Immanuel Wallerstein). Updated dependency analyses examined China’s growing role in Latin America, raising questions of whether this constituted a new imperialism or “South-South” solidarity – a debate where Marxist economists and political theorists took contrasting views.

In summary, Latin American Marxist philosophy (2015–2025) can be characterized by its decolonial Marxist flavor and the praxis-oriented theorizing of socialism. Key figures blended Marxism with local knowledge and struggles, thereby expanding Marxist theory’s understanding of culture, colonial history, and ecology. This region demonstrated how Marxism could be reinvented to address questions of land, indigenous rights, and sovereignty, enriching the global Marxist tradition with new ideas of liberation and communal life.

Asia: Marxism in Transformation

Asia’s landscape of Marxist philosophy over the last decade has been dominated by the continued prominence of officially socialist states and the dynamic discussions within and around them. In China, Marxist theory holds an official place as state ideology, but in recent years it also became an arena of intellectual activity with global implications. Under President Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party explicitly reaffirmed its commitment to Marxism, not just as dogma but as a living analytical tool. At a high-profile conference in Beijing marking Marx’s 200th birthday in 2018, Xi declared Marxism a “powerful ideological weapon” for understanding and changing the world, urging Chinese scholars to “continuously improve the ability to use Marxism to analyze and solve practical problems.” This period saw Chinese academia invest heavily in Marxist research institutes and host international gatherings. The World Congress on Marxism, organized by Peking University, was held in 2015 and again in May 2018 (timed with Marx’s bicentenary), attracting hundreds of Marxist scholars from around the globe. The themes ranged from classic textual analysis of Marx to discussions of “Marxism and contemporary capitalism” and “Marxism and the mission of contemporary youth.” These congresses signaled China’s emergence as a hub for Marxist philosophical dialogue, bridging Chinese Marxist traditions with global currents. Chinese Marxist philosophers and social scientists engaged in debates about how to adapt Marxism to China’s rapid development and new challenges – for instance, how to address environmental degradation and inequality within a “socialist market” framework. They also explored Marxist approaches to technology and automation, given China’s leading role in AI and big data. Some Chinese theorists argued that Marxism must innovate to guide China in the “New Era,” integrating Marx with ancient Chinese philosophies or with Xi Jinping’s political thought. While these efforts are sometimes dismissed in the West as party propaganda, they do involve genuine philosophical exploration, evidenced by a growing body of Chinese-language Marxological scholarship and even experimentations like interest in Western Marxists (Gramsci, Althusser, etc., many of whose works have been translated and debated in China).

Outside China, other parts of Asia have had vibrant Marxist engagements as well. In India, Marxist philosophy intersected with the country’s unique social issues, especially caste. Intellectuals and activists on the left wrestled with how to unite Marx’s class analysis with Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s critique of the caste system. This gave rise to attempts at theoretical synthesis sometimes termed “Dalit Marxism” or at least a shared platform between Marxists and Ambedkarites. The debate was sharp: some Ambedkarite scholars accused Marxists of economic reductionism regarding caste, while some Marxists argued that caste oppression is intrinsically linked to material relations in semi-feudal capitalism. New works examined what Indian revolutionaries like Charu Mazumdar or EMS Namboodiripad might have missed about caste, and conversely, what Marxist method could reveal about modern caste dynamics. Academic journals (for example, Economic & Political Weekly) and left publications featured discussions on caste, class, and capitalism, indicating a richer Marxist social analysis emerging in South Asia. India’s strong tradition of Marxist political economy (e.g., the work of Prabhat Patnaik and Utsa Patnaik, who in 2016 published a new Theory of Imperialism) continued as well, often focusing on global finance and agrarian distress. The Patnaiks’ work sparked debate on whether classic imperialism theory (à la Lenin) can explain contemporary globalization, a question highly relevant for Asia’s post-colonial economies.

Elsewhere in Asia, Marxist philosophy in Japan and South Korea maintained a lower profile but persisted in academic circles – for instance, Japanese scholar Kohei Saito made an international impact with his award-winning book Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism (2017), which revisited Marx’s late notebooks to argue that Marx became increasingly ecological in outlook. Saito’s subsequent popular book Capital in the Anthropocene (2020, in Japanese) became a surprise bestseller, reflecting a hunger for anti-capitalist ecological theory in Japan. In the Middle East, Marxist ideas faced a more challenging environment amid conflicts and authoritarian crackdowns, yet they survived in niches. The Syrian crisis and other upheavals weakened organized left movements, but Kurdish regions (notably Rojava in northern Syria) drew on a blend of Marxist and anarchist ideas influenced by Murray Bookchin and Abdullah Öcalan to forge a experiment in “democratic confederalism” – essentially a libertarian socialist governance model. Though not Marxist in a doctrinaire sense, this represented a Marxian impulse to radically reimagine social relations in the midst of struggle.

On the margins of Asia, the case of Nepal stood out earlier in the decade: a Maoist-inspired party briefly led the government after 2006–2008, showing how Marxist-Leninist thought adapted to electoral politics. By 2015 this experiment had moderated, but Nepali Marxist intellectuals reflected on what it meant to carry out a communist revolution through ballots rather than bullets, contributing to broader Marxist debates on strategy. And in Southeast Asia, countries like Vietnam continued official Marxist-Leninist education; Vietnamese theorists quietly debated updating Marxism to guide economic reform while retaining socialist commitments.

In summary, Asia’s Marxist philosophical trends in 2015–2025 reveal a spectrum: from China’s state-supported yet globally engaged Marxist revival, to South Asia’s fusion of Marxism with anti-caste and anti-imperialist thought, to various localized adaptations. Marxism in Asia often had to address “combined and uneven development” – rapid industrialization, lingering pre-capitalist social forms, and geopolitical tensions – leading to innovative theoretical responses. Crucially, Asia also hosted significant Marxist events (like the World Congresses in Beijing) that have become new reference points for Marxist scholars worldwide, underlining that the center of gravity for Marxist philosophy is no longer confined to the West.

Intersectional and Critical Syntheses: Marxism Meets Feminism, Race, and Post-Colonialism

One of the most important developments in Marxist philosophy over the last decade has been its deepening intersections with other critical theories. Rather than standing apart, contemporary Marxism often engages in dialogue with feminism, critical race theory, and post-colonial thought. This intersectional turn has enriched Marxist theory, making it more attuned to multiple forms of domination and their interrelation with class exploitation. As noted, North American and European Marxist-feminists have foregrounded social reproduction and gendered labor. Globally, an ethos of Feminism for the 99% has connected the Marxist critique of capitalism with the feminist critique of patriarchy. Thinkers like Nancy Fraser argued that capitalism harbors multiple “hidden abodes” of production and maintenance – not only the factory or office, but also the home and community – where unpaid or underpaid labor (often by women or marginalized groups) sustains the system. This perspective updated Marx’s theory by incorporating caregiving and affective labor into an expanded understanding of exploitation. It also reframed emancipatory politics: socialism and women’s liberation are seen as mutually constitutive projects. The global women’s strike movements (2017–2020) echoed these theories on the streets, demanding recognition that “women’s work” is work – effectively a mass Marxist-feminist assertion.

In engaging critical race theory (CRT) and post-colonial perspectives, Marxism had to confront its historical blind spots regarding hierarchy and identity. CRT’s focus on systemic racism prompted Marxists to investigate how racial categorizations have been woven into capitalist social relations since the very beginning (from slavery to colonial plunder). The concept of racial capitalism gained prominence as a framework synthesizing these views. This line of thought, influenced by Cedric Robinson and W.E.B. Du Bois before him, suggests that capitalism did not emerge in a color-blind way but was formatively shaped by racial oppression; hence any analysis of capital that ignores race is incomplete. Contemporary Marxists such as David Roediger and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor extended this analysis to issues like mass incarceration and housing discrimination, illustrating how racialized super-exploitation generates surplus value and upholds class rule. On the other hand, Marxist critics of identity politics cautioned against what they perceived as a fragmentation of struggle. The resulting debate – sometimes termed the “class vs. race debate” – has in fact produced more nuanced theory: many now advocate a “both/and” approach recognizing class, race, and gender as “mutually constructing” forces. In academic journals and left conferences, terms like “conjugated oppression” or “interlocking oppressions” were used to theorize how, for instance, a black working-class woman experiences capitalism in a way that cannot be reduced to a single axis of analysis.

Post-colonial theory posed a different kind of challenge: it critiqued Eurocentrism and questioned universal narratives, including those in orthodox Marxism. In the 2010s, a notable dialogue (and at times dispute) occurred between Marxists and post-colonialists. Marxists like Vivek Chibber argued that certain strands of post-colonial theory (e.g. Subaltern Studies) relapsed into cultural relativism and ignored the common coercions of capitalism. Post-colonial scholars countered that Marxism had traditionally overlooked how colonial contexts alter class formation and that concepts like modernity and progress needed decolonizing. The synthesis emerging from this back-and-forth is a more reflexive Marxism, one aware that the “underdevelopment” of the Global South is not a stage but a result of imperialist extraction and that revolutionary subjects may form along axes not strictly defined by industrial class. The decolonial Marxist currents in Latin America (as discussed) exemplify this blending: they use Marxist analysis of political economy while rejecting Eurocentric assumptions, insisting on the specificity of historical contexts. Even within European academia, the influence of post-colonial critiques pushed Marxist scholars to revisit colonial history’s impact on Marx’s own writings and to integrate insights from scholars of the Global South. We see, for example, Marxist historians revisiting anti-colonial Marxists like C.L.R. James, Frantz Fanon, or Amílcar Cabral for theoretical inspiration, effectively broadening the Marxist canon to be more globally representative.

In short, the intersections of Marxism with feminism, race theory, and post-colonialism have generated new theoretical frameworks sometimes labeled as “intersectional Marxism”, “Marxist feminism”, or “postcolonial materialism.” These frameworks maintain Marx’s focus on capitalism’s social relations of production while shedding the reductionist tendencies that sidelined issues of identity and culture. The result is a Marxist philosophy more equipped to analyze the “totality” of domination – economic, social, and cultural – in contemporary global society. This intersectional enrichment has also made Marxist thought more accessible and relevant to activists in movements against racism, sexism, and colonial legacies, thereby increasing its practical impact on discourse beyond academia.

Marxism and Ecological Thought: Ecosocialism in the Anthropocene

Perhaps the most urgent new dimension of Marxist philosophy in the past ten years has been its engagement with ecological thought. As climate change and environmental crisis became defining issues of the era, Marxist theorists sought to understand the ecological dimensions of capitalism and articulate a vision of ecosocialism. A major development was the revival and expansion of Marx’s concept of the “metabolic rift.” Originally derived from Marx’s notes on soil fertility and capitalist agriculture, the metabolic rift theory (pioneered by sociologists John Bellamy Foster, Paul Burkett, and others) describes how capitalism ruptures the natural metabolic interaction between humans and the earth. In the 2010s, this theory reached a “highest stage of eco-Marxology” with works like Marx and the Earth (Foster & Burkett, 2017), which meticulously defended Marx’s ecological insights and countered critics who claimed Marxism was “productivist” or anti-environment. Foster and colleagues argued that Marx’s analysis of capitalism inherently includes an ecological critique – his notion of capitalism’s unsustainable raids on nature via the separation of producers from means of production translates directly into modern concerns about soil depletion, biodiversity loss, and carbon emissions.

At the same time, a vigorous debate emerged between different schools of Marxist ecology. On one side stood the metabolic rift school associated with Foster, which emphasizes specific rifts (such as the carbon rift, nutrient rift, etc.) opened by capitalist processes. On the other side, scholars like Jason W. Moore proposed an alternative framework called “world-ecology.” Moore contends that capitalism is a world-ecology – a single, unified process that encompasses “oikOS” (household, which he uses to mean nature) and economy together. He criticized the metabolic rift concept for, in his view, maintaining a Cartesian separation of “Nature” and “Society.” By 2017, debates in ecological Marxism “to a great extent revolve[d] around the figure of Jason W. Moore” challenging the orthodox metabolic rift paradigm. Moore’s Capitalism in the Web of Life (2015) and subsequent exchanges sharpened the discussion: Are ecological crises best understood as ruptures in natural cycles caused by capitalism’s logic (the rift), or as a cumulative reordering of humans-nature as one bundle (world-ecology)? This debate, though technical, pushed Marxist philosophy to grapple with issues of systems theory, complexity, and how to conceptualize the Anthropocene (the proposed geologic age of human influence on Earth). It also engaged non-Marxist ecological thinkers, making Marxist concepts part of broader environmental theory conversations.

Alongside these theoretical debates, Marxist philosophy became increasingly entwined with climate activism and policy discussions. The idea of ecosocialism – a socialism that is ecologically sustainable and confronts the climate crisis – gained currency. Major books by Marxist authors addressing climate politics appeared, such as Andreas Malm’s Fossil Capital (2016) which historically linked the steam age’s reliance on coal to the imperatives of capitalist competition, and later Malm’s Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency (2020) addressing the urgency of radical action (even sabotage) against fossil fuel infrastructure. Malm and others argued that only by overthrowing capitalism’s drive for endless growth could climate catastrophe be averted, a claim that gave philosophical backbone to the slogan “System Change, Not Climate Change.” Journals like Monthly Review and Capitalism Nature Socialism featured extensive discussions on topics like renewable energy under socialism, the concept of a “just transition” for workers, and the compatibility (or not) of degrowth ideas with Marxism. Notably, Japanese Marxist Kohei Saito’s work introduced the provocative thesis that Marx had become a “degrowth communist” in his final years – suggesting that Marxist strategy in the 21st century might involve intentionally scaling down production to restore ecological balance. While not all agreed, this marked a new frontier: Marxist philosophy directly engaging with concepts of limits, planetary boundaries, and post-growth economics.

The influence of Marxist ecological thought also extended into political forums. In the late 2010s, the Green New Deal proposals in the US and Europe, while not explicitly Marxist, drew on analyses of capitalism’s systemic relation to environmental destruction, influenced in part by left intellectuals. Conversely, some conservative critics began attacking “ecosocialism” and even “cultural Marxism” as supposed threats, which ironically brought more attention to Marxist analyses of climate. Within the Marxist left, ecological issues ceased to be secondary; almost every major Marxist conference or publication by 2025 included a climate component. This is a profound shift from earlier decades where productivist tendencies sometimes led socialists to downplay ecology. Now, the consensus among Marxist philosophers is that any viable socialism must integrate ecological sustainability at its core. In Marxist terms, the forces of production now include understanding Earth systems, and the relations of production must be transformed not only for social justice but for ecological harmony.

In summary, Marxist philosophy’s encounter with ecological thought in the past decade has been transformative. It brought back to light Marx’s own writings on nature and prompted creative extensions of his theory to the climate crisis. It led to new syntheses like ecofeminist Marxism (highlighting how ecological degradation and the oppression of women share roots in capitalist patriarchy) and discussions of indigenous ecological knowledge within Marxist anti-colonial frameworks. The urgency of the climate challenge has, in a sense, rejuvenated Marxist philosophy – giving it a pressing mission to envision a sustainable civilization beyond capitalism. As one commentator put it, Marxism today provides “a holistic vision of the socialist/communist future that is best described as one of sustainable human development” , uniting red and green into a single critique and praxis.

Conclusion

Over the last ten years, Marxist philosophy has proven to be remarkably dynamic and globally diverse. Far from being a relic of the 19th or 20th centuries, Marxist theoretical work from 2015 to 2025 shows a living tradition responding to new conditions. In Western Europe and North America, economic crises and social movements breathed new life into Marxian analysis, even as thinkers revised it through lenses of gender, race, and technology. In Latin America and parts of Asia, Marxism intertwined with anti-colonial and indigenous ideas, yielding novel syntheses like 21st-century socialism and decolonial Marxism that expand the horizons of materialist theory. Across all regions, intersections with feminism, critical race theory, and ecology have challenged Marxist philosophers to address capitalism not as an isolated economic system but as a totality affecting all aspects of life and the planet. Major publications and conferences during this period – from Feminism for the 99% to world congresses in Beijing – symbolized a reinvigorated discourse, one that is at once more nuanced (incorporating multiple oppressions) and more urgent (confronting existential threats like climate change).

A key feature of Marxist philosophy in this decade is plurality. No single “correct” Marxism dominates; instead, we see an array of schools: neo-Marxian humanism, Marxist feminism, Afro-Marxism, eco-Marxism, analytical and heterodox Marxism, among others, all contributing insights. This pluralism has led to healthy debates – sometimes contentious, but often illuminating. Issues of strategy (reform vs. revolution, party vs. horizontalism) and theory (economism vs. intersectionality, metabolic rift vs. world-ecology) were vigorously argued. Such debates indicate a tradition very much alive, contesting and reinventing itself. Importantly, Marxist philosophy has also maintained a dialogue with practice: many of the theorists discussed are directly involved in social movements or derive inspiration from them. This ensures that the philosophy does not drift into pure abstraction but remains, in Marx’s own spirit, a critique of society aimed at its transformation.

In conclusion, the period 2015–2025 has seen Marxist philosophy both deepen and broaden. It has deepened by refining core concepts (like class, value, ideology) in light of contemporary developments, and broadened by reaching into new domains (identity, ecology, digital technology) and new geographical contexts. The influence and contributions of the figures and schools surveyed here demonstrate Marxism’s enduring capacity to illuminate the world – and to imagine it otherwise. As we move forward, this rich body of Marxist thought will continue to be a vital resource for scholars and activists seeking to understand and change a world still very much shaped by the forces Marx diagnosed, even as it is convulsed by challenges he could only dimly foresee. In that sense, the major trends of the last decade affirm that Marxist philosophy remains, in a famous phrase, a “weapon for change” as well as interpretation, continually reinventing itself to grasp the complexities of the present and the possibilities of the future.

Leave a comment