An ongoing series of reflections on Marxist economics after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

Let us begin, if we may, with the impolite but inescapable observation that the world, as we encounter it, is built upon layers of deception so nuanced they have become indistinguishable from the architecture of reality itself. Among these deceptions, few are as entrenched—and as crucial—as the mythologies we construct around value. Here, in the grimy intersection between money and morality, between production and power, we find Karl Marx wielding his dialectical scalpel with typical severity, exposing the mechanisms by which capitalism distorts human labor into abstract equivalence.

At the core of Marxist economics lies the labor theory of value—not a terribly fashionable phrase in the drawing rooms of contemporary neoliberalism, but one that remains insistent in its explanatory power. Marx, unlike the apologists for market spontaneity, did not believe value was generated by mere desire or scarcity. These are convenient euphemisms deployed by the owning classes to conceal the naked exploitation embedded in capitalist exchange. Instead, Marx asserted that the value of a commodity is determined by the socially necessary labor time required to produce it.

Now, within this foundation lies a critical distinction: that between absolute and relative surplus value, which are not merely economic categories but, if one reads Marx with a sufficiently dialectical eye, mechanisms of domination—of time, of life, of the very soul of the worker.

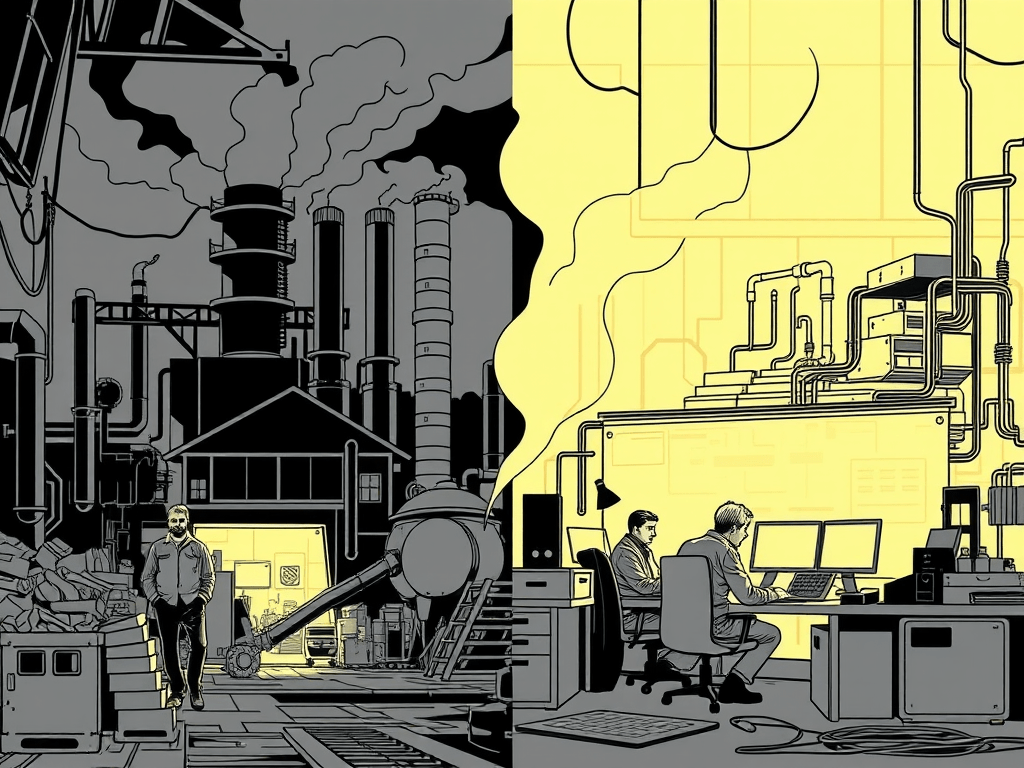

Absolute surplus value is the more blunt of the two instruments. It refers to the surplus extracted by simply extending the working day. If you can wring ten hours of labor out of someone instead of eight, with no increase in pay, the difference is profit—pure, uncut exploitation. This method of accumulation, familiar to any child who has read Oliver Twist or worked in an Amazon warehouse, is as old as wage labor itself.

Relative surplus value, on the other hand, is a sleight of hand more worthy of admiration if one were inclined to applaud the ingenuity of thieves. It emerges not by lengthening the day but by intensifying productivity—through technology, division of labor, and efficiency gains. The working day stays the same, but the worker produces more, and the capitalist reaps the surplus. It is here that modern capitalism dons its digital mask and speaks the language of innovation, all the while intensifying exploitation with a smile.

These two forms of surplus value are not merely economic strategies but ideological weapons. The extraction of absolute surplus value thrives under conditions of overt coercion—slavery, child labor, sweatshops. Relative surplus value, by contrast, cloaks itself in the rhetoric of progress, allowing the system to masquerade as meritocracy. It is the difference between the whip and the algorithm, though the lash remains intact in many parts of the world.

Now, what of value itself? Is it absolute, as some naïvely hope, or relative, as postmodern capitalists suggest? Marx would have us understand that value is socially constructed but not subjectively whimsical. It is objective within a historical and social context—rooted in labor, not in sentiment. This is where Marxist economics departs most radically from the market evangelism of neoclassical economics. The latter treats value as an emanation of individual preference—as if taste alone could mint currency. Marx saw this for what it is: ideology masquerading as science, a way to naturalize inequality by pretending that price and value are synonymous.

In this sense, the relative nature of value under capitalism becomes a mask for absolutes—not of worth, but of power. The capitalist class reconfigures society to maximize its ability to extract value from labor, thereby creating a shifting terrain where what is valued, and how, is a reflection not of intrinsic worth but of exploitative necessity. Diamonds are expensive not because they are rare, but because they are hoarded. Software engineers are paid more than nurses not because they are more vital, but because their labor is more profitable.

The beauty—and the horror—of Marx’s insight is that value is not merely a number attached to a commodity; it is a reflection of class struggle. What appears on a price tag is not a neutral datum but a battlefield.

And so, when we ask whether value is absolute or relative in Marxist economics, we are in fact asking a more subversive question: who decides what is valuable, and why? To answer this is to interrogate the foundations of the society in which we live. It is to recognize that capitalism, for all its talk of freedom, defines value in such a way that freedom becomes the exclusive property of those who own the means of production.

That Marx gave us a language for this inquiry is itself a kind of intellectual liberation. Whether we act on it—or sell it for a consultancy fee—is another matter entirely.

Leave a comment