In the long catalog of capitalism’s ironies, “under-consumption” deserves a special entry. This dry term signifies nothing less grotesque than people going without what they need because too much has been produced that cannot be profitably sold. It is the spectacle of want amid plenty – a cyclical absurdity where factories burst with commodities while families struggle to afford mere necessities. Marxist economics treats this not as a mere accident or a moral failing of the poor, but as a systemic paradox. As Marx and Engels noted of capitalist crises, society finds itself assailed by an “epidemic” of overproduction that “in earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity – the epidemic of over-production”. Indeed, imagine explaining to a starving peasant of an earlier century that future markets would collapse because too much bread was made! Yet under-consumption – poverty in the midst of plenty – has become a recurrent theme of modern history, demanding an explanation sharper than the bromides of classical economics.

Mainstream economists once denied such a scenario was even possible. Say’s Law optimistically assured us that supply creates its own demand – that every seller finds a buyer, by definition. If people are hungry, why, markets must eventually feed them; general gluts cannot occur. But reality has made a mockery of these assurances. From the Great Depression to the 2008 crash, capitalism has repeatedly produced more than it could sell, then blamed the resulting slump on people’s mysterious failure to consume. In effect, the magnates of industry cry out in bafflement that the peasants are not eating the feast that was never within their reach. One hears echoes of Marie Antoinette’s apocryphal “let them eat cake” – except today the suggestion is to buy the cake on credit. Under-consumption, in Marxist terms, isn’t a fit of mass frugality or a dietary preference; it is a built-in outcome of an economy that pays workers too little to buy back the mountain of goods they themselves produce. As we shall see, what under-consumption is “really” caused by, according to Marxist theory, is this very contradiction – a system that demands endless growth yet ensures that the majority cannot afford to consume that growing output. The prose of Marx may be dense, but the moral indictment is simple: a society that can churn out abundance but cannot distribute it except to those with money is one perched on a precipice of its own making.

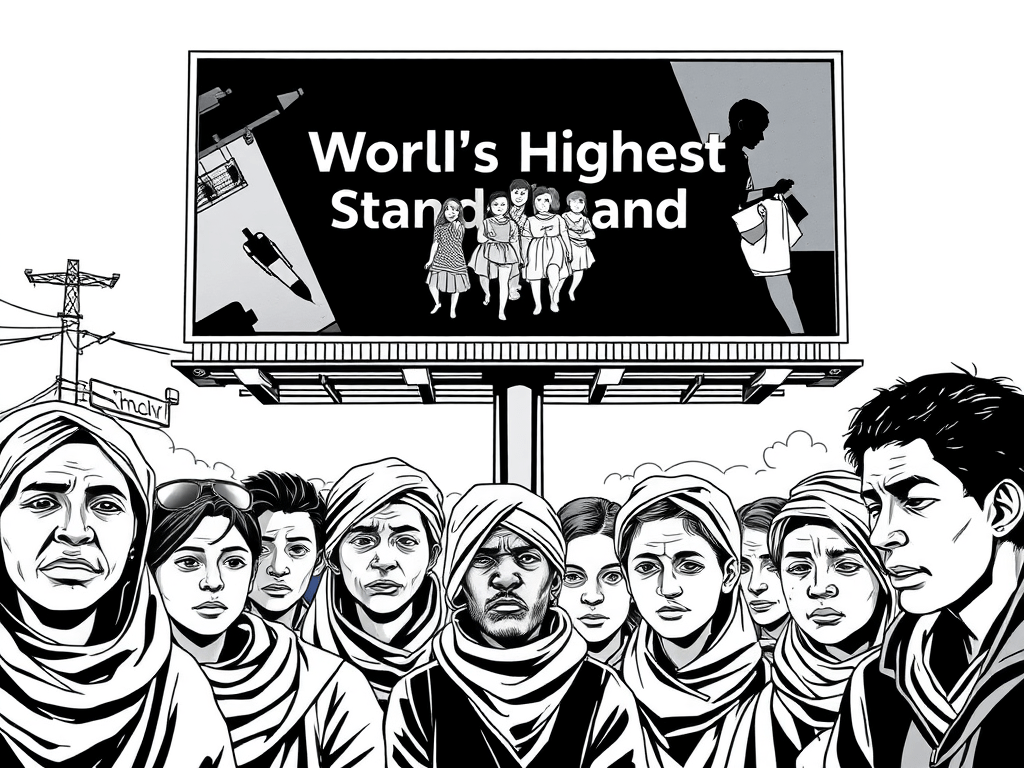

Poverty Amid Plenty

In an iconic 1937 photograph by Margaret Bourke-White, African American flood victims queue for food relief beneath a billboard proclaiming “World’s Highest Standard of Living – There’s no way like the American Way.” The striking contrast between the smiling, well-heeled white family on the advertisement and the grim faces in the breadline illustrates the dissonance of under-consumption: prosperity is vaunted in theory, even as poverty prevails in reality.

History offers no shortage of such images and episodes. During the Great Depression, warehouses and silos overflowed even as soup kitchens swelled. In one notorious policy, the U.S. government paid farmers to slaughter livestock and plow under crops in order to reduce supply and prop up prices – literally creating scarcity in the midst of hunger. Millions of hogs were killed and cotton fields destroyed under the Agricultural Adjustment Act, at the very moment millions of Americans were underfed. It is an enduring, near-surreal facet of capitalist crisis that relief for poverty is sought by orchestrating more poverty: food is dumped into the ocean or left to rot so that it never reaches those who can’t pay. As one commentator summarized, the only problem was not supply – there was “enough food to feed every man, woman, and child” – the problem was that the hungry simply lacked the money to buy it. This pattern is so deep-rooted that it reappeared in the 21st century. In the spring of 2020, with a pandemic causing sharp drops in restaurant demand, American farmers found themselves dumping milk, smashing eggs, and plowing vegetables back into the soil. Meanwhile, miles-long lines formed at food banks. In the richest country on earth, hunger was not due to a lack of food, but to that food being “excess” from the perspective of profit. The moral paradox could not be starker: capitalism can ensure that food is plentiful, or people are fed – but, tragically, not always both at the same time.

Under-consumption is thus not a hypothetical abstraction; it has been the lived reality of countless crises. Time and again the system produces more goods than the market (i.e. paying customers) can absorb, and the result is calamity. Factories shut down because inventories back up. Workers are laid off because they produced too much for their own paychecks to buy back. The victims are then chastised, implicitly or explicitly, for not spending enough! In moments of crisis, it is not uncommon to see editorialists implore consumers to do their “patriotic duty” and shop more – as if the fault lay in the public’s inexplicable austerity, rather than in their very real lack of income. The irony would be laughable if it were not so cruel. This blame-the-victim narrative was skewered over a century ago by Friedrich Engels, who remarked that it requires “a strong dose of deep-rooted effrontery” to explain an economic slump by “the under-consumption of the masses and not by the overproduction carried on by the… mill owners”. Engels knew well that the restriction of the masses’ consumption was no accident – it was the inevitable flip side of how those very mill owners did business.

Various makeshift “solutions” have been attempted to paper over the under-consumption problem, none addressing its root cause. For example, capitalists historically sought new markets abroad for their excess goods – a drive J. A. Hobson identified as a key motive for imperialism, resulting from domestic masses being kept too poor to consume the surplus . In more recent times, the system turned to credit expansion: when wages stagnated, consumer debt was encouraged to artificially prop up demand. By the early 2000s, an “unprecedented expansion of consumer credit” coincided with stagnant middle-class wages, masking the gap between what people needed and what they could afford. This only delayed the reckoning and made the crash of 2008 more devastating when debts could no longer be repaid. At other times, governments have resorted to wasteful spending or destruction of surplus (as in the New Deal farm policies) and even war production to absorb excess capacity. All these measures treat the symptoms – too many goods, not enough buyers – but tiptoe around the underlying malady. The persistence of such stopgaps merely underscores the Marxist point: under-consumption is not caused by fickle consumer tastes or some sudden prudish refusal to buy, but by structural constraints that capitalism itself imposes.

The Contradiction at the Core

What, then, does Marxist theory identify as the true cause of under-consumption? In a word, capitalism’s own DNA – its core dynamic of profit and exploitation. Under-consumption is ultimately a byproduct of the system’s defining contradiction: the “unlimited drive to produce” versus the “limited consumption of the masses”. Capitalist enterprises must ceaselessly expand output in pursuit of profit; yet they simultaneously limit the purchasing power of the very workers and consumers expected to clear that output. The reason is straightforward – and damning. Profit, as Marx analyzed, comes from paying workers less than the value of what those workers produce. In Marx’s labor theory, only human labor creates new value; the capitalist, by design, withholds a portion of that value as surplus (profit), paying the worker only a wage covering basic needs. Thus “the working class receives in wages less [value] than they produce”, and this unpaid labor is appropriated by capital as profit. The immediate consequence is that workers (the vast majority of society) can never buy back the full fruit of their labor. They simply aren’t paid enough. Overproduction and under-consumption are two sides of this coin: capital piles up goods for sale, while the impoverished masses, restricted to what is necessary for their upkeep, inevitably fall short as customers.

To be clear, Marx and Engels did not invent the observation that the poor can’t afford much; what they provided was a theory of why this becomes a crisis under capitalism. After all, as Engels pointed out, the “under-consumption of the masses…has existed as long as there have been exploiting and exploited classes.” Peasants and serfs through history lived on the edge of subsistence – yet feudal or ancient societies generally suffered scarcity crises (crop failures, etc.), not crises of market glut. Under-consumption alone is not new; what is new is its collision with the modern engine of production-for-profit. Capitalism is uniquely productive – it can flood the world with yarn, steel, cars, you name it – but it is also uniquely anarchic. Production is not planned to meet human need; it is organized to chase exchange-value and profit. As a result, there is no guarantee that what is produced can be sold. People need the goods, certainly – but need doesn’t pay the bills. They “lack ‘effective demand’, to use the bourgeois economists’ term”, meaning they lack the cash to back up their needs. Thus we witness the “strange phenomenon” of overproduction: plenty of food, clothes, houses, yet masses of unmet needs. The market only recognizes demand with money behind it, not hunger or desire in the abstract. Marx tersely noted that to say a crisis is caused by insufficient consumption is a tautology – it tells us nothing new, merely restating that unsold goods found no buyers. The real question is why they found no buyers. And the Marxist answer lies in those lopsided class relations: capital’s profit-driven suppression of wages and its compulsion to expand production without regard to real social limits.

At the heart of under-consumption is this mismatch between production and distribution. Capitalism periodically saws off the branch on which it sits: it cranks up output, exploits workers to the hilt to do so, and in the process keeps those workers (and much of society) too poor to purchase the output. The system, figuratively speaking, invites everyone to a grand banquet of commodities but sells tickets only to the wealthy. It then acts surprised when the banquet hall isn’t full. Each capitalist, in isolation, behaves “rationally”: to maximize profit, they squeeze wages, cut costs, boost productivity. But collectively these actions have the irrational result of eroding the market for everyone’s goods. As Engels explained, “The capitalists as a whole naturally want an expanding market. Each individual capitalist would be delighted if all other capitalists raised their workers’ wages – yet when it comes to his own workers, he is determined to keep wages down”. The outcome is that all capitalists do the same, and thus demand is depressed economy-wide. In Engels’ pithy formulation, “The product governs the producers” – the creators of wealth find themselves at the mercy of a market they have collectively impoverished. It’s a classic case of what one might call capitalist folly: rational self-interest at the micro level leading to calamity at the macro level. No one decides to have a crisis, yet their fragmented pursuit of profit makes one inevitable. The system “creates and destroys the market at the same time” – creating it by developing productive forces, destroying it by impoverishing the majority.

Marx put it in plain words: “The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses” in the face of the system’s drive to expand as if only society’s absolute capacity to consume set a limit. In other words, capitalism behaves as if every person’s wants were backed by an infinite wallet, yet it operates in a way that keeps most wallets nearly empty. Sooner or later, this contradiction brings the whole frenetic dance to a halt – a crash, a glut, an economic heart attack. What follows is the familiar story: businesses collapse, unemployment soars, and suddenly everyone discovers what should have been obvious all along – that workers were also customers, and starving your customers is not a great business strategy. Only after the damage is done do the captains of industry clamor for someone (often the state) to stimulate “demand” again, to get the consumers consuming. It is a grand cosmic joke – except the joke is on those who can least afford it.

Marxist theory thus answers the riddle of under-consumption by turning it on its head. The issue isn’t that the masses won’t consume; it’s that they can’t, because the distribution of wealth under capitalism is fundamentally unjust and inefficient. Production is a social act – millions toil to create the world’s goods – but consumption is curtailed by private profit. The root cause of under-consumption is found in the wage relation itself and the class structure. Capitalism, by its very logic, must keep the lion’s share of wealth in the hands of a few (the capitalists) if it is to function; but that same logic undermines its ability to realize the value of what it produces. As a result, crises erupt. Under-consumption is capitalism reaping what it sows. It is not the hungry who cause the famine by not dining; it is the system that makes a feast of their labor while denying them a seat at the table.

One might say that under-consumption indicts capitalism on a charge of grand larceny against the human condition. Here is a system that congratulates itself on unprecedented productivity, only to turn around and chide the underpaid multitudes for not buying enough of the surplus. It is, at bottom, a sick joke: the couching of systemic theft as a problem of insufficient appetite. History’s verdict, delivered through each recurring crisis, is that this joke wears thin. No amount of advertising jingles or credit cards can forever paper over the reality that people do not deliberately starve themselves amid abundance – they are starved by the terms on which access to that abundance is granted. Under-consumption is therefore a kind of permanent background condition, punctuated by acute episodes that force society to confront the irrationality at its core. In every such episode, the same moral question presses forward: How long will we continue to tolerate an economy that condemns the many to deprivation because it cannot profit from satisfying their needs? Marxist theory, with its analysis of exploitation and class, shines a pitiless light on this question. It tells us that under-consumption is not a mysterious ailment or a failure of individual duty, but the predictable result of a system that has exhausted its moral and historical justification.

In conclusion, to interrogate what under-consumption is really caused by according to Marxist economics is to cast an unforgiving gaze at the very structure of capitalist society. It is caused by the profit motive overruling human need, by private accumulation sabotaging public abundance. Under-consumption, in the Marxist view, is nothing so banal as a dip in shopping enthusiasm; it is the symptom of a fatal contradiction, the hunger at capitalism’s banquet that will not be sated until the table is set on entirely different terms.

Leave a comment