My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

Early Life and Education

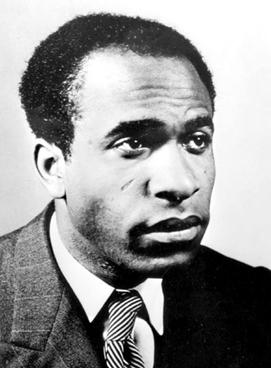

Frantz Omar Fanon was born on July 20, 1925, in Fort-de-France, Martinique, then a French colony. His family was part of the black middle class, and his father was a customs inspector. Fanon’s early exposure to French colonialism and racism—particularly during World War II when Martinique was governed by the pro-Vichy regime—deeply shaped his worldview.

At age 18, Fanon joined the Free French forces, fighting against fascism in the Mediterranean theater. After the war, he returned briefly to Martinique and then moved to France to study medicine and psychiatry at the University of Lyon. It was during his time in France that Fanon became increasingly involved in existentialist philosophy and was influenced by thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Aimé Césaire, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Psychiatry and the Algerian War

Fanon became a practicing psychiatrist and accepted a post at the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria in 1953. His work there, during the height of the Algerian War for independence, brought him face-to-face with the trauma of colonialism. He observed how both colonized patients and French colonial doctors were locked in a system of dehumanization.

Gradually, Fanon became actively involved in the Algerian liberation movement, joining the National Liberation Front (FLN). His experiences as a psychiatrist and revolutionary formed the basis of his most famous works, where he combined psychoanalysis, Marxism, and existentialism to understand the psychological effects of colonization.

In 1956, Fanon resigned from his hospital post, condemning French colonialism in a public letter. He was expelled from Algeria shortly thereafter and relocated to Tunis, where he wrote prolifically for El Moudjahid, the FLN’s newspaper, and served as an ambassador for the FLN in sub-Saharan Africa.

Major Works and Ideas

Black Skin, White Masks (Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952)

Written while still a student in France, this book examines the internalized racism and identity crises experienced by black people in a white-dominated world. Fanon analyzes the psychological impact of colonialism and racism, exploring how language, culture, and whiteness are wielded as instruments of domination.

The Wretched of the Earth (Les Damnés de la terre, 1961)

Fanon’s magnum opus, written during the last year of his life, is a revolutionary treatise that argues that decolonization must be violent, because colonialism itself is born and maintained by violence. The book addresses the role of the peasantry in revolution, the failures of the post-colonial bourgeoisie, and the need to forge a new humanism. Sartre’s incendiary preface further amplified the text’s revolutionary impact.

A Dying Colonialism (L’An V de la Révolution Algérienne, 1959)

This work details the transformation of Algerian society during the anti-colonial struggle, particularly in terms of gender, media, and medicine. Fanon illustrates how resistance reshapes not only political systems but also social and personal relations.

Toward the African Revolution (Pour la Révolution Africaine, 1964)

Published posthumously, this collection of essays and speeches reveals Fanon’s growing engagement with Pan-Africanism, anti-imperialist solidarity, and Third World internationalism.

Death and Legacy

Frantz Fanon died of leukemia on December 6, 1961, in Bethesda, Maryland, at the age of 36. He had traveled to the United States for treatment but succumbed shortly after arriving. Despite his early death, Fanon’s influence has been enormous.

Fanon’s work inspired anti-colonial and revolutionary movements across Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, and Asia. He became a foundational thinker for postcolonial studies and was deeply influential on figures like Amílcar Cabral, Steve Biko, Che Guevara, Malcolm X, and the Black Panther Party. In academic contexts, he remains central to debates in philosophy, race theory, psychology, and political theory.

Today, Fanon is recognized not only as a revolutionary theorist but as a moral voice of the 20th century, who dared to articulate the rage, dignity, and vision of the colonized in the face of global injustice.

Bibliography

Primary Works by Frantz Fanon

1. Black Skin, White Masks (Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952) – Translated by Charles Lam Markmann.

2. A Dying Colonialism (L’An V de la Révolution Algérienne, 1959) – Translated by Haakon Chevalier.

3. The Wretched of the Earth (Les Damnés de la terre, 1961) – Translated by Constance Farrington.

4. Toward the African Revolution (Pour la Révolution Africaine, 1964) – Translated by Haakon Chevalier.

Secondary Sources and Critical Studies

1. David Macey, Frantz Fanon: A Biography (Picador, 2000) – The definitive full-length biography.

2. Lewis R. Gordon, What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought (Fordham University Press, 2015).

3. Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (Routledge, 1994) – Includes critical readings of Fanon’s work in postcolonial theory.

4. Nigel C. Gibson, Fanon: The Postcolonial Imagination (Polity Press, 2003).

5. Sartre, Jean-Paul, “Preface” to The Wretched of the Earth (1961).

6. Irene L. Gendzier, Frantz Fanon: A Critical Study (Grove Press, 1973).

Leave a comment