An ongoing series of reflections on Marxist economics after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

The late Karl Marx, both an economist and a Victorian prophet of damnation, never failed to cast a long and accusatory shadow over the edifice of capitalism. Among his more enduring and controversial notions is the idea of the tendency in capitalist accumulation – that irresistible gravitation toward crisis, exploitation, and inevitable collapse. If one listens closely enough, one can almost hear Marx whispering to us from the grave, or perhaps shouting, as was more his habit.

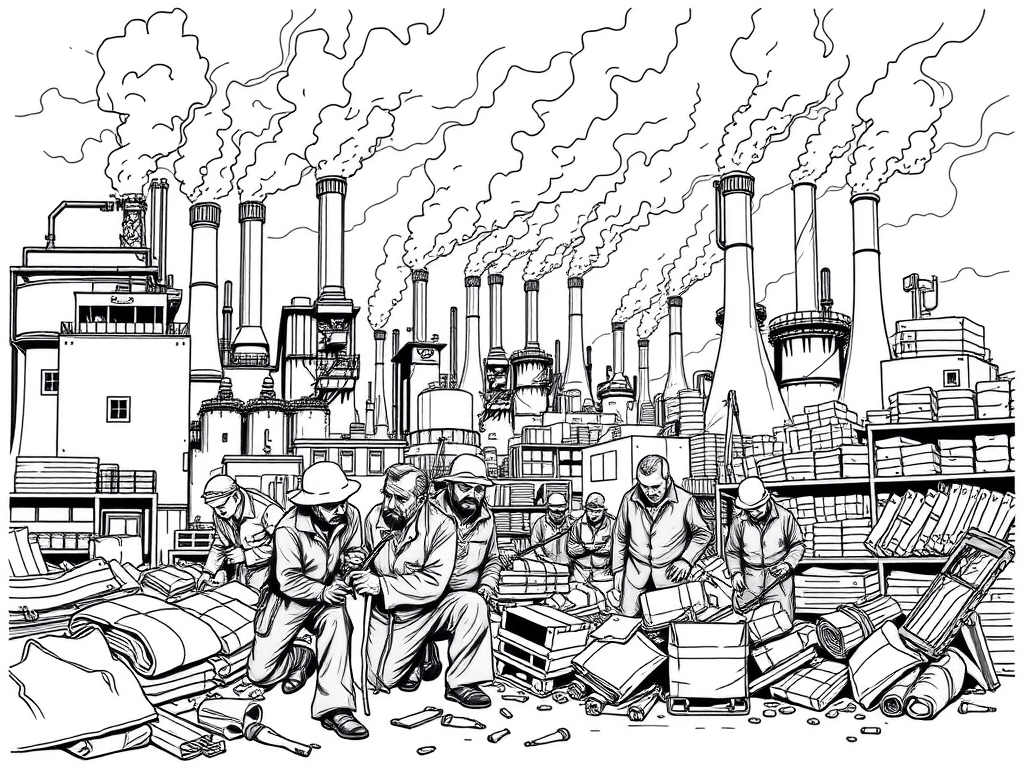

Marx posited that the very engine of capitalism – the accumulation of capital – would act as both its catalyst and its executioner. In his view, the capitalist, forever caught in the maniacal pursuit of profit, is condemned to reinvest surplus value (wrenched from the brow of the laborer) into the expansion of production. This isn’t philanthropy; it is the compulsory logic of survival in the marketplace. Accumulate or die. The consequence? A perpetual cycle of capital concentration, monopolization, and a swelling reserve army of labor. Capital chases capital; the big fish devours the small, and the proletariat is left to grovel on increasingly barren shores.

It is here that Marx the economist meets Marx the moralist. The tendency of capitalist accumulation is, in his schema, not merely an economic dynamic but a profound human tragedy, one measured in the ever-widening gyre of inequality and alienation. He envisions a system that, by its own laws, sharpens class antagonisms to the point of rupture. The capitalist mode of production sows the seeds of its own destruction, generating periodic crises of overproduction—ironically not due to scarcity, but to abundance. Factories overproduce; shelves overflow; workers, impoverished and underpaid, cannot afford to purchase the very goods they produce.

It is a sublime irony, or so Marx would have us believe, that the capitalist becomes the architect of his own ruin, forging chains as well as coins. And here one can almost hear Marx cackling at the apologists of free markets, those Panglossian devotees who imagine capitalism as a self-correcting, rational system. Yet even the dullest student of history cannot ignore the cyclical crises—the panics of 1873, 1929, 2008—that suggest there might be more to Marx’s grim prognosis than bourgeois economists would care to admit.

But let us be clear: Marx is not merely a Cassandra, doomed to be ignored by triumphant neoliberals. He is also, as Orwell shrewdly observed, an Old Testament figure, shaking his fist at the Golden Calf. One needn’t accept the crude determinism of vulgar Marxists to acknowledge the uncomfortable truths embedded in the critique. The tendency of accumulation reveals itself in modern plutocracies where wealth consolidates, social mobility ossifies, and the gulf between the Davos class and the wage-earner yawns wider than ever.

To paraphrase Marx (or the Devil), the greatest trick capital ever pulled was convincing the world it was immortal. But here, one must also summon the Hitchensesque suspicion of orthodoxy. Marx’s analytical scalpel is sharp, but his eschatology falters. The proletarian revolution he so confidently forecast has remained an elusive chimera. Capitalism, through reform, adaptation, and a dazzling capacity to reinvent itself (from Keynesianism to neoliberalism, from Fordist factories to digital platforms), has proven to be more Protean than Marx predicted.

So, while the tendency of capitalist accumulation, with all its Darwinian horrors, is perhaps undeniable, its teleology—the inevitable collapse and socialist utopia—remains unfulfilled. The bourgeoisie, rather than digging its own grave, has proven adept at hiring gardeners to landscape it into a golf course.

In short, Marx was right about the sickness but wrong about the patient’s expiry date. Capitalism stumbles, bleeds, and mutates, but still, it marches on. Whether we see this as a triumph of human ingenuity or the prolongation of systemic exploitation depends, I suppose, on which side of the barricade one stands.

Leave a comment