Book Review

Fromm, Erich. The Art of Loving. Thorsons, 1995.

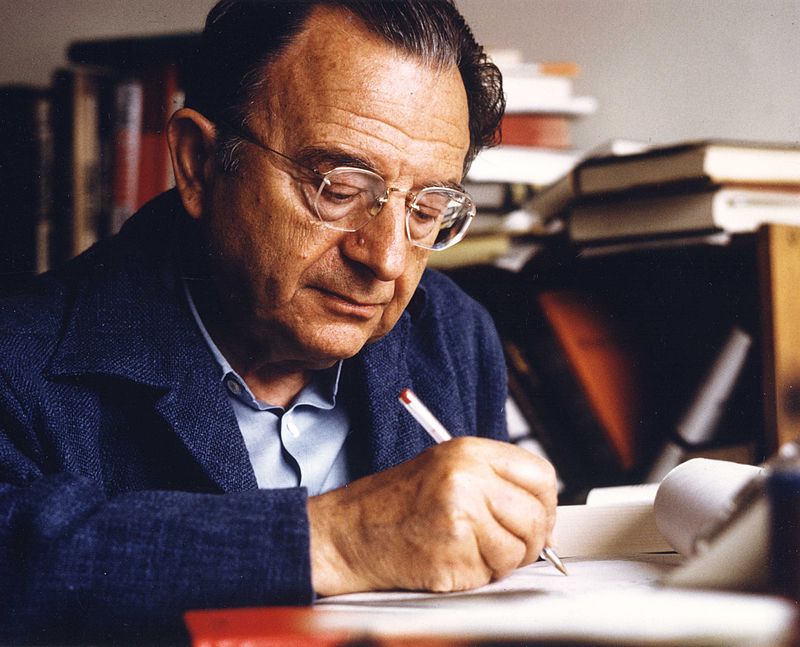

Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving (1956) is a compact but ambitious treatise that reframes love not as a private sentiment or a passively received “falling,” but as an art—an acquired human capacity requiring knowledge, discipline, and practice. Written at the crossroads of psychoanalysis, social theory, and ethical humanism, the book compresses key themes developed more expansively in Escape from Freedom (1941), Man for Himself (1947), and The Sane Society (1955): alienation in modern capitalist societies, the “marketing orientation” of personality, and the possibility of a sane, loving character rooted in productive activity and relatedness. In doing so, Fromm offers a meta-psychology of love that remains strikingly contemporary, even as some of its theological and gendered assumptions now invite critique.

Fromm’s central move is definitional. He dislocates love from an object-centered conception (“finding the right person”) to a faculty-centered one (“becoming a loving person”). Love is not primarily an emotion that happens to us, but a capacity we cultivate through “care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge”—the four elements that, in Fromm’s view, structure all authentic loving relations. These elements function both diagnostically and normatively. They allow Fromm to distinguish productive from symbiotic relations (masochistic or sadistic fusions), to identify narcissism and idolatry as pathologies of relatedness, and to frame love as an ethical practice that presupposes autonomy rather than dependency. In this sense, The Art of Loving is less a manual than a moral anthropology: it describes the conditions under which the human need for union can be met without surrendering individuality.

The famous typology—brotherly love, motherly love, erotic love, self-love, and love of God—works as a set of lenses on the same faculty rather than as mutually exclusive categories. Brotherly love emphasizes solidarity and universalism; motherly love models unconditional affirmation; erotic love risks exclusivity and possessiveness; self-love rejects the false alternative between altruism and “selfishness” by insisting that respect for one’s own integrity and flourishing is a prerequisite for respecting others; and love of God articulates the human orientation toward ultimacy, which, for Fromm, can be conceived theistically or as an ideal of humanistic devotion. What unifies the typology is not sentiment but activity: loving is a doing, a disciplined praxis that resembles artistic mastery more than emotional luck.

Fromm’s most enduring—and prescient—diagnosis is socio-economic. He argues that advanced capitalism produces a “marketing character,” in which persons come to experience themselves and others as commodities to be packaged, exchanged, and appraised. In such a milieu, romantic love tends to be imagined as a marketplace transaction: two “packages” matching attractive features, with intimacy reduced to mutual consumption. Against this, Fromm proposes love as production: an act that generates value through attention, skill, patience, and constancy. This critique travels easily to contemporary forms of mediated intimacy (dating apps, influencer culture, algorithmic curation), where self-presentation and choice architecture intensify the commodification of desire. The book’s call for discipline—so often caricatured as dour—reads, in this light, as a defense of sustained, non-instrumental attention in an economy of distraction.

The psychoanalytic backbone of the text is both a strength and a limit. On the one hand, Fromm’s synthesis of object-relations insights and existential humanism allows him to treat love as a developmental achievement conditioned by early attachments yet transformable through practice and social reform. His analyses of narcissism, symbiosis, and the fear of freedom retain clinical bite. On the other hand, some formulations are thinly theorized by contemporary standards (e.g., the inevitability of certain gendered roles in mother/child relations) and tend to universalize mid-century, heteronormative family expectations. While Fromm often gestures toward egalitarian relations, his erotics remain largely organized around binary gender scripts and monogamous pair-bonding, with limited attention to queer, polyamorous, or non-dyadic forms of love that have since entered both clinical and sociological literatures.

Fromm’s theological register—especially the discussion of love of God—will divide readers. For some, it supplies a symbolic vocabulary for orienting the loving subject toward ideals of justice and compassion beyond immediate reciprocity; for others, it risks abstracting love from the material conditions that enable or suppress it. Yet even here, the text’s humanistic core is clear: “God” often functions as a cipher for the highest human potentials rather than a confessional claim, and Fromm explicitly offers a secular equivalence.

Philosophically, The Art of Loving advances an ethics of virtue and practice rather than commandment. Its normative ideal is the “productive character,” whose energies are expressed in creative work and relatedness rather than in having, consuming, or dominating. This links the book to Fromm’s later To Have or To Be?, where he contrasts acquisitive and being-modes of existence. As an ethical program, this remains compelling: it binds intimate life to broader questions of social organization, suggesting that a society that trains citizens in commodification will predictably fail at love. The implication—radical for a “self-help classic”—is that personal transformation and social transformation are inseparable.

Still, there are lacunae. The book offers little in the way of concrete sociological mechanisms for scaling loving praxis beyond the family and small group, and its political economy, while suggestive, remains programmatic. Moreover, its emphasis on discipline and mastery, though corrective to sentimentalism, can underplay contingency, trauma, and the asymmetries of power that shape who can practice love, at what cost, and with what risks. Contemporary feminist, queer, and decolonial critiques would press these points: how do race, class, gender, and imperial histories structure the very possibilities of “care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge”?

Notwithstanding these limitations, The Art of Loving endures because it refuses the false dichotomy between intimate life and social critique. It offers a vocabulary for evaluating relationships ethically without moralism, and it insists that love is not a miracle but a discipline—one that can be learned. As a concise statement of psychoanalytic humanism, it remains a generative text for clinicians, social theorists, and anyone seeking to link the micro-politics of the heart to the macro-structures of society.

Leave a comment