Book Review

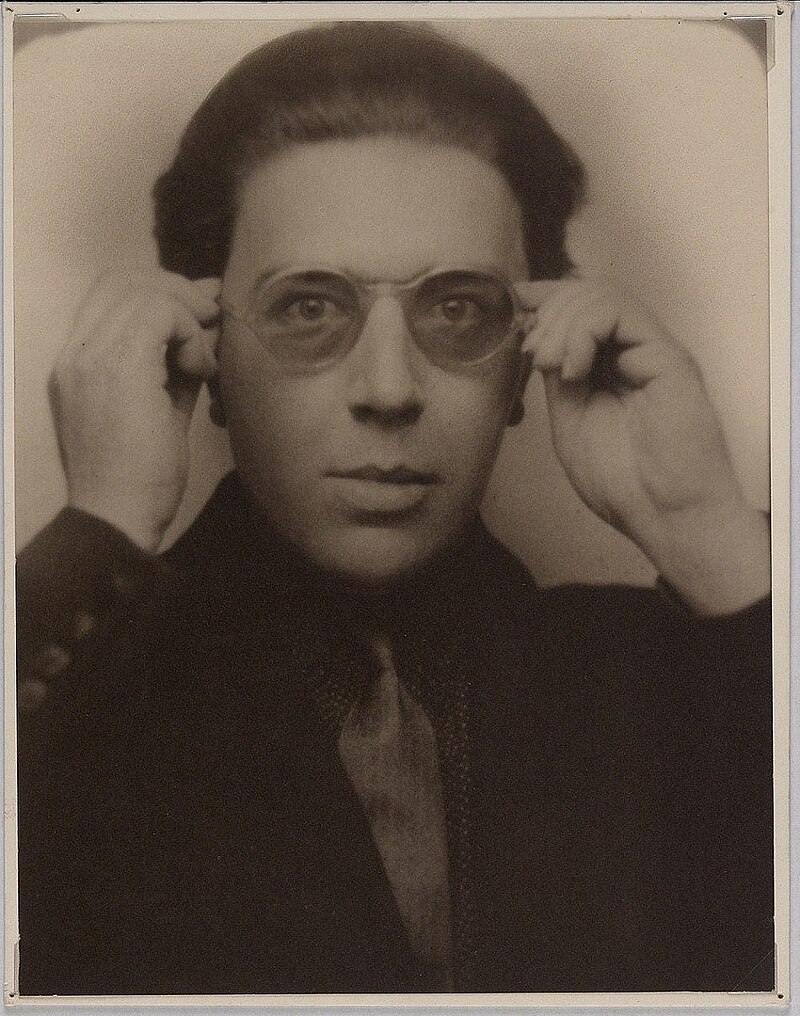

Breton, André. Nadja. Translated by Mark Polizzotti, Verso, 1999.

Introduction

André Breton’s Nadja (1928), a foundational Surrealist text, continues to resist neat categorization. Half novel, half memoir, it dramatizes the fleeting encounters between Breton and the enigmatic figure of Nadja, who becomes muse, mirror, and ultimately, casualty of bourgeois rationalism. Mark Polizzotti’s translation captures the cadences of Breton’s obsessive prose and its disorienting blend of documentary precision and dreamlike digression. From a Marxist perspective, Nadja is a paradoxical work: at once a rebellion against capitalist rationality through Surrealist experiment, and a symptom of the very alienation it seeks to transcend.

Surrealism and Commodity Fetishism

Breton situates Nadja against the cold backdrop of Paris, a city transformed by commodity culture into a labyrinth of arcades, boulevards, and cafes. His flânerie, though romanticized, is inescapably bound to the circulation of capital: shop windows, theaters, hotels, and bookstalls all haunt the text. Nadja herself, fleeting and spectral, is figured in terms that evoke Marx’s notion of commodity fetishism—she is both subject and object, invested with mystical qualities while effaced as a woman. Her madness, institutionalization, and disappearance point to the structural violence of bourgeois society, which commodifies desire yet pathologizes and discards those who do not conform to its logics.

Alienation and the Role of the Artist

Breton positions the Surrealist artist as revolutionary seer, capable of revealing the dialectic between dream and reality. Yet Nadja simultaneously illustrates the limits of this avant-garde politics. Breton’s Parisian dérive remains confined to the intellectual bohemia of cafés and galleries, worlds still tethered to bourgeois patronage. His relationship with Nadja exposes the contradictions of Surrealist praxis: while she embodies liberation from rationalized alienation, she is also marginalized and ultimately silenced. From a Marxist standpoint, this tension demonstrates the difficulty of locating revolutionary potential within aesthetic experimentation absent concrete social struggle.

Translation and Mediation

Polizzotti’s translation succeeds in transmitting Breton’s obsessive rhythms, abrupt shifts, and idiosyncratic phrasing, while also maintaining fidelity to the historical Surrealist project. His critical apparatus provides context without deflating the text’s disorienting effects, crucial for contemporary readers who might otherwise read Nadja as merely a love story. This mediation reinforces how translation itself is a form of cultural production shaped by late-capitalist publishing markets. Breton’s Surrealist “marvelous” arrives refracted through the global circuits of academic consumption—a reminder of the continuing commodification of avant-garde rebellion.

Conclusion

Nadja remains indispensable for understanding Surrealism’s attempt to puncture capitalist rationality with the disruptive power of desire and the unconscious. Yet from a Marxist vantage point, its failures are as revealing as its triumphs. Breton’s mystification of Nadja underscores the gendered and class contradictions embedded in the Surrealist project: women serve as vessels for male artistic liberation while bearing the brunt of capitalist and patriarchal repression. The work thus stages, almost in spite of itself, the unresolved contradiction between artistic revolt and material transformation. Polizzotti’s translation ensures that this tension resonates powerfully for contemporary readers, making Nadja a text that is both alluring and troubling in equal measure.

Final Judgment

A brilliant but flawed Surrealist text whose revolutionary promise is circumscribed by its own entanglement with bourgeois culture. Essential reading for Marxist critics interested in the dialectics of art, alienation, and the commodification of desire.

Leave a comment