My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

Introduction

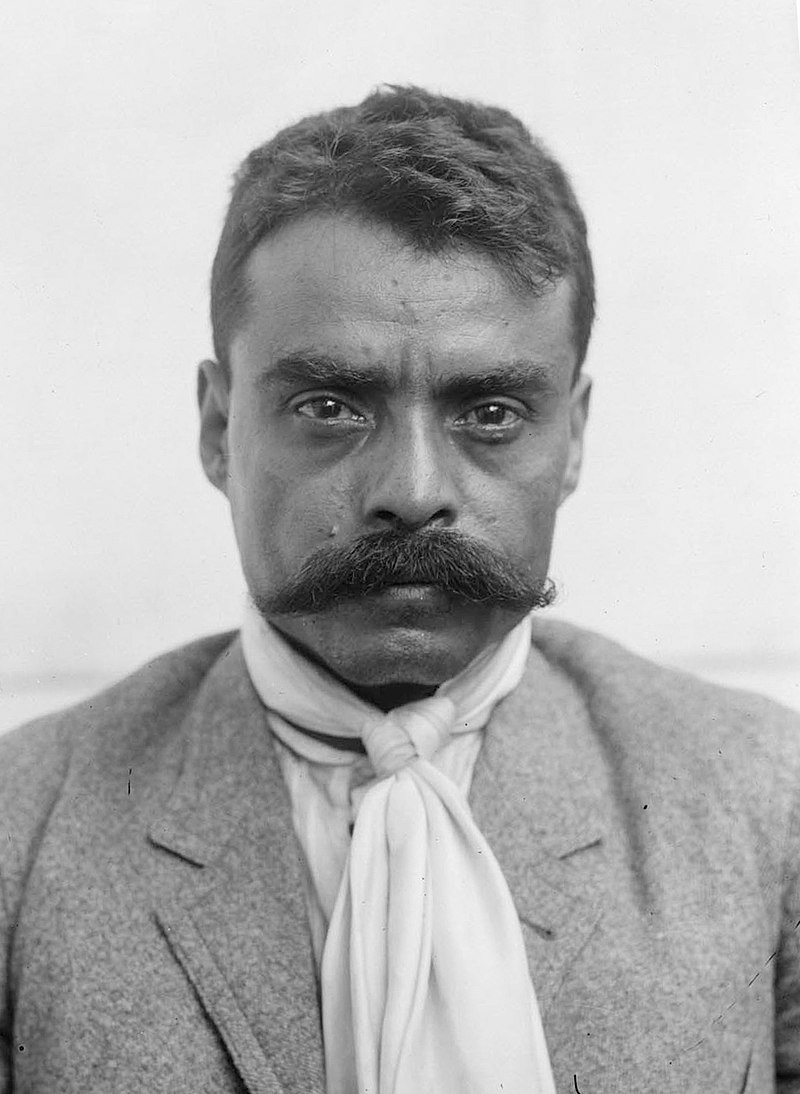

Emiliano Zapata Salazar (1879–1919) stands as one of the most enduring symbols of agrarian revolution and peasant struggle in Latin American history. His leadership during the Mexican Revolution not only shaped the trajectory of the revolution itself but also left a profound legacy on land reform, rural mobilization, and revolutionary ideology in the twentieth century. Zapata’s uncompromising vision of social justice and “Tierra y Libertad” (“Land and Liberty”) made him an icon of popular resistance, deeply influencing subsequent generations of peasants, socialists, and revolutionaries worldwide.

Early Life and Social Context

Emiliano Zapata was born on August 8, 1879, in Anenecuilco, Morelos, a rural village south of Mexico City. He was the ninth of ten children in a family of campesinos (peasants), whose status as smallholders was steadily eroded by the liberal reforms and “modernization” policies of the Porfirio Díaz regime. The concentration of land into vast haciendas—controlled by a handful of wealthy elites and foreign investors—dispossessed countless indigenous and mestizo communities in Morelos and across Mexico.

Zapata’s early life was marked by this social transformation. His family maintained a small parcel of land, but growing up, Zapata witnessed the forced expropriation of communal lands, the degradation of peasant rights, and the rise of rural indebtedness and coercive labor practices. This context would shape his entire political consciousness and militant commitment to land reform.

Political Awakening and Early Leadership

By his early twenties, Zapata had become deeply involved in local efforts to reclaim village lands. In 1909, at age 30, he was elected president of the village council of Anenecuilco, a rare honor reflecting his reputation for integrity and leadership. Zapata spearheaded petitions to local authorities and courts, demanding restitution of expropriated lands. When legal avenues proved futile—due to pervasive corruption and the alliance of state power with hacienda owners—he increasingly turned to direct action.

Zapata’s activism coincided with the broader political ferment that erupted into the Mexican Revolution in 1910. The initial insurrection, led by Francisco I. Madero against the Díaz dictatorship, attracted widespread support from peasants eager for change. Zapata, however, quickly became disillusioned with Madero’s reluctance to confront the land question.

The Plan de Ayala and Revolutionary Struggle

In November 1911, following Madero’s accession to power and his failure to address agrarian demands, Zapata and his followers issued the Plan de Ayala—a foundational manifesto of the Zapatista movement. The Plan denounced Madero’s betrayal and articulated a radical program: immediate restitution of village lands, expropriation of one-third of all hacienda land for redistribution, and the defense of rural communities by armed peasant forces. Its rallying cry—“Tierra y Libertad”—became synonymous with the Zapatista cause.

The Zapatista movement, centered in the southern states of Morelos, Puebla, and Guerrero, rapidly evolved from a local uprising to a formidable rural insurgency. Zapata demonstrated exceptional skill as a guerrilla leader, organizing decentralized bands of fighters and maintaining popular support among the peasantry through strict discipline and an unwavering commitment to local autonomy. Unlike many revolutionary leaders, Zapata refused national political office, insisting that the revolution remain rooted in grassroots demands and peasant agency.

Relationship with Other Revolutionary Factions

Zapata’s relationship with other revolutionary factions was complex and often antagonistic. While temporarily allied with northern leaders such as Pancho Villa and the Constitutionalists, his uncompromising insistence on land reform and local autonomy set him at odds with more moderate or centralizing forces. Zapata’s interactions with Venustiano Carranza, leader of the Constitutionalists, were especially fraught; Carranza viewed Zapata as a threat to national authority, while Zapata denounced Carranza’s constitutional reforms as inadequate and treacherous.

Despite numerous attempts at negotiation, the Zapatista movement found itself increasingly isolated after 1916, as the revolutionary government consolidated power. The ensuing military campaigns devastated Morelos, but Zapata’s forces continued a stubborn guerrilla resistance.

Assassination and Legacy

On April 10, 1919, Zapata was assassinated in Chinameca, Morelos, in a government-engineered ambush orchestrated by Colonel Jesús Guajardo under Carranza’s orders. Zapata’s death marked the end of the organized Zapatista army, but not the end of his influence. Within a decade, the Mexican government—facing continued rural unrest and the threat of renewed insurrection—implemented significant land reforms, some inspired by Zapatista demands.

Zapata’s legacy endures as a symbol of radical agrarianism, indigenous rights, and the principle of popular sovereignty. His image and slogans have inspired countless social movements, from the 1930s Cárdenas reforms to the neo-Zapatista uprising in Chiapas in 1994. Zapata’s emphasis on grassroots democracy and his suspicion of centralized authority remain central reference points in debates on land, autonomy, and revolution in Mexico and beyond.

Historical Significance

Emiliano Zapata occupies a unique position in the pantheon of revolutionary leaders. Unlike figures who sought to seize or maintain state power, Zapata embodied a vision of revolution as a process of popular self-emancipation—a struggle waged from below and sustained by the everyday actions of ordinary people. His life and martyrdom stand as a testament to the enduring power of the peasantry in shaping modern history.

Selected Bibliography

• Brunk, Samuel. Emiliano Zapata: Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

• González y González, Emma. Zapata: The Ideology of a Peasant Revolutionary. Cengage Learning, 2015.

• Womack, John Jr. Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. Vintage Books, 1970.

• Katz, Friedrich. The Life and Times of Pancho Villa. Stanford University Press, 1998. (Includes comparative analysis with Zapata)

• Hart, John Mason. Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution. University of California Press, 1997.

• Salas, Elizabeth. Soldaderas in the Mexican Military: Myth and History. University of Texas Press, 1990.

• Gilly, Adolfo. The Mexican Revolution. Verso, 2005.

• Zapata, Emiliano. The Plan de Ayala and Other Documents. (Collected translations; available in various editions).

Leave a comment