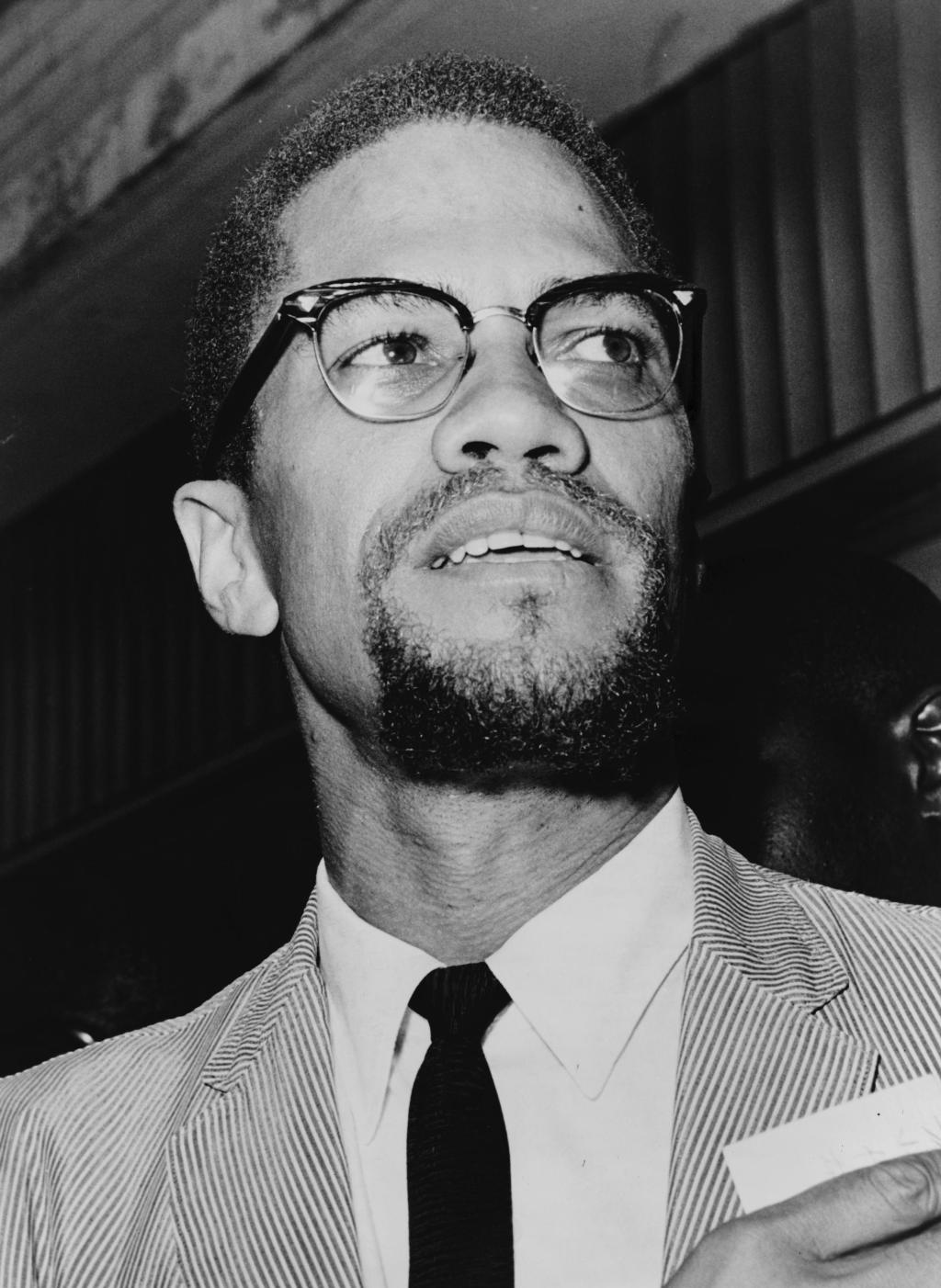

My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

Early Life and Formative Years

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925. His father, Earl Little, was a Baptist minister and a committed follower of Marcus Garvey, whose ideas about Black nationalism profoundly influenced Malcolm’s early exposure to radical Black thought. Earl’s violent death in 1931, likely at the hands of white supremacists, and the institutionalization of his mother Louise Little, led to a fractious and unstable upbringing. These early experiences shaped Malcolm’s acute understanding of systemic racism and the fragility of Black family life under white supremacy.

Malcolm drifted into petty crime during his youth, eventually being incarcerated in 1946. It was during his six-year prison term that he experienced an intellectual awakening, immersing himself in history, philosophy, and religion. He converted to the Nation of Islam (NOI), a Black nationalist religious movement led by Elijah Muhammad, and adopted the name Malcolm X to reject his “slave name.”

Nation of Islam and Rise to Prominence (1952–1964)

Upon release from prison in 1952, Malcolm X became one of the Nation of Islam’s most dynamic and visible ministers. His electrifying oratory, intellectual rigor, and uncompromising critique of white supremacy and integrationist liberalism distinguished him within the Black liberation movement. He was appointed minister of several mosques and served as the national spokesman for the NOI.

Malcolm’s message was characterized by a militant critique of American racism, condemnation of the civil rights establishment’s emphasis on nonviolence, and advocacy for Black self-defense, economic independence, and cultural pride. His popularity grew rapidly, particularly among urban Black youth disillusioned with the slow pace and conservative orientation of the mainstream civil rights movement.

However, growing tensions between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad—stemming from ideological disagreements and revelations of Elijah’s moral failings—led to a dramatic break in March 1964. Malcolm’s departure marked a critical transformation in his political and spiritual trajectory.

Later Years: Internationalism and Revolutionary Turn (1964–1965)

After leaving the Nation of Islam, Malcolm founded Muslim Mosque, Inc. and the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). Inspired by the anti-colonial struggles in Africa and Asia, Malcolm began advocating a more explicitly revolutionary and internationalist vision. His journey to Mecca in April 1964 profoundly affected his understanding of Islam and race; upon adopting Sunni Islam, he took the name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. He returned with a more global analysis of oppression, calling for human rights rather than just civil rights and connecting the Black freedom struggle in the U.S. to broader anti-imperialist movements.

His speeches during this final year emphasized class struggle, solidarity among oppressed peoples, and the need for structural transformation of capitalist society. Malcolm increasingly spoke of socialism as a necessary framework to combat racial and economic exploitation.

Assassination and Legacy

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated while preparing to deliver a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. Three men associated with the Nation of Islam were convicted of the murder, though the full circumstances remain debated.

Malcolm X’s intellectual legacy and revolutionary vision have grown considerably in the decades since his death. He is now widely regarded as a foundational figure in Black radical thought and an icon of anti-imperialist resistance. His life trajectory—from street hustler to revolutionary internationalist—epitomizes the capacity for political transformation rooted in historical consciousness and self-education.

Intellectual Contributions

Malcolm X was not a theorist in the academic sense, but his speeches and writings reveal a powerful and evolving political philosophy. His emphasis on self-determination, international solidarity, and structural analysis of racism laid the groundwork for later movements such as the Black Panther Party and global anti-colonial struggles. His critiques of capitalism, U.S. imperialism, and white liberalism remain deeply relevant to contemporary debates in critical race theory and postcolonial studies.

Select Works

• The Autobiography of Malcolm X (as told to Alex Haley, 1965) – A seminal text in African American literature and political autobiography.

• Malcolm X Speaks (ed. George Breitman, 1965) – A collection of key speeches from his final year, revealing his turn toward revolutionary humanism.

• The End of White World Supremacy (ed. Imam Benjamin Karim, 1971) – Transcripts of speeches in which Malcolm critiques white power and imperialism.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

• Malcolm X and Alex Haley. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Grove Press, 1965.

• Malcolm X. Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements. Ed. George Breitman. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1965.

• Malcolm X. By Any Means Necessary. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970.

Secondary Sources

• Marable, Manning. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. New York: Viking, 2011.

• Perry, Bruce. Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America. Barrytown: Station Hill, 1991.

• Carson, Clayborne. Malcolm X: The FBI File. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1991.

• Dyson, Michael Eric. Making Malcolm: The Myth and Meaning of Malcolm X. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

• Sales, William W. From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Boston: South End Press, 1994.

• DeCaro, Louis A. On the Side of My People: A Religious Life of Malcolm X. New York: NYU Press, 1996.

Leave a comment