The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), often affectionately and defiantly known as the “Wobblies,” represents one of the most remarkable chapters in the history of the American labor movement. Founded in Chicago in June 1905, this eclectic, rebellious, and fiercely egalitarian labor union arose in direct opposition to the perceived moderation, compromise, and conservatism of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). To understand the Wobblies is to grasp the radicalism of early 20th-century America—a period marked by violent class conflict, fervent idealism, and the burgeoning discontent of laborers facing grinding exploitation.

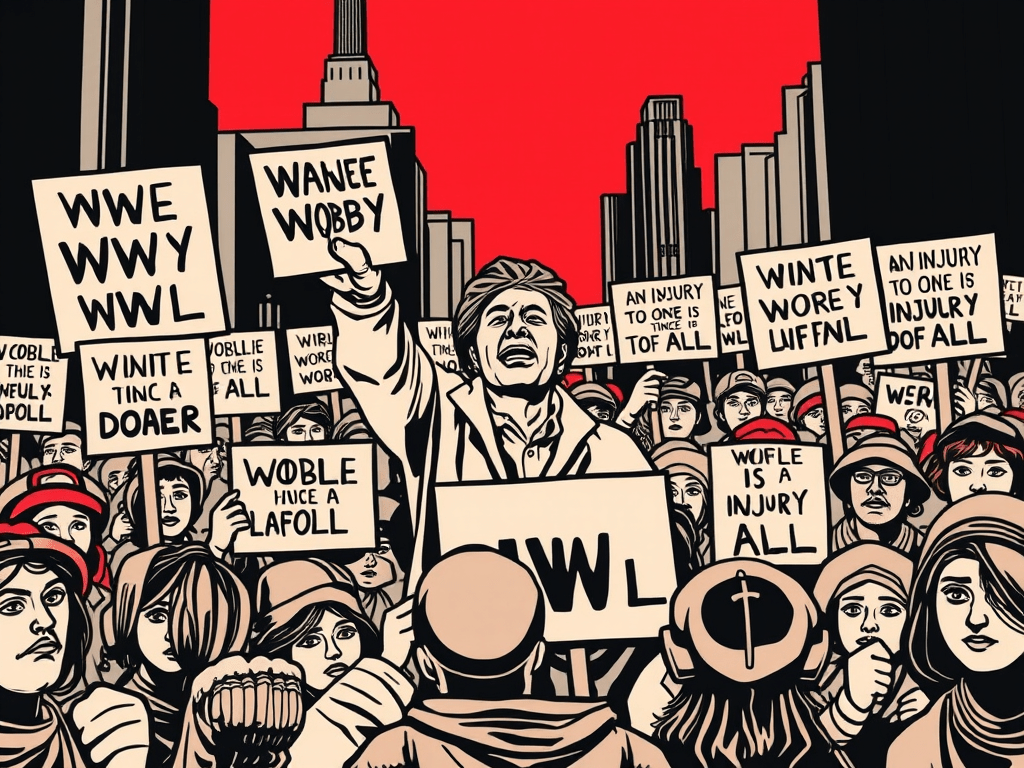

At its ideological heart, the IWW espoused the principles of revolutionary syndicalism, blending Marxist class analysis with a distinctly American sense of individualism and rebellion. Unlike the AFL, which focused on skilled craft unions, the IWW sought to organize all workers regardless of race, gender, or skill level into “One Big Union.” Its legendary slogan, “an injury to one is an injury to all,” encapsulated its spirit of solidarity and uncompromising struggle.

From its inception, the IWW proved itself profoundly audacious. Its founding convention attracted figures as diverse as William “Big Bill” Haywood, Eugene V. Debs, Lucy Parsons, and Mother Jones. These were not mere bureaucrats or timid reformers; they were revolutionaries who refused to accept incremental improvements as sufficient compensation for fundamental injustices. The Wobblies sought nothing less than the total abolition of the capitalist system, which they identified as the root cause of workers’ suffering.

The heyday of the IWW coincided with explosive labor struggles across the United States. Notably, the union led major strikes, including the Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912—famously known as the “Bread and Roses” strike—which dramatically improved wages and conditions for workers. Another pivotal moment was the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike, which, despite ultimately faltering, showcased the union’s ability to mobilize mass actions and attract national attention.

What distinguished the Wobblies, beyond their revolutionary zeal, was their extraordinary cultural impact. They understood intuitively that culture was a weapon in the struggle for justice. Joe Hill, arguably the most famous Wobbly martyr, captured this perfectly through his songwriting. Hill’s satirical and incisive lyrics, from “The Preacher and the Slave” to “There Is Power in a Union,” became anthems of working-class resistance, galvanizing workers far beyond the IWW’s own ranks.

Yet, the IWW’s boldness drew fierce repression from government and business interests. World War I provided the perfect pretext for a systematic crackdown against the union, branding its members as subversives, traitors, and saboteurs. The infamous Espionage Act of 1917, augmented by state and local authorities’ relentless persecution, decimated the IWW’s leadership. Many Wobblies faced imprisonment, deportation, or worse—like Joe Hill, execution on dubious charges.

Despite such persecution, the Wobblies’ legacy endures. Their vision of an inclusive, fighting unionism deeply influenced subsequent labor movements and inspired generations of radicals, from civil rights activists to anti-war campaigners. Today, in an era of renewed labor unrest and stark economic inequality reminiscent of the early 20th century, the history of the IWW offers both a cautionary tale and a reservoir of inspiration. It reminds us that meaningful social change has rarely come from polite appeals to power but rather from the courage, solidarity, and sheer audacity epitomized by the defiant spirit of the Wobblies.

Leave a comment