My Socialist Hall of Fame

During this chaotic era of vile rhetoric and manipulative tactics from our so-called bourgeois leaders, I am invigorated by the opportunity to reflect on Socialists, Revolutionaries, Philosophers, Guerrilla Leaders, Partisans, and Critical Theory titans, champions, and martyrs who paved the way for us—my own audacious “Socialism’s Hall of Fame.” These are my heroes and fore-bearers. Not all are perfect, or even fully admirable, but all contributed in some way to our future–either as icons to emulate, or as warnings to avoid in the future.

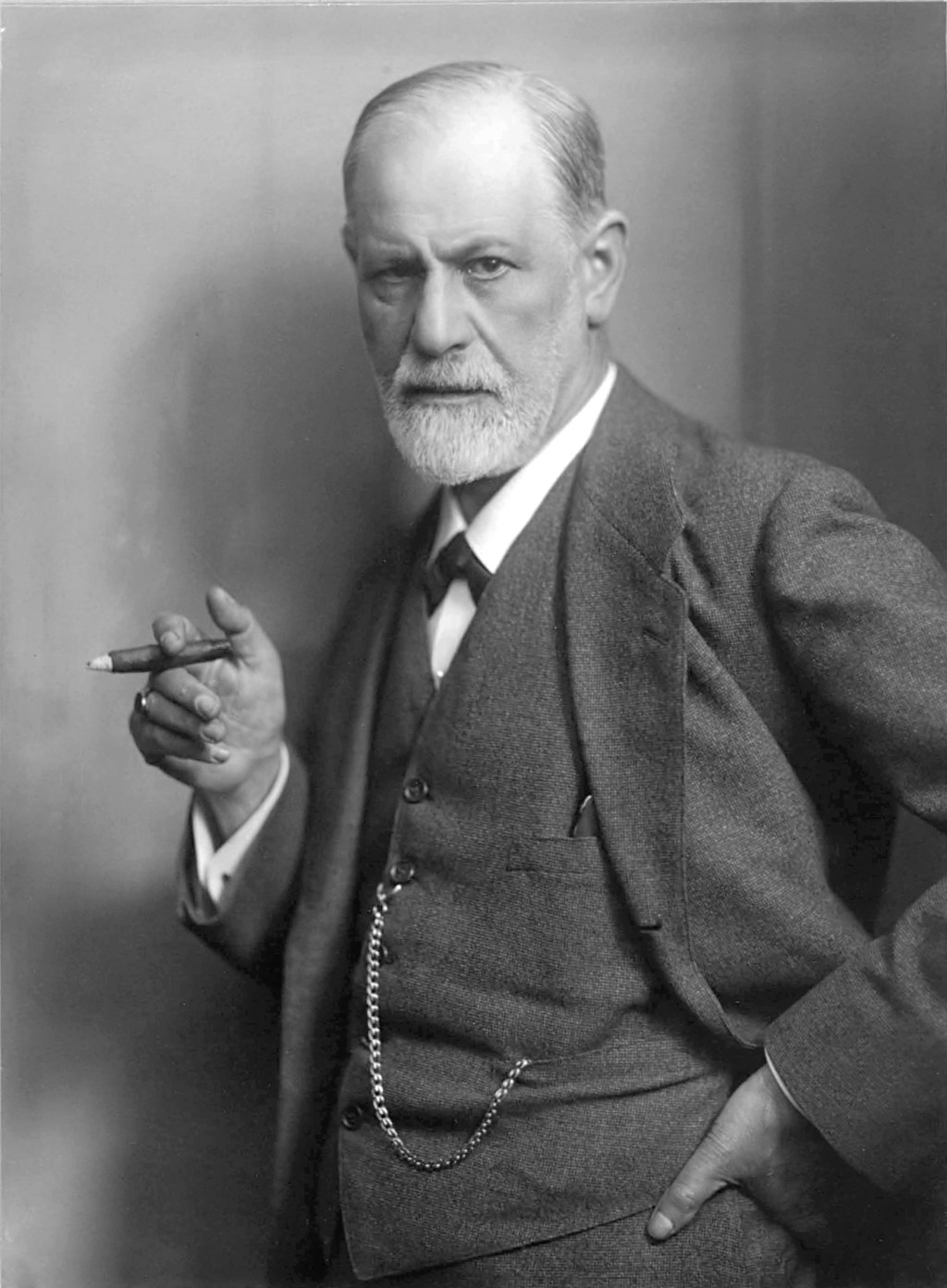

Though Freud was not a socialist, his impact on 20th Century philosophy and critical theory was unmistakable, as he profoundly influenced various disciplines, including psychology, literature, and cultural studies. His exploration of the unconscious mind challenged conventional beliefs and opened new avenues for understanding human behavior. Additionally, Freud’s work on the dynamics of repression, desire, and identity has left an indelible mark on critical theorists who examine the intersections of power, culture, and individual subjectivity. These contributions prompted scholars to rethink traditional narratives and embrace a more nuanced perspective on societal structures and human motivations.

Sigmund Freud (May 6, 1856 – September 23, 1939) was an influential Austrian neurologist best known as the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychological disorders through dialogue between patient and analyst. Freud profoundly shaped the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy.

Born in Freiberg, Moravia (now the Czech Republic), Freud moved to Vienna, Austria, with his family at age four. He studied medicine at the University of Vienna, graduating in 1881, and began his medical career with research in neurology. Freud’s exposure to the practice of hypnosis by Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris significantly impacted his understanding of hysteria and other neurotic conditions.

In the 1890s, Freud developed groundbreaking theories concerning the unconscious mind, introducing fundamental concepts such as repression, the Oedipus complex, dream interpretation, and psychosexual development. His influential works include “The Interpretation of Dreams” (1900), where he proposed that dreams reveal unconscious desires, and “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality” (1905), detailing his controversial views on human sexuality.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory emphasized the significance of early childhood experiences, unconscious drives, and internal conflicts in shaping human behavior and personality. Throughout his life, Freud continued to refine and expand his theories, producing influential writings such as “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” (1920) and “Civilization and Its Discontents” (1930).

Facing persecution from the Nazi regime, Freud fled Vienna in 1938 and relocated to London, where he continued his work until his death in 1939 from complications related to cancer of the jaw.

Bibliography:

Works by Freud:

• Freud, Sigmund. “The Interpretation of Dreams.” (1900).

• Freud, Sigmund. “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.” (1905).

• Freud, Sigmund. “Totem and Taboo.” (1913).

• Freud, Sigmund. “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.” (1920).

• Freud, Sigmund. “The Ego and the Id.” (1923).

• Freud, Sigmund. “Civilization and Its Discontents.” (1930).

• Freud, Sigmund. “Moses and Monotheism.” (1939).

Secondary Sources:

• Gay, Peter. “Freud: A Life for Our Time.” W.W. Norton & Company, 1988.

• Jones, Ernest. “The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud.” 3 vols. Basic Books, 1953–1957.

• Rieff, Philip. “Freud: The Mind of the Moralist.” University of Chicago Press, 1959.

• Sulloway, Frank J. “Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend.” Harvard University Press, 1992.

Freud’s ideas remain influential despite ongoing debate, significantly impacting psychology, literature, cultural studies, and beyond.

Leave a comment