An ongoing series of reflections on Marxist economics after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

One of the many perennial virtues of Marxist thought—whether one agrees with its prescriptions or not—is its remarkable ability to cut through bourgeois sentimentalism and name things for what they are. Karl Marx dared to ask questions that still gnaw at the entrails of modern capitalism: what is labor, and what distinguishes labor that generates wealth from labor that merely shuffles it around? This distinction between “productive” and “unproductive” labor, as set out in Marxist economic theory, is not only analytically useful but morally clarifying.

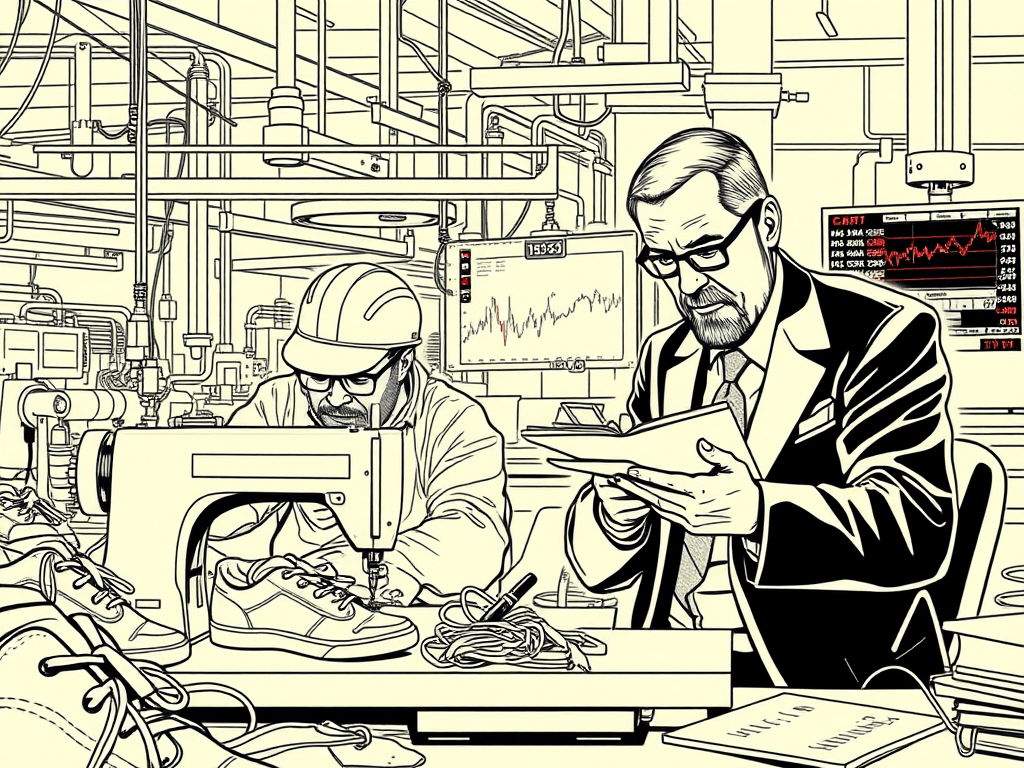

Marxist economists, with their unblinking gaze fixed on the gears and levers of the capitalist mode of production, define productive labor as that which creates surplus value. In layman’s terms, productive labor is labor that directly expands capital. It is not simply work that is “hard” or “skilled” or “noble”—those are the pastel brushstrokes of liberal idealism—but labor which results in the generation of profit for the capitalist. The factory worker stitching together sneakers for pennies an hour is productive, in the Marxist sense, because her sweat materializes as surplus value in the coffers of the corporation. The stockbroker, on the other hand, may receive an obscene bonus for executing speculative trades, but his work does not produce new value; it merely redistributes existing wealth—hence, “unproductive” labor.

To modern ears, numbed by decades of neoliberal propaganda, this classification may sound harsh or reductive. After all, does not all labor have dignity? Certainly, every human being deserves dignity, but labor itself, in Marxist terms, is not dignified by its social status or emotional resonance but by its relationship to capital. If one is engaged in labor that produces commodities—goods or services that are then sold for more than the wage paid to the laborer—one is engaged in productive labor under capitalism.

But there is a peculiar irony that a Marxist is keen to savor. The janitor, wiping down the offices of a gleaming high-rise, is unproductive labor. Not because his work lacks merit, but because it does not produce surplus value directly—it services the conditions under which productive labor occurs. Yet within the Marxist framework, such roles are indispensable, albeit parasitic on the primary act of value creation. Without the janitor, the factory worker or office drone may toil less efficiently; yet the janitor’s labor is still labeled “unproductive” from the vantage of capital.

It is here that Marxist theory reveals both its moral force and its analytic ruthlessness. Marx, and his intellectual heirs, were not moralizing about who “deserves” their wage, nor romanticizing the “working class” in the vulgar, populist sense. Rather, they offered an X-ray of capitalism itself, exposing how its organs and arteries funnel value from the worker to the owner. To understand the distinction between productive and unproductive labor is to understand the anatomy of exploitation.

Yet there is something refreshingly honest—almost perversely optimistic—in this brutal taxonomy. For it suggests that labor is not inherently servile; it is the conditions under which labor is sold and appropriated that rob it of its humanity. Marxists, unlike some modern “self-help” grifters and TED Talk evangelists, do not tell you to “love what you do.” They tell you to understand what you do in relation to power and capital.

The late Marx himself, with that leonine beard and volcanic intellect, would likely scoff at the corporate wellness seminars and hollow promises of “leaning in.” But he might also permit a wry smile at the recognition that millions of workers today still inhabit the very structure he dissected over 150 years ago. The productive/unproductive dichotomy remains a scalpel that cuts to the bone of labor’s true condition under capitalism.

And while many of us may recoil from the bleakness of this diagnosis, we might also take solace in the clarity it offers. For in knowing where one stands—whether as a producer of surplus value or a functionary within its orbit—there is a kind of liberation. It is the first step toward reclaiming labor’s humanity from the relentless logic of capital.

Thus, Marxist economists offer not just an economic theory, but a revelatory lens. And in this dark glass, if one peers long enough, there is the faint glimmer of hope: the hope that once we understand the mechanics of exploitation, we might yet dare to unmake them.

Leave a comment