An ongoing series of reflections of my thoughts on historical materialism after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

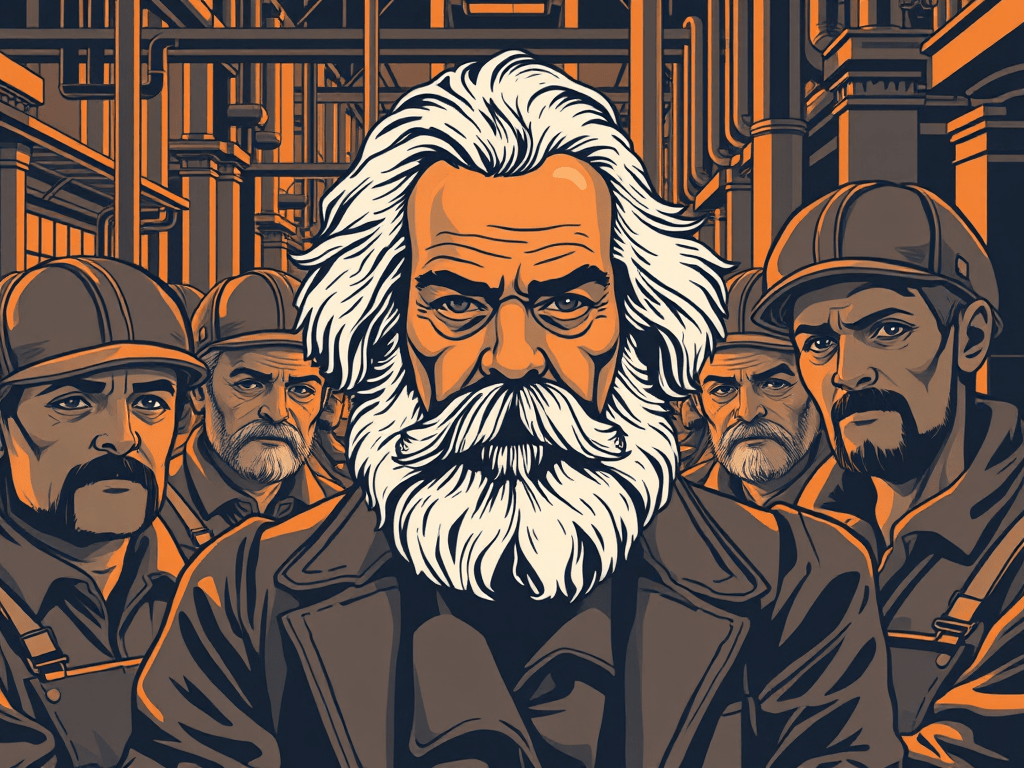

Karl Marx, never one to mince words or soften the radicalism of his analysis, described the working class as the “gravediggers” of capitalism. This evocative metaphor, drawn from The Communist Manifesto (1848), captures the paradox of capitalism’s self-destructive tendencies: the very system that thrives on the exploitation of labor unwittingly creates the conditions for its own demise. Like much of Marx’s writing, this insight is both piercing and unsettlingly prophetic. The working class, forged in the crucible of industrial society, is not merely a passive victim but an active agent of historical change, poised to bury the exploitative system that created it.

Capitalism’s Internal Contradictions

To understand why Marx bestowed this morbid honorific upon the proletariat, we must first examine his analysis of capitalism’s inherent contradictions. Marx believed that capitalism, by its very nature, is a system that generates wealth and inequality in equal measure. In Das Kapital, he describes the central mechanism of exploitation: “Capital is dead labor, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.” This system’s insatiable appetite for profit drives it to expand, innovate, and exploit ever more ruthlessly. Yet in doing so, it also creates its own nemesis.

The proletariat—Marx’s term for the working class—is both a product and a victim of this process. Capitalism assembles workers into factories, urban centers, and industries, concentrating them and stripping them of individual autonomy. What emerges is not just a mass of laborers but a collective force, bound by shared exploitation and increasingly aware of its power. As Marx and Engels put it in The Communist Manifesto: “What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.”

The Role of Class Consciousness

Marx’s theory hinges on the idea of class consciousness—the realization among workers that they share a common enemy and a collective interest. This is not a given; it must be forged through struggle and experience. In the early stages of industrial capitalism, workers are fragmented and isolated, competing against one another for survival. But as capitalism develops, it inadvertently unites them. Factories bring workers together, unions are formed, and strikes become organized acts of defiance. Marx believed that this process would inevitably lead to the proletariat recognizing its historical role as capitalism’s gravedigger.

Critically, Marx did not romanticize the working class or portray them as noble saviors. He was fully aware of their flaws and divisions. Yet he saw in them the potential for revolutionary transformation, born not out of idealism but necessity. In one of his most incisive observations, he writes: “History does nothing, it ‘possesses’ no enormous wealth, it ‘wages’ no battles. It is man, real, living man, who does all that, who possesses and fights; history is not, as it were, a person apart, using man as a means to achieve its own aims; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims.” The working class, then, is not a passive instrument of historical inevitability but an active participant in the struggle to reshape society.

Why the Gravediggers Have Not Yet Dug the Grave

The brilliance of Marx’s analysis lies in its dialectical understanding of capitalism, but the history since The Communist Manifesto was published raises an uncomfortable question: why has the working class not fulfilled its role as capitalism’s gravedigger? Why does the system, despite its crises and contradictions, persist?

The answer lies partly in the adaptability of capitalism. Far from collapsing under the weight of its contradictions, the system has repeatedly reinvented itself. Labor laws, welfare states, and consumer culture have blunted the sharp edges of exploitation, at least in the developed world. Globalization has diffused revolutionary potential by outsourcing production to distant lands, where workers are less organized and more vulnerable.

Moreover, the proletariat itself has been fragmented in new ways. The rise of the gig economy, the decline of unions, and the alienation fostered by digital capitalism have made solidarity more elusive. In this context, the “gravedigger” metaphor may seem quaint, a relic of a bygone industrial era. Yet, as Marx might remind us, appearances can be deceiving. Beneath the surface, the contradictions remain. The recent resurgence of labor activism, from Amazon warehouses to Hollywood picket lines, suggests that the working class is not as dormant as it may appear.

The Moral and Historical Significance

Marx’s vision of the working class as capitalism’s gravediggers is not merely an economic prediction but a profound moral statement. It is a reminder that the system’s victims have the power to become its undoing. In an age of staggering inequality and ecological catastrophe, this insight feels more relevant than ever. Capitalism, for all its resilience, cannot escape its own logic. As Marx put it, “The development of modern industry cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers.”

The question, then, is not whether capitalism’s grave will be dug, but when, and by whom. Will the working class rise to the occasion, or will history take an altogether darker turn? In either case, Marx’s metaphor reminds us that no system, however powerful, is eternal. The gravediggers are always waiting.

Leave a comment