An ongoing series of reflections of my thoughts on historical materialism after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

It was Karl Marx, with his typically scalding wit, who observed that capitalism is the first economic system in history to “burst asunder all fetters.” No longer would traditions or theocratic hierarchies dictate the organization of production and society; instead, the restless, ravenous forces of capital would assume that mantle. Central to this metamorphosis—the engine that powered capitalism’s ascent—was the ceaseless revolutionizing of the means of production. In no other system has the compulsion to innovate, destroy, and rebuild become a defining imperative, and in no other system has this process unleashed such transformative and often catastrophic consequences.

Historical Precedents: Stagnation vs. Innovation

Let us begin by contrasting capitalism’s dynamism with the stasis of its predecessors. Feudal economies, with their agrarian focus and rigid social hierarchies, depended on timeworn methods of production. Innovations, when they occurred, were incremental and often resisted by entrenched powers. A medieval plow was not fundamentally different from its Roman ancestor, just as the serf’s condition remained indistinguishable from that of the slave in antiquity. The pace of change was glacial, not because innovation was impossible, but because it was unnecessary to maintain the established order.

Capitalism, however, is a system addicted to change. Where feudal lords were content to extract rents, capitalists must perpetually reinvest profits to survive. This compulsion finds its clearest expression in technological innovation—the relentless revolutionizing of the means of production. From the spinning jenny to the microchip, every epochal leap forward in capitalism’s development has been fueled by new tools, machines, and methods that increase productivity while reducing labor costs. In this process, the old is discarded without ceremony, swept away by the tidal forces of competition.

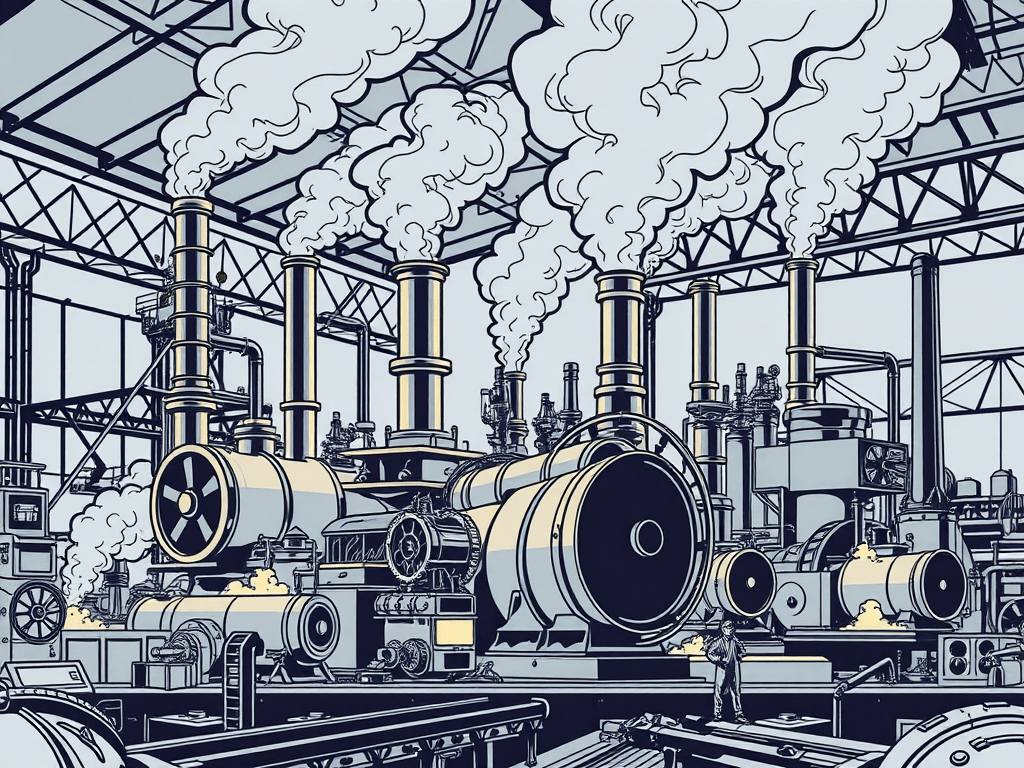

The Industrial Revolution: Capitalism’s Big Bang

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries provides the most striking illustration of this phenomenon. It was here, in the soot-choked factories of Manchester and Birmingham, that the revolutionizing of the means of production transformed not just economies but the very fabric of society. Steam engines replaced hand tools, and assembly lines supplanted artisanal crafts. These changes were not merely quantitative but qualitative; they redefined what it meant to labor, to live, and to exist in a world dominated by machines.

Take, for instance, the textile industry. The spinning jenny, power loom, and cotton gin multiplied output exponentially, reducing the need for skilled labor and rendering traditional weavers obsolete. The consequences were both liberatory and devastating. On one hand, goods became cheaper and more accessible, fueling markets and stimulating further innovation. On the other, millions were uprooted from rural villages and thrust into urban slums, their lives now governed by the merciless rhythms of the factory clock.

The Logic of Capital: Innovation as Necessity

This ceaseless innovation is not optional; it is structural. Capitalism’s survival depends on it. In a competitive market, stagnation is death. A capitalist who fails to innovate, to produce goods more cheaply or efficiently than their rivals, is doomed to extinction. This relentless pressure explains why capitalism has proven so adept at generating technological advances and why it has spread like wildfire across the globe.

Consider the railroad, that quintessential symbol of capitalist modernity. Its construction in the 19th century revolutionized the transportation of goods and people, shrinking distances and annihilating local markets. The railroads did not arise from some altruistic desire to connect humanity; they were built by capitalists seeking to exploit new markets, reduce costs, and expand their profits. And yet, in doing so, they reshaped the world in ways that transcended their creators’ narrow intentions, laying the groundwork for industrialization in places as disparate as the American Midwest and colonial India.

The Double-Edged Sword of Progress

But what of the human cost? For every steam engine that unleashed prosperity, there were countless workers crushed by the gears of the new system—both figuratively and, quite often, literally. The revolutionizing of the means of production does not unfold in a moral vacuum; it is accompanied by dislocation, exploitation, and ecological destruction. The Enclosure Acts of 18th-century England, which privatized common lands and drove peasants into the cities, were as much a part of capitalism’s birth as the invention of the power loom. In the name of progress, entire ways of life were obliterated, and the social bonds that once tethered people to community and tradition were dissolved.

Even today, we see the same pattern. Automation, artificial intelligence, and the gig economy are merely the latest chapters in this ongoing saga. Each promises to increase productivity and reduce costs, but at what price? Workers in precarious industries face a future of uncertainty, while the natural world groans under the weight of unsustainable extraction.

Capitalism’s Contradiction

And here we arrive at capitalism’s great contradiction. While it demands the constant revolutionizing of the means of production, this very process undermines its stability. New technologies displace workers faster than markets can absorb them, creating cycles of overproduction and underconsumption. Marx called this the “crisis of overproduction,” wherein capitalism generates wealth on one hand and poverty on the other. The same innovations that increase productivity also concentrate wealth in fewer hands, exacerbating inequality and sowing the seeds of social unrest.

Conclusion

The revolutionizing of the means of production is both capitalism’s defining strength and its Achilles’ heel. It has unleashed unprecedented technological and economic progress, transforming the world in ways that would have been unimaginable under previous systems. Yet this progress is not without its victims, nor its contradictions. The same process that fuels capitalism’s expansion also undermines its foundations, creating a system that is as unstable as it is dynamic.

What remains, then, is the question of whether this process can be reconciled with the values of justice, equality, and sustainability. Can capitalism survive its own contradictions, or will the forces it has unleashed ultimately demand a new system? Marx believed the latter, and history, for all its complexities, has yet to decisively prove him wrong. As we stand on the cusp of new revolutions in production—from artificial intelligence to biotechnology—the question looms larger than ever. Will we harness these forces for the common good, or will they continue to serve the narrow interests of capital? Only time, and perhaps history’s next great upheaval, will tell.

Leave a comment