Art, like religion and politics, occupies a space in human culture that is both exalted and contested. Its origins are deeply entwined with the material conditions of life, yet its effects often seem to transcend those very conditions. This tension has been a fruitful domain for Marxist thought, which seeks to interrogate the nature of art, its production, and its place within the broader tapestry of economic and social relations. But, as is often the case, the Marxist perspective on art is as illuminating as it is prone to distortion, both by its critics and its overzealous adherents.

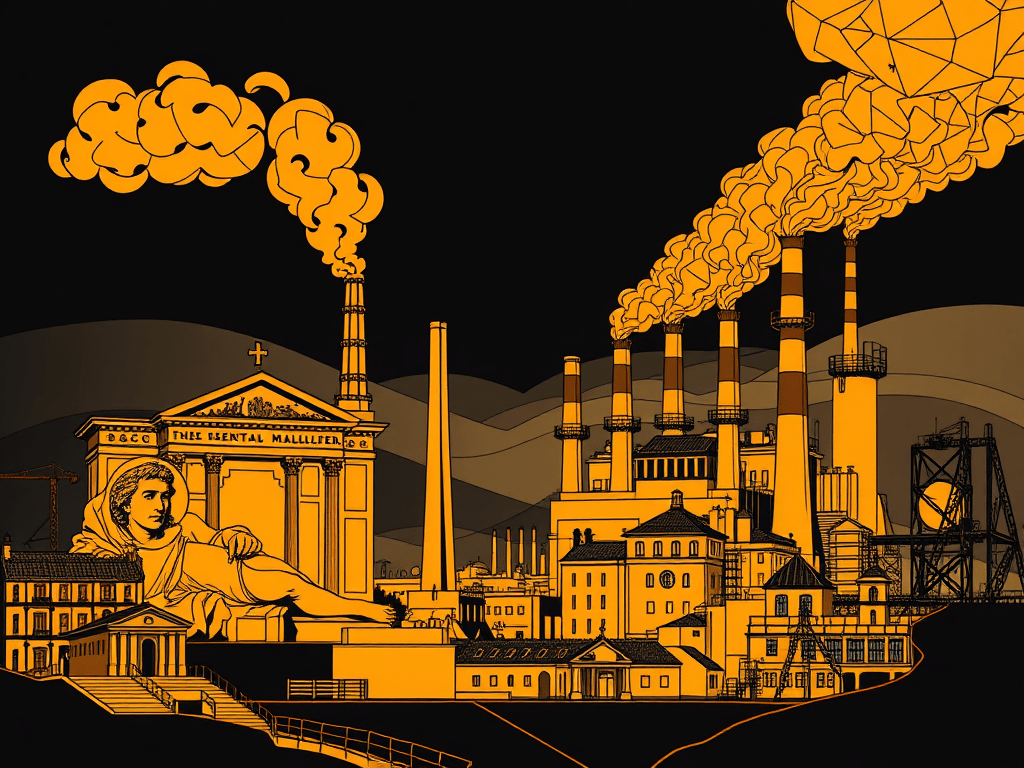

At its core, the Marxist view of art rests on the principle that the material conditions of a society—its mode of production, class relations, and economic structures—determine its ideological superstructure. Art, in this schema, is not an autonomous realm floating freely above society but an integral part of that superstructure, shaped by and reflective of the material base. This insight, for all its simplicity, strikes a devastating blow to the Romantic ideal of the artist as an isolated genius channeling divine inspiration. Instead, the Marxist view places the artist squarely within the world, bound by the contradictions and conflicts of their time.

Take, for instance, the towering achievements of Renaissance art. The works of Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and their contemporaries are often celebrated as the apotheosis of human creativity. Yet, the Marxist analysis compels us to ask: why the Renaissance, and why then? The answer lies not in some mystical eruption of genius but in the material transformation of European society—namely, the rise of the bourgeoisie, the expansion of trade, and the emergence of a new economic order. The Renaissance artists were not merely expressing universal truths; they were articulating the aspirations, anxieties, and contradictions of a world in flux.

However, to suggest that art is merely a reflection of economic conditions would be to flatten its complexity and render it a sterile exercise in propaganda. The Marxist view, properly understood, does not reduce art to economics but rather situates it within the totality of human relations. Art is both a product of its time and a force that can shape consciousness, challenge norms, and inspire action. This dialectical relationship—between base and superstructure, between artist and society—is where Marxism achieves its most profound insights.

Consider the works of Charles Dickens, a writer often celebrated for his moral vision and social critique. A Marxist reading of Dickens would acknowledge that his novels, while exposing the brutalities of industrial capitalism, were also shaped by the very system they critiqued. Dickens’s works do not stand outside history; they are saturated with the contradictions of Victorian England. Yet, his ability to illuminate these contradictions, to render them vivid and immediate, gives his work a revolutionary potential. Art, in this sense, becomes a site of struggle—a space where the tensions of the present can be revealed and, perhaps, transcended.

Of course, Marxism is not without its blind spots and dogmas. The Stalinist insistence on “socialist realism,” for example, was a grotesque perversion of Marxist aesthetics, reducing art to a crude instrument of state propaganda. Such distortions betray a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of art in human life. Art cannot be commanded or conscripted; it must remain, at least in part, an act of freedom—a freedom that is always constrained by material conditions but never entirely determined by them.

It is this interplay between freedom and constraint that gives art its enduring power. While the artist cannot escape history, they can, through their work, reveal its mechanisms and imagine its alternatives. Marx himself, though not primarily an aesthete, understood this. His occasional writings on art display a deep appreciation for its capacity to capture the human condition in ways that pure theory cannot. Marx recognized that art, at its best, does not merely reflect the world; it critiques it, envisions its transformation, and, in doing so, participates in the struggle for a better future.

In the final analysis, the Marxist view of art is not a straitjacket but a lens—one that allows us to see the connections between beauty and brutality, between creation and exploitation, between the artist and the world they inhabit. It reminds us that art is not a luxury or a diversion but a vital part of the human experience, bound up with the same forces that shape our lives and our societies. To engage with art through a Marxist lens is not to diminish its mystery but to enrich its meaning, to see it as both a mirror and a hammer—a reflection of the world and a tool for its remaking.

Leave a comment