Eighth in a series of reflections on my thoughts after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

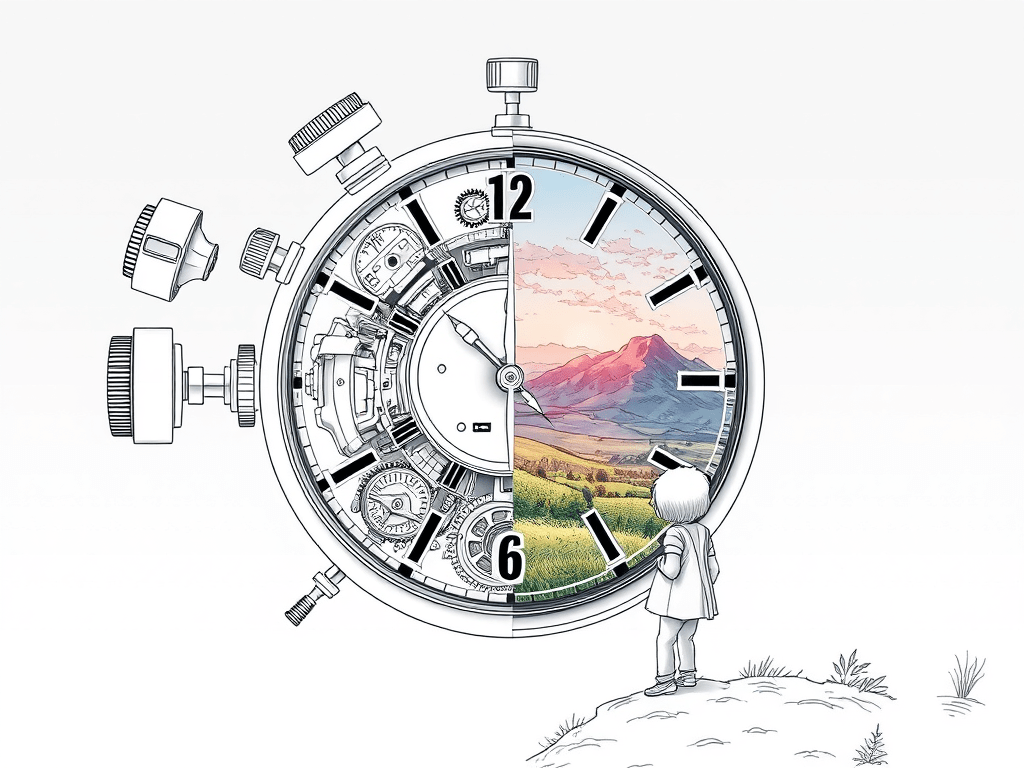

The dogma of mechanistic materialism, for all its claims to intellectual rigor, represents a peculiarly stunted view of reality. It is the philosophy of the pedant, the worldview of the unimaginative, and the creed of those who mistake the skeleton for the living organism. Like a child dismantling a clock to understand time, the mechanistic materialist believes that by reducing existence to its smallest components, one has thereby explained the whole. This reductionism, while occasionally useful as a method, becomes utterly pernicious when elevated to an ideology. Let us examine why.

Materialism, in its broadest sense, has a noble pedigree. It emerged as a necessary corrective to the airy speculations of metaphysics and theology, grounding our understanding of the universe in observable phenomena and measurable facts. The materialist tradition, from Democritus to Marx, has been instrumental in liberating humanity from the tyranny of superstition and the fog of mysticism. It has taught us to look not to the heavens for answers but to the earth, to the physical realities that shape our existence. In this sense, materialism is not merely a philosophy but an act of intellectual courage—a declaration that we will confront reality as it is, not as we wish it to be.

But courage without nuance is recklessness, and here lies the failure of mechanistic materialism. It mistakes the map for the territory, the description for the essence, the mechanism for the meaning. In its obsession with causality, it reduces the richness of existence to a series of inert processes, robbing reality of its texture, its depth, and, dare I say, its mystery. The human mind, for example, is not merely a collection of neurons firing in predictable patterns. It is a site of creativity, contradiction, and transcendence—a phenomenon that cannot be fully captured by diagrams of synaptic activity. To insist otherwise is not science but scientism, the dreary dogmatism of those who believe that what cannot be quantified does not exist.

One of the most galling aspects of mechanistic materialism is its implicit arrogance. It assumes that all questions worth asking can be answered by its methods, that all truths worth knowing are reducible to the language of physics and chemistry. It dismisses art, literature, and philosophy as mere epiphenomena—pretty but irrelevant decorations on the cold, hard structure of reality. This is not just wrong; it is intellectually impoverished. The Mona Lisa is not merely pigment on canvas, and Hamlet is not reducible to the chemical composition of the ink in which it was written. To understand these works solely in material terms is to miss their essence entirely.

Even worse, mechanistic materialism betrays a peculiar form of cowardice. It is a philosophy that cannot tolerate ambiguity, paradox, or the limits of its own understanding. It demands certainty, and when certainty is unattainable, it retreats into the comforting illusion that what cannot be explained does not matter. This is the attitude of the fundamentalist, not the seeker. A truly curious mind embraces the unknown, revels in the complexity of the universe, and refuses to be satisfied with simplistic answers.

And let us not overlook the ethical implications of mechanistic materialism. If all phenomena are reducible to physical processes, then where, exactly, does one locate human dignity, moral responsibility, or the idea of justice? Mechanistic materialists might argue that these concepts are mere social constructs, the byproducts of evolutionary pressures and biochemical imperatives. But this explanation, while clever, is also profoundly unsatisfying. It reduces the most profound aspects of human experience to mere artifacts, stripping them of their meaning and weight. To say that love is “just” a chemical reaction is not to explain it but to diminish it.

This is not a call to abandon materialism altogether. Far from it. Materialism, when properly understood, is a vital tool—a framework that grounds our understanding of the physical world and enables us to distinguish fact from fantasy. But it is only a tool, not a totalizing doctrine. The error of mechanistic materialism lies in its inability to recognize its own limitations, its refusal to admit that there are dimensions of reality—subjective, experiential, aesthetic—that cannot be fully apprehended by its methods.

In the end, the problem with mechanistic materialism is not that it is wrong but that it is incomplete. It is a philosophy that has forgotten the wisdom of Shakespeare: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” The task of the thinking person is not to reject materialism but to transcend its narrowest forms, to seek an understanding of reality that is as expansive, as nuanced, and as vibrant as reality itself. Anything less is not merely inadequate; it is an abdication of the very curiosity and wonder that make us human.

Leave a comment