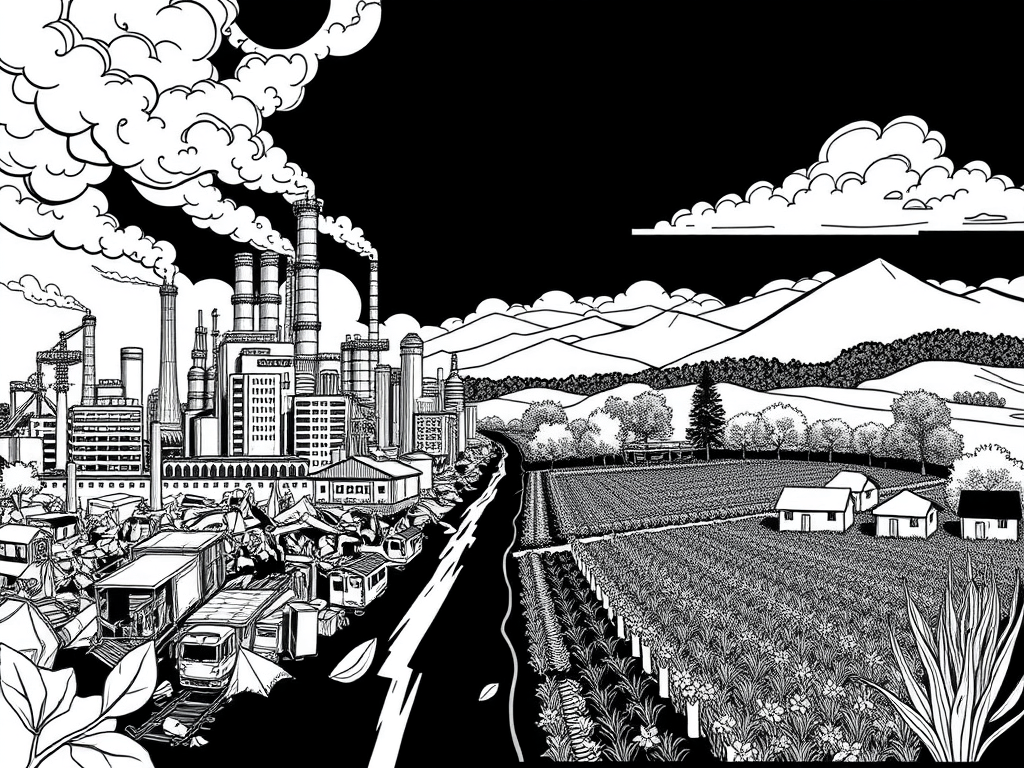

Climate change is a systemic crisis rooted in the socio-economic structures of global capitalism. Eco-socialism argues that only a transformation of these structures – toward collective ownership, democratic planning, and ecological stewardship – can avert environmental collapse. Marxist ecological theory provides vital tools for this analysis. In Marx’s terms, capitalism produces a “metabolic rift” in the relationship between society and nature – disrupting natural cycles through relentless pursuit of profit. Marxists like John Bellamy Foster have shown that the metabolic rift explains how capitalist agriculture exhausts soils and emits carbon while hoarding resources in cities, undermining long-term ecological health. Others, like James O’Connor, argued that capitalism’s “second contradiction” means it undermines its own natural foundations – destroying ecosystems that are the basis of production. In short, capitalist accumulation requires perpetual growth and commodification of nature, which inevitably drives climate and ecological crises.

Eco-socialist thinkers (Foster, Paul Burkett, Alfred Schmidt, etc.) have demonstrated that Marx’s work contains a critical green sensibility: Marx insisted that “man lives on nature… and he must remain in continuous interchange if he is not to die.” Through recent scholarship, ecological Marxism has emerged as a coherent framework. It rejects the old assumptions that Marx was indifferent to nature; instead, it highlights Marx’s insight that environmental degradation and social exploitation are intertwined. As Andreas Malm notes, “the materialist epiphany” of many on the left is recognizing that “literally everything is at stake in the ecological crisis” – including revealing the “basic contradiction between capitalism and sustainability.” Foster, Burkett and others have laid out the metabolic rift school, showing how capital creates multiple “ecological rifts” by severing community and land (e.g. capitalist farming exporting soil nutrients to cities) and by imperialist resource extraction overseas. They argue these rifts manifest in climate change, deforestation, soil depletion, ocean dead zones, and public health crises.

Eco-socialism thus asserts that capital accumulation’s logic – growth, profit, and private ownership – is incompatible with ecological balance. Capitalism’s “endless quest for profits,” driven by a tiny elite of corporations, has produced most greenhouse gases. A study shows just 100 investor-owned fossil-fuel producers have been responsible for about 71% of global emissions since 1988. This concentration of carbon in the hands of the few illustrates the systemic nature of the crisis: it is a social problem, not one of individual irresponsibility. Liberated from profit, eco-socialist planning could redirect energy and resources toward sustainability.

Socialist Frameworks and Environmental Sustainability

Socialist principles – public ownership, democratic planning, collective responsibility – offer alternative mechanisms for meeting human needs sustainably. In a socialist model, energy and resources are treated as social commons, not profit commodities. Public ownership of utilities and natural resources can prioritize long-term ecological goals over short-term profit. For example, re-nationalizing or creating new publicly owned utilities is increasingly seen as a way to invest in renewables. In Germany, two large electricity firms (EnBW and Steag) were re-nationalized and dozens of new municipal utilities established, motivated by the expectation that state-owned companies will invest more sustainably. Debates in the UK and US have even included proposals to nationalize energy infrastructure for the climate fight.

Similarly, collective planning enables deliberate transitions. As socialist theorist Otto Neurath envisioned a century ago, a democratically planned economy could coordinate disparate sectors in terms of “natural units” (e.g. tons of steel, megawatt-hours, calories of food) rather than abstract profits. Vettese and Pendergrass argue that Neurath’s insight is vital today: planning with ecological criteria would avoid the “pseudorational” profit-driven choices that degrade the environment. A Neurathian plan would allow society to survey “total plans” and democratically decide future priorities, aligning production with environmental limits. The alternative – neoliberal markets – have repeatedly failed to price environmental costs or protect common resources, as even conservative economist Mises conceded (markets rarely safeguard the environment). Eco-socialists agree we need a new socialist theory that explicitly combines planning with ecological insights to overcome this failure.

Under socialism, public and cooperative ownership would enable large-scale investment in low-carbon infrastructure. State or community-owned enterprises need not chase returns for shareholders; they can install renewable generation, retrofit buildings, and build mass transit as a public good. For instance, analyses suggest state-owned utilities would, in theory, make more sustainable investment decisions. In practice, public owners in some European countries have indeed pursued renewables aggressively: many German municipal utilities have mandates to meet certain renewable targets, and even wind up banning coal plants. A recent study finds that historically, public utilities in Europe have been involved in a diverse range of energy strategies, including aggressive renewables targets (e.g. utilities in Munich and others targeting specific renewable shares). Unlike private firms beholden to shareholders, publicly-owned systems could be democratized to reflect community environmental needs.

Economic planning can also accelerate decarbonization by mobilizing resources rapidly and equitably. While Huber and Stafford controversially argued for nuclear-centered planning, others point out that planning need not exclude decentralized renewables. Pirani (2024) emphasizes that decentralized green grids are not inherently incompatible with socialism: “claims that renewables … are inherently inimical to … public ownership or socialist principles, are baseless.” Indeed, socialism can adapt to new technologies and challenge capitalist control over energy. For example, a planned economy could phase out fossil fuel subsidies, curtail polluting industries, and channel investment into green jobs. Economic democracy (workers and communities deciding production) can ensure environmental priorities are not overridden by profit.

Moreover, socialist values promote collective responsibility and sufficiency. Unlike consumerist capitalist culture, a socialist ethos emphasizes meeting needs without endless growth. Public control can implement energy rationing in emergencies, maintain ecosystems as public trusts, and enforce pollution limits without profit derailment. A planned green transition could include guaranteed jobs in conservation, reforestation and renewable energy construction. Nordic social democracies offer a partial example: while not fully socialist, Scandinavian welfare states have deployed generous public resources for climate and social welfare, demonstrating how high social provision can coexist with aggressive decarbonization (though their frameworks remain capitalist in ownership). An ecosocialist state could go further: for instance, decentralized cooperatives might manage forests and fisheries based on ecological principles, while a public Green New Deal could retrain workers in green industries.

Socialism also implies addressing unequal ecological exchange and environmental justice. Capitalism externalizes environmental damage, but a socialist system could internalize environmental costs and redistribute burdens fairly. Socialist policies could compensate communities affected by pollution, fund climate adaptation globally, and assert Indigenous land rights as central (since Indigenous stewardship has historically been most effective at conservation ). Indeed, eco-socialists argue that only a system beyond private profit can equitably bear the costs of climate mitigation – for instance, funding a just transition for coal miners or assisting countries hit hardest by climate disruption.

In sum, socialist principles – democratic planning, common ownership, and collective stewardship – align economic incentives with ecological imperatives. They contrast sharply with capitalist market forces, which require infinite growth and often pit environmental regulation against profitability. As the eco-socialist literature insists, system change (not climate change) is the only path: “we need a fundamental transformation of society to avoid catastrophe,” as activists’ slogan puts it.

Case Studies: Eco-socialist Initiatives in Practice

Cuba: Agroecology and Renewable Targets

Cuba provides a notable example of socialist policy driven by necessity evolving into an ecological advantage. After the Soviet collapse in 1991 (“the Special Period”), Cuba lost its cheap oil and fertilizer imports. This crisis prompted a rapid shift to organic and urban agriculture. As Maurício Betancourt’s quantitative study shows, Cuba’s adoption of agroecology substantially mitigated the metabolic rift. Using UN and World Bank data, Betancourt found that by the 2010s, Cuban crop yields (maize, beans) grew even as synthetic fertilizer use declined – a reversal of the usual global trend. In other words, Cuba decoupled productivity from inputs, suggesting its agroecology restored soil fertility rather than mining it. This implies that socialist-driven farming reforms can increase yields while reducing chemical dependence, an important lesson for sustainable food systems.

Cuba’s socialist government has long combined survival with environmental goals. Its recently updated climate plan (2020) sets explicit renewable energy and land-use targets. For example, Cuba aims to raise its share of electricity from renewables from about 4% today to 24% by 2030. It also plans to expand forest cover to one-third of its land by 2030 (from ~31% in 2016). These targets are ambitious for a small island economy; they reflect strategic planning to reduce imported oil dependency (over 70% of Cuba’s energy now comes from oil). Notably, Cuba links its need for renewables to economic security: fuel imports consume about 30% of Cuba’s import bill, making decarbonization a fiscal imperative. In these plans, the state asserts that wealthier polluters should bear climate costs, echoing the socialist principle of differentiated responsibility.

Cuba’s mixed record reminds us of limitations: it still relies on cheap fossil fuel aid from allies and lacks capital for green investment. But under socialism, Cuba has leveraged international solidarity and domestic mobilization to weather crises with relatively low per-capita emissions. Its experience suggests that a socialist government can pivot towards sustainability by reshaping agriculture, transportation, and energy according to public needs (see also Cuba’s investment in solar parks and plans for 700 MW solar capacity ). In short, Cuba illustrates how even a resource-poor socialist economy can innovate ecologically through state-led planning and community mobilization.

Indigenous-led Stewardship and Buen Vivir

Around the world, Indigenous movements illustrate eco-socialist principles in practice through communal land management and environmental rights. Globally, indigenous territories cover roughly 20% of the Earth’s land but harbor about 80% of its remaining biodiversity. Studies in Canada, Australia, and Brazil show that Indigenous-managed lands are often richer in species than even formal parks, and better protect threatened wildlife. These figures underline a socialist-friendly insight: when communities collectively steward the land and respect reciprocity with nature, conservation flourishes. Indigenous stewardship often embodies communal ownership, long-term horizons, and relational ethics – all antithetical to capitalist exploitation.

Policies recognizing Indigenous rights have proven crucial. For example, many Latin American constitutions now enshrine Pachamama (“Mother Earth”) rights, influenced by socialist leaders allied with Indigenous movements. Ecuador’s 2008 Constitution declares the aim of a “new form of public coexistence… in harmony with nature” (the buen vivir, or “good way of living”). Bolivia’s 2011 Law of Mother Earth was the first to grant nature legal rights. These laws grew out of coalitions between socialist parties and indigenous groups (e.g., the indigenous president Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador partnering with indigenous activists ). They represent an eco-socialist turn: redefining development away from extractivism toward ecological balance.

In practice, many Indigenous communities pursue community-based conservation. Examples include the Surui tribe in Brazil using satellite monitoring to stop illegal logging, or First Nations in Canada establishing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) to manage their lands under traditional law. These grassroots initiatives mirror socialist values of collective governance and resource sharing. They also confront capitalist state policies: for instance, Indigenous activists worldwide often oppose mega-projects that threaten ecosystems, echoing eco-socialist critiques of “development” that serves corporate profit.

Latin American Eco-Socialist Policies

Beyond Indigenous governance, several Latin American experiments explicitly blend socialism and ecology. The Buen Vivir agenda, enshrined by leftist governments, is one case. In Ecuador and Bolivia, successive “Pink Tide” administrations championed policies like treating nature as a rights-bearing entity. For instance, by rejecting oil drilling in the Yasuni national park (albeit imperfectly), these states at times prioritized environmental limits over profit. RapidTransition Alliance notes that Ecuador’s leaders proclaimed a “harmony with nature” constitutionally, reflecting the Quechua idea of sumak kawsay (living well). Bolivia similarly led the UN in declaring a Mother Earth Day and codified ecosystem rights. These policies aim to move beyond neoliberal extractivism toward “ecological balance” as a national goal.

Of course, these experiments have had mixed results. Both governments still depended on resource exports (oil, gas, mining), and economic pressures have sometimes forced compromises. But the attempt to fuse socialist governance with environmental protection is significant. It shows that a state rooted in socialist or decolonial rhetoric can at least rhetorically prioritize the environment in law and planning. For eco-socialists, such cases offer lessons on the importance of embedding ecological values in constitutions and economic models, even under conditions of limited power.

Other Examples: Rojava and Local Initiatives

Beyond formal states, some grassroots movements illustrate eco-socialist ideas. In Rojava (Kurdish Syria), the grassroots “Democratic Federation of Northern Syria” was founded on principles of social ecology (inspired by Murray Bookchin). Rojava’s charter explicitly includes ecology as a pillar alongside gender equality and direct democracy. In practice, communes run community gardens, irrigation projects, and recycling cooperatives. An “Internationalist Commune” in Rojava trains volunteers in environmental awareness and local farming. This reflects an eco-socialist model of bottom-up communal organization of production. Although Rojava faces immense political pressures, its example shows that even amidst conflict, people can attempt to build sustainable, collectively run systems.

Similarly, many urban and rural communities worldwide adopt co-ops and municipal programs that resonate with socialist values. Cities like Kamikatsu in Japan have near-zero waste policies based on collective action; in India, the Chipko forest movement combined environmentalism with rural community struggle. In Europe, workers’ cooperatives and eco-villages embody social ownership plus sustainability. These instances illustrate that collective organization can lead to greener lifestyles: shared transit reduces emissions, community ownership of forests prevents deforestation, etc.

Marxist Ecology: Capitalism vs Environmental Degradation

Marxist ecological thought deepens our understanding of how capitalism causes degradation. It highlights unequal ecological exchange: wealthy nations externalize pollution and resource extraction to poorer regions (a form of “ecological imperialism”), while dumping waste back home. Foster and others link this to colonialism and finance capital. For example, ecologically, the conquest of Latin America and Africa was also an expropriation of nutrients and ecologies on a global scale. Michael Roberts and Jason Moore expand on this “world-ecology” analysis.

Andreas Malm’s work adds a historical-materialist angle: in Fossil Capital (2016), he argues that capitalists’ choices determined our dependence on carbon. He contends that capitalism’s expansion in the 19th century was not driven by energy necessity alone, but by a social preference to invest in coal mines rather than efficiency; as a result, we locked-in an infrastructure that still drives emissions. This underscores that capitalist class decisions shape energy paths, not impersonal market forces. Malm calls for urgent state-led action (even on controversial tactics) to break this lock-in. He has even provocatively argued for an “ecological Leninism” – using decisive state power to override the logic of profit in service of the climate.

Other Marxist critics point out that capitalist crises often exacerbate environmental harm. For instance, neoliberal austerity can slash environmental enforcement, while recessions may kill green investments. The “treadmill of production” thesis (John Bellamy Foster et al.) notes that competition forces all firms to externalize costs to survive, so pollution is endemic under capitalism. Workers’ struggles under capitalism have often been pitted against environmental demands (“jobs vs environment”), whereas a socialist economy could break that tradeoff by sharing resources and prioritizing public welfare.

It is also worth noting internal critiques: some Marxists warn that pre-21st-century socialist states (e.g. Stalinist USSR, Maoist China) often practiced environmentally destructive development. Socialism is not a panacea unless explicitly ecological. Eco-socialists therefore emphasize democratic accountability and polycentric management even within socialism, rather than top-down tyranny. They point to ecological economics and “social reproduction” as fields that should inform socialism.

Conclusion

The climate crisis is a systemic crisis of the capitalist system. Eco-socialism argues that only through socialist transformation—grounded in Marxist ecological insights—can humanity organize production, consumption, and growth in line with Earth’s limits. In Marxist terms, capitalism’s metabolic rift must be mended by a system that recognizes society as part of nature, not as its master. Socialist frameworks of public ownership, democratic planning, and collective stewardship align human economies with environmental sustainability.

Real-world examples offer both inspiration and caution. Cuba’s agroecology and renewables goals, Indigenous land management worldwide, and Latin America’s rights-of-nature policies show that socialist or communal approaches can yield ecological benefits. At the same time, these cases reveal challenges: global markets, entrenched power, and resource constraints can limit even well-intentioned socialist programs. Thus, building an eco-socialist future requires vigilance to democratic values and environmental science.

Ultimately, eco-socialism rests on the idea that sustainability and equity are inseparable. By putting society in democratic control of the economy and the environment, socialist principles can turn climate ambitions into reality. As Stewart and Taylor emphasize, today’s movements understand that “system change, not climate change” is the slogan – meaning that only by uprooting capitalist accumulation and instituting an eco-socialist alternative can we hope to solve the climate crisis.

Leave a comment