An ongoing series of reflections of my thoughts on historical materialism after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

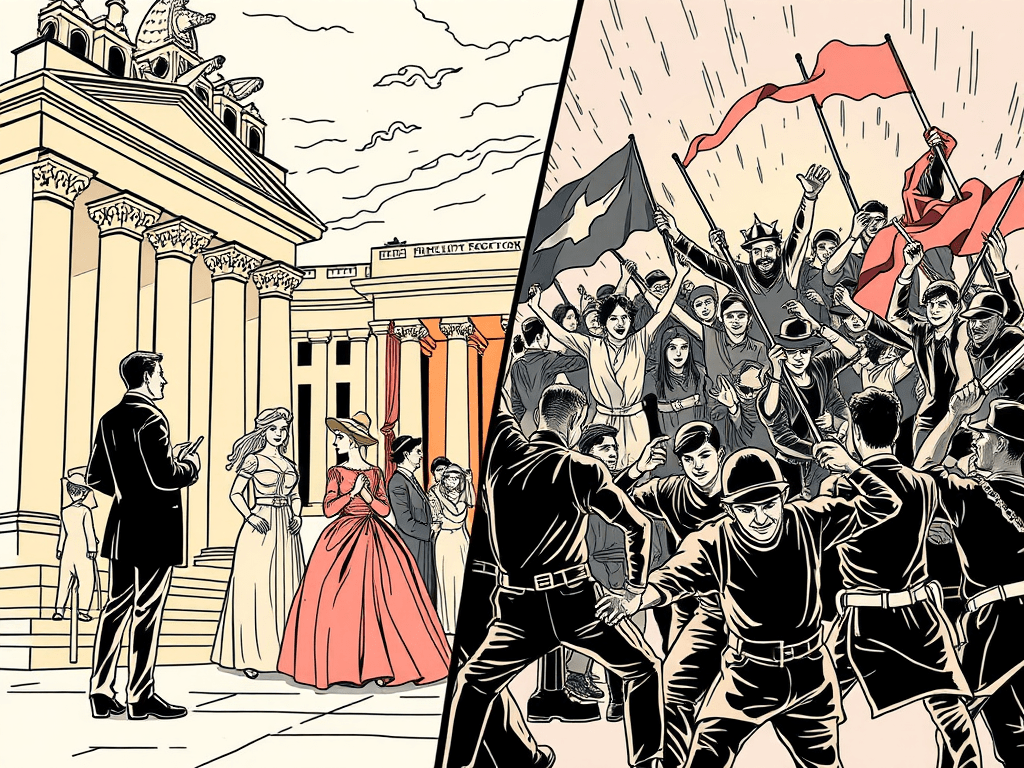

It is one of the more intriguing peculiarities of history that revolutions, ostensibly seismic events that purport to overhaul the old and usher in the new, often contain within them the seeds of continuity. Not all revolutions are created equal, and the contrast between the bourgeois and proletarian revolutions could hardly be more stark. One seeks to reform the structure of power, the other to dismantle it entirely. This distinction, subtle on the surface, represents a chasm in political philosophy, historical practice, and the very essence of human aspiration.

Let us begin with the bourgeois revolutions, those tidy affairs of commerce and constitutionalism. The French Revolution of 1789, the English Civil War of the mid-17th century, and even the American Revolution of 1776 belong firmly in this category. These were uprisings of the middling sort, those with enough education to read Locke and Rousseau but not enough status to avoid paying taxes. The bourgeois revolutions, for all their fiery rhetoric, were essentially about redistribution within an existing hierarchy. Property rights remained sacred, private capital unchallenged, and the ultimate victory was not that of the downtrodden but of those industrious enough to climb a rung or two higher on the ladder.

What did they want, these bourgeois rebels? They sought liberation not from hierarchy itself but from the tyranny of an old guard that had ceased to function effectively. Theirs was a complaint not against inequality as such but against the wrong kind of inequality: privilege unearned, entitlement inherited rather than earned. They replaced kings with parliaments, nobles with merchants, and divine right with market logic. The slogans of “liberty, equality, fraternity” were, in practice, confined to those who already had the means to participate. For women, the working class, and colonized peoples, the promises of the bourgeois revolutions remained an empty echo.

Contrast this with the proletarian revolution, which is an altogether more terrifying prospect for the ruling classes. Here, the aim is not to adjust the balance of power but to upend it entirely. The proletariat, by definition, owns nothing but its labor. It is the class of the dispossessed, the forgotten, and the exploited. When it rises, it does not do so to tinker with the mechanisms of state; it rises to burn them to the ground.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 is the archetype of this category. Unlike its bourgeois predecessors, it was not a revolt of merchants against monarchs but of workers and peasants against the entire edifice of capitalist exploitation. For the proletariat, the revolution is not merely a political event; it is a metaphysical one. It seeks to rewrite the very rules by which society functions, abolishing private property, dismantling the class system, and replacing market competition with collective ownership.

Leave a comment