An ongoing series of reflections of my thoughts on historical materialism after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

Among the many brilliant speculations and rigorous analyses authored by Karl Marx, the Asiatic mode of production (AMP) occupies a curiously marginal place. It is both a concept touched upon and a theoretical shadow that Marx himself left largely unelaborated.

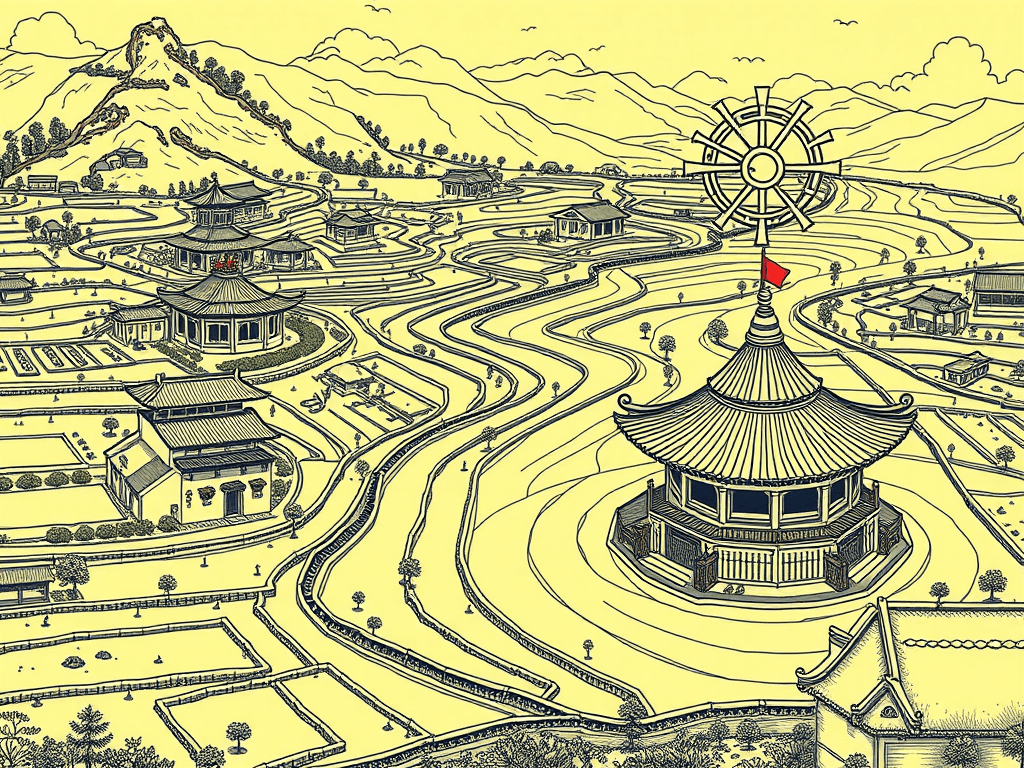

Marx described the AMP in his early writings as a peculiar form of socioeconomic organization. Unlike the feudal or capitalist systems of Europe, the AMP was characterized by centralized state control over land and resources, an absence of private property in the Western sense, and a social structure dominated by despotic rulers. The mode was said to flourish in regions where irrigation agriculture required large-scale cooperation, such as ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and India. In such societies, Marx observed a lack of the dialectical conflict between distinct classes that he saw as the engine of historical change. Instead, these “oriental despotisms” were portrayed as static, almost timeless entities, impervious to the revolutionary ruptures that typified Europe.

This conception, however, remained peripheral to Marx’s writings. For Marx, history unfolded through a series of revolutionary transformations driven by contradictions between productive forces and relations of production. Yet, the AMP seemed to lack the dynamic interplay of opposing classes. Where was the proletariat to overthrow the bourgeoisie? Where was the feudal peasant rising against the lord? The Asiatic societies appeared to Marx as stagnant, locked in an eternal present—a frustrating anomaly in his otherwise dialectical schema.

Marx was writing for a European audience, engaged in the revolutionary struggles of his time, and seeking to demonstrate the inevitability of socialism as the successor to capitalism. To divert his energies toward analyzing pre-capitalist modes of production in distant lands would have been an indulgence ill-suited to his purpose. Europe, with its industrial proletariat and burgeoning bourgeoisie, was the crucible of revolution. The Asiatic mode, by contrast, was an intellectual curiosity—an interesting deviation but hardly a centerpiece of his theory.

Despite his penetrating critique of imperialism and industrial capitalism, Marx, like many of his contemporaries, was shaped by the intellectual prejudices of his age. The AMP’s portrayal as static and despotic reflected a broader Orientalist discourse that sought to contrast Europe’s “progress” with the perceived “backwardness” of the East.

The AMP offers a lens through which to critique contemporary power structures. In an age when authoritarianism and state capitalism flourish in various forms, the concept of centralized, despotic control over resources resonates anew. The AMP, with its emphasis on state dominance and communal labor, invites us to reconsider the interplay of power, property, and production in societies beyond the West.

To wrestle with the AMP is to confront the complexity of history, the diversity of human societies, and the challenge of building a theory that encompasses them all. It is, in short, to engage with Marx at his most provocative and his most incomplete—a task as necessary now as it was in his own time.

Leave a comment