An ongoing series of reflections of my thoughts on historical materialism after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

The question of whether humans are naturally selfish beings is one that ricochets through the annals of philosophy, science, and political theory with all the subtlety of a battering ram. To consider this question through the lens of a Marxist framework—where the means of production shape the very marrow of our consciousness—is to grapple not with some primordial essence of “selfishness,” but rather with the conditions that breed, encourage, and reward it. For it is not in the crucible of the natural world, but within the exploitative structures of class society, that selfishness as we know it is forged.

Human Nature and Historical Materialism

Marxism, grounded in historical materialism, teaches us that there is no immutable “human nature” independent of the socio-economic conditions under which we live. To attribute selfishness to the essence of humanity is to commit the fallacy of ahistoricism, ignoring the myriad ways that human behavior has shifted over time. The notion of humans as selfish creatures is not an objective truth but a reflection of the capitalist ideology that permeates our society, which glorifies individual accumulation at the expense of collective welfare.

Consider the contrast between pre-capitalist societies and the capitalist order. In many indigenous and communal societies, cooperation rather than selfishness is the governing principle. Property was often held in common, and the survival of the group depended on mutual aid. Anthropological studies of hunter-gatherer communities reveal systems of food sharing that are fundamentally at odds with the Hobbesian vision of humanity as solitary, nasty, and brutish. Were these societies populated by a different species of homo sapiens? Or is it the economic superstructure of capitalism that molds modern humans into the competitive, acquisitive beings we recognize today?

Selfishness as a Product of Capitalism

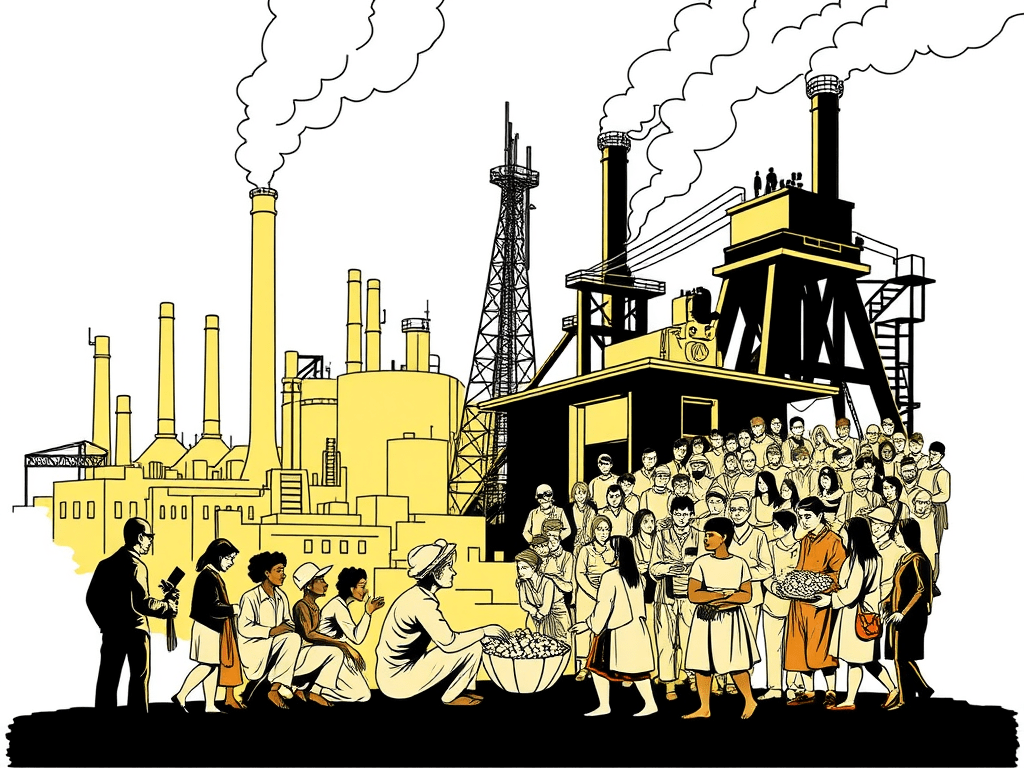

Capitalism, with its relentless drive for profit, creates the conditions under which selfishness is not only cultivated but necessary for survival. The worker competes with his fellow laborers for scarce jobs; the small business owner must undercut his peers to stay afloat; the corporation must grow or die. This is not a reflection of human nature but of systemic coercion. Capitalism demands selfishness in the same way that a factory demands raw materials—without it, the machinery ceases to function.

Take, for example, the enclosures of common lands in early modern England. The privatization of shared resources displaced peasant communities and forced individuals to fend for themselves in an emerging market economy. What was once a shared responsibility—feeding the village, maintaining the commons—became a zero-sum game where one person’s gain necessitated another’s loss. Here, selfishness was not an innate human trait but a response to the structural violence of capitalism’s birth pangs.

The False Morality of Altruism in Capitalism

Even capitalism’s supposed altruism—charity, philanthropy, and the like—betrays its inherent selfishness. The billionaire who donates a fraction of his fortune to a hospital wing does so not out of magnanimity but out of a desire for tax breaks, social prestige, and a clean conscience. Meanwhile, the conditions that allowed him to amass such wealth remain unchanged. As Marx would remind us, this is ideology at work: a system that perpetuates exploitation while masking it with the veneer of generosity.

Yet, humans under capitalism do not behave selfishly in all contexts. Consider the spontaneous solidarity that emerges in times of crisis—natural disasters, revolutions, strikes. When the ordinary constraints of capitalism are suspended, humans reveal an extraordinary capacity for mutual aid and sacrifice. In such moments, we see the outline of a different social order, one where selfishness is not the dominant mode of being.

The Revolutionary Potential of Human Solidarity

If selfishness is a product of capitalism, then it follows that it can be overcome through revolutionary change. Socialism, which seeks to abolish the conditions that breed selfishness, offers the possibility of a society where cooperation and collective welfare replace competition and greed. The Paris Commune of 1871, however brief its existence, demonstrated how ordinary people, freed from the tyranny of the capitalist state, could organize themselves for the common good. In such a society, the question of whether humans are naturally selfish becomes irrelevant; what matters is the material conditions that allow solidarity to flourish.

Conclusion

To ask whether humans are naturally selfish beings is to pose the wrong question. It is not nature but history, not biology but economics, that shapes our behavior. Under capitalism, selfishness is not a sin but a survival strategy. Under socialism, it can be discarded like the outmoded relic of a darker age. In this sense, the question is not whether humans are selfish, but whether we possess the courage and imagination to create a society that allows us to be otherwise. For as Marx reminds us, it is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but their social being that determines their consciousness. And what a liberation it would be to finally leave selfishness behind.

Leave a comment