Boxing Day, that curious appendage to Christmas, stands as a peculiar yet revealing phenomenon of Western culture. Officially, it’s the day after Christmas—a moment designated for charitable giving and the distribution of boxes of alms to the less fortunate. But like most cultural relics, its origins are not as important as the meaning we ascribe to it today. As one sifts through its layers of history, tradition, and modern consumerism, Boxing Day emerges as a holiday rife with contradictions and opportunities for philosophical inquiry.

First, we must confront its name. Boxing Day. The word “boxing” evokes images of pugilism, of combatants trading blows in a ring—a ritual of brute competition. How ironic, then, that the holiday itself purports to symbolize generosity and goodwill. This tension between struggle and sharing is not merely semantic; it reflects the deeper contradictions of human society. The Christmas holiday, which Boxing Day follows like a hungover shadow, is itself a celebration of excess cloaked in a rhetoric of humility. The gifts, the feasts, the decorations—these are the offerings of a society luxuriating in its prosperity while murmuring the name of a poor carpenter’s son born in a stable. Boxing Day is no different. It suggests a duty to the downtrodden but is increasingly celebrated through a frenzy of consumerist indulgence: the post-Christmas sales.

This brings us to the question of charity, that cornerstone of Boxing Day’s purported philosophy. Charity, in its ideal form, is a recognition of shared humanity—a gesture that affirms the inherent dignity of all, regardless of circumstance. Yet in practice, charity often serves to reinforce hierarchies. The giver asserts their power, the recipient is reminded of their need, and society pats itself on the back for maintaining an equilibrium that ensures neither revolution nor progress. The Boxing Day tradition of giving “boxes” to the less fortunate is thus both noble and condescending. It is noble because it acknowledges that others suffer; it is condescending because it implies that a day of token generosity can offset a year of systemic neglect.

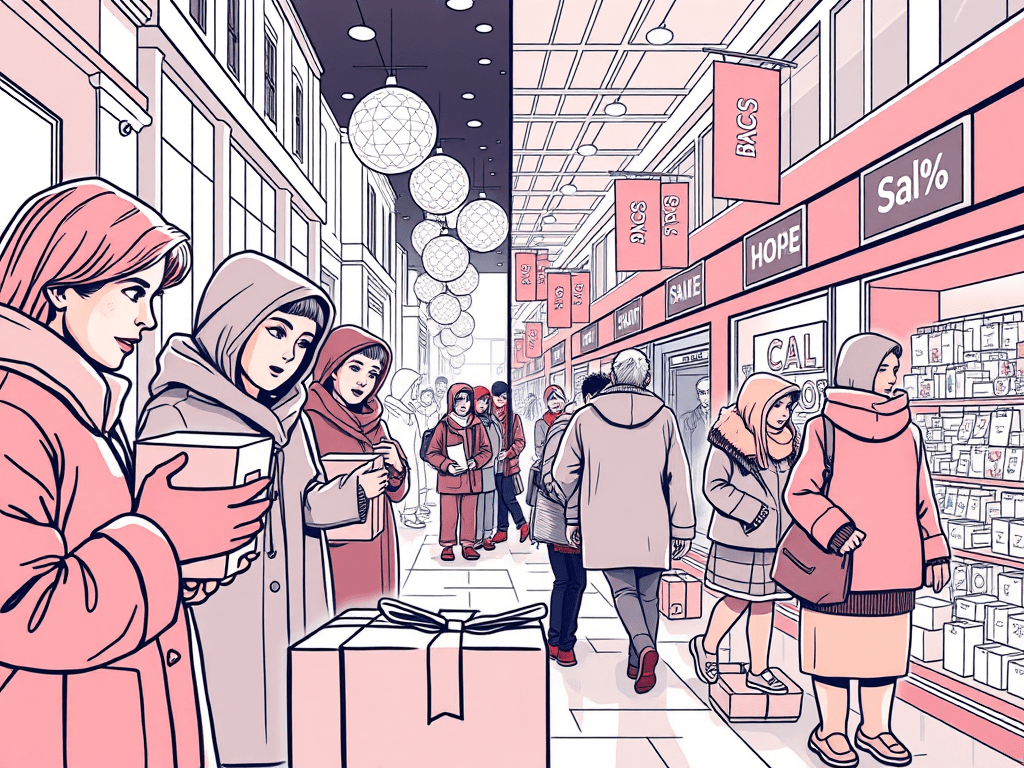

But there is another aspect of Boxing Day that is more honest, if less flattering: its embrace of consumerism. In many countries, Boxing Day has become synonymous with sales, discounts, and the orgiastic pursuit of goods. On this day, the altruistic impulse is supplanted by the hunt for bargains—a spectacle that reveals, with almost anthropological clarity, the priorities of modern life. To criticize this consumerist fervor would be easy, but perhaps too simplistic. After all, the pursuit of material goods is not merely a vice; it is an expression of human aspiration. People do not queue for hours outside a store or wrestle for the last discounted television simply because they are greedy. They do so because they believe, however misguidedly, that these objects will enhance their lives, that they will bring joy, comfort, or status. In this sense, Boxing Day sales are not a degradation of the holiday’s spirit but an extension of it—a reflection of the same human longing for fulfillment that fuels both charity and capitalism.

What, then, is the true philosophy of Boxing Day? It is, at its core, a meditation on the paradoxes of human nature. It is a day that asks us to be generous but tempts us to be selfish; a day that celebrates the spirit of giving while indulging the desire for accumulation. It reminds us that we are creatures of contradiction—capable of both profound empathy and relentless self-interest. And perhaps this is why Boxing Day, like so many of our holidays, endures. It is not a moral lesson or a sacred ritual; it is a mirror. It reflects back to us the messiness of our existence, the tangle of impulses that make us human.

In the end, whether you spend Boxing Day giving to the poor, shopping for yourself, or simply recovering from the excesses of Christmas, the day carries a message worth pondering. It reminds us that our lives are defined not by purity of purpose but by the choices we make within the chaos. And perhaps, in that muddled spirit, Boxing Day is a holiday we all deserve.

Leave a comment