Eleventh in a series of reflections on my thoughts after reading What is Marxism: An Introduction into Marxist Theory by Rob Sewell and Alan Woods. The thoughts, opinions, and any errors are mine alone.

The human spirit is a curious and maddening thing. For centuries, we’ve witnessed masses of people endure profound indignities and injustices, only to rise, as if on a single breath, against what might seem a comparatively minor affront. To the untrained eye, these moments appear irrational, even trivial. Yet to dismiss them as such would be to miss the point entirely, to fail to grasp the combustible cocktail of pride, principle, and pent-up frustration that can ignite even the smallest spark into a blazing conflagration.

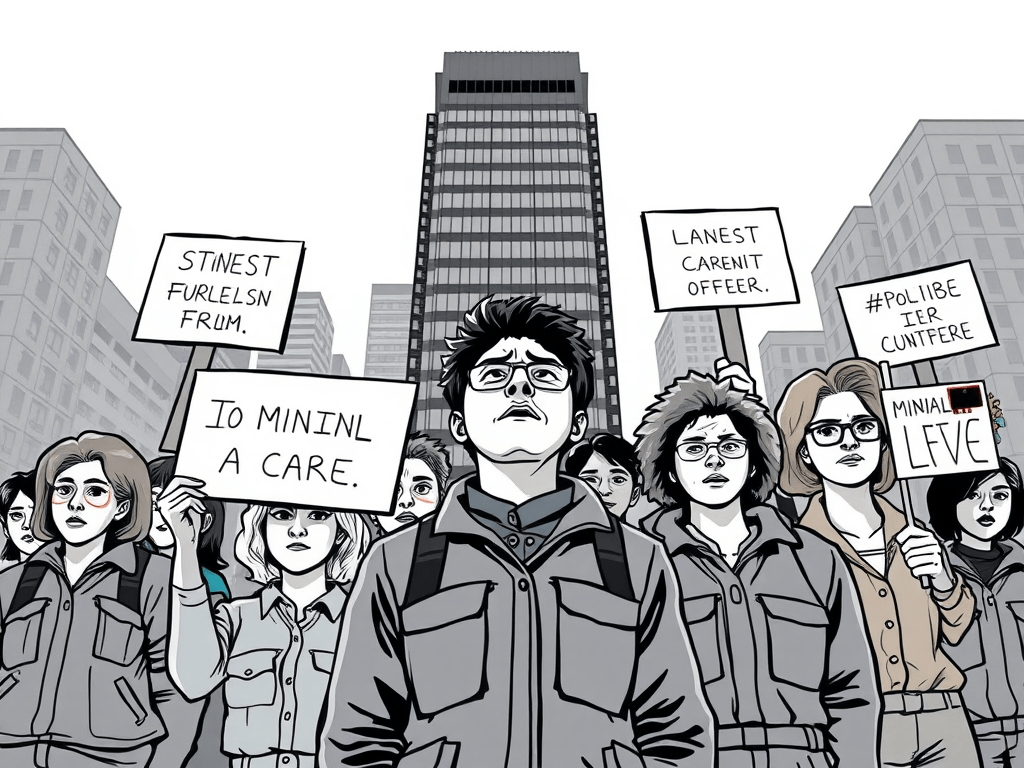

Consider the workplace, that peculiar arena of forced collaboration and hierarchies of dominance. Workers, for all their power in numbers, often endure assaults on their wages, benefits, and dignity with a kind of stoic resignation. Why? Because the forces arrayed against them—corporate bureaucracy, the law, the coercive apparatus of the state—seem so vast and immovable as to make resistance feel futile. The weight of these injustices crushes not just the body but the spirit, reducing people to a state of grim acceptance.

But every chain, as they say, has its weakest link. And every long-suffering workforce has its breaking point. Often, it is not the grand systemic robbery that provokes rebellion but a smaller, more personal act of indignity—a manager’s unnecessary cruelty, a sudden policy change, or a petty insult that bruises the collective ego. What ignites a strike is not necessarily the magnitude of the offense but the human response to it, the moment when subservience becomes unbearable, and the cost of rebellion pales in comparison to the cost of submission.

This phenomenon is not unique to workers, of course. History is replete with examples of revolutions sparked by the symbolic rather than the material. The French Revolution did not erupt over the totality of feudal oppression but over bread riots and whispers of noble excess. The Boston Tea Party was not a revolt against British imperialism in its entirety but a protest over a tax on a single commodity. These events seem minor in isolation, but they represent the tip of an iceberg, the moment when the submerged grievances of a people break through to the surface.

For workers, the “small incident” often carries a disproportionate weight because it crystallizes the daily humiliations of life under capitalism. A sudden demand to work an extra unpaid hour or a supervisor’s condescending remark might seem negligible compared to a wage cut or the outsourcing of jobs. Yet these small acts of disrespect often feel more personal, more immediate. They strip away the veneer of civility and expose the raw power dynamics at play. It is in these moments that workers rediscover their collective strength and solidarity, realizing that what they endure individually can be resisted collectively.

One might ask why this rediscovery doesn’t occur earlier, why workers often tolerate greater injustices while striking over smaller ones. The answer lies in the nature of power. Systemic attacks—cuts to pensions, erosion of benefits—are often framed as inevitable, part of an impersonal economic logic beyond the control of any individual. But a minor slight, a single unreasonable demand, is easily attributed to a person—a manager, an executive—whose arrogance can be targeted and confronted. Workers, like all human beings, need a tangible enemy against which to direct their anger. The small incident provides that enemy.

Furthermore, these “small” strikes are not really about the immediate issue at hand. They are about asserting agency in a system designed to deny it. They are about sending a message, not just to management but to oneself and one’s colleagues, that the line of dignity cannot be crossed without consequence. In striking, workers reclaim a piece of their humanity, a piece that has been chipped away by years of quiet compliance and acquiescence.

And so, what may appear as irrational is, in fact, profoundly rational. The small incident is the fulcrum upon which the lever of rebellion rests, the moment when workers decide that enough is enough. It is a reminder that human beings, no matter how subjugated, retain an innate sense of fairness and justice, a sense that can be suppressed but never extinguished.

To understand this is to understand something essential about the human condition: that we endure much, but not indefinitely; that we tolerate injustice, but only until the affront to our dignity becomes too great. Workers strike not just for better conditions but for the affirmation of their worth, their humanity. And if that spark begins with a “small” incident, so be it. The real surprise is not that they strike, but that they wait so long to do so.

Leave a comment